Why Are Florida's Sawfish Dying?

Jacqui NormanReports of critically endangered sawfish acting strange have increased in the lower Keys, Florida.

Scientists and state officials from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) are racing to uncover why dozens of smalltooth sawfish—a critically endangered species—are swimming strangely and dying in a 35-mile region of the lower Florida Keys.

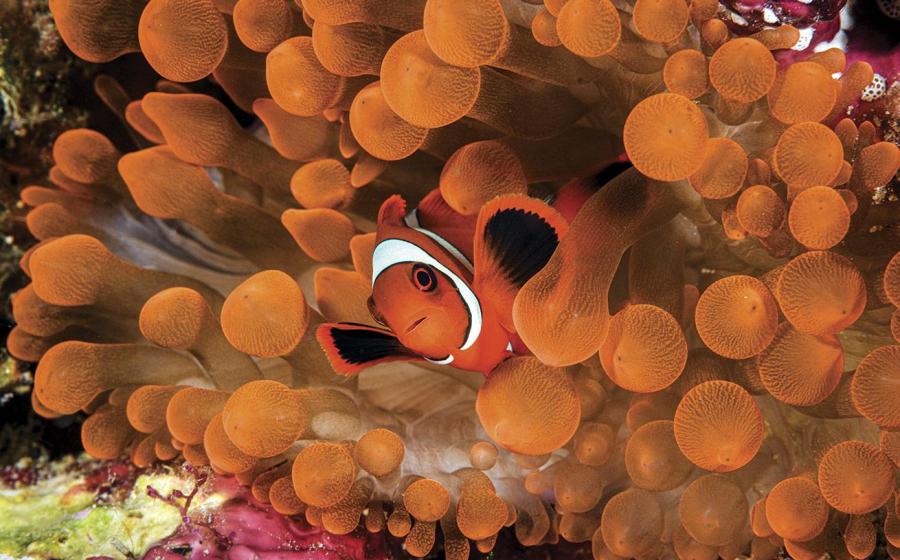

The bottom-dwelling sharks, which are technically members of the ray family, are characterized by a long flat body and an elongated nose, or rostrum, with large, sharp teeth protruding from the sides.

As of March 6 2024, 20 sawfish have died. “The concern, since it's an endangered species, is having this many die all at once,” said Dean Grubbs, associate director of research at Florida State University’s Coastal and Marine Laboratory.

Related Reading: Looking for Lost Sharks

Grubbs, who has studied sawfish since 2008 and is also a member of the NOAA Smalltooth Sawfish Recovery Team, said they are beaching themselves in shallow water, slashing their rostrums around in circles. “It’s not normal behavior,” he said.

But, the odd swimming isn’t just limited to sawfish. Since November, locals in the Florida Keys have reported fish exhibiting the spins, particularly at night when lights were shined on the fish.

To date, 30 species have exhibited these abnormal signs, including silver mullet, tarpon, permit, snook, various snapper species, goliath grouper and more, according to the Bonefish and Tarpon Trust.

A collaborative effort was launched on January 11 with scientists from multiple universities and institutes, as well as FWC and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to figure out the cause.

Joyce MilelliA sawfish in the shallow waters of the Keys.

At first, researchers wondered if it was an environmental issue, like temperature or low oxygen levels in water. “We’ve taken measurements, and they are normal,” Grubbs said. “There’s plenty of oxygen, and the water is warm enough for them.”

They are continuing to rule out other causes by testing symptomatic fish for diseases and parasites, and testing the water for traces of harmful algal blooms, like red tide. Those don’t seem to be the cause, said Michael Parsons, a marine scientist from Florida Gulf Coast University.

But what was found were high concentrations of Gambierdiscus, a type of microscopic, single-celled algae called dinoflagellates, that live on the seafloor.

Gambierdiscus species can produce a potent neurotoxin called ciguatera, which Parsons studies. Fish ingest it by eating, and the toxin becomes more powerful as it makes its way up the food chain. It can also make people sick if they eat contaminated fish.

Related Reading: Can Fish Survive in Both Fresh and Salt Water?

“We usually see 30 or 40 cells of Gambierdiscus up in the water column per liter of water,” Parsons said. The reports from FWC’s water samples revealed 1,000 cells per liter of water. “That’s actually high, because normally it lives on seagrass.”

That led Parsons and other team members to wonder if ciguatera was the cause of the fish behavior and deaths. “It wasn't red tide, it was not low oxygen, it doesn't look like it's parasites or any fish disease caused by microbes. Basically, this is our strongest lead right now, but we have no definitive answers,” Parsons said.

Right now, team members are analyzing more water samples and the tissues of the fish to look for signs of ciguatera. They’ve also necropsied the dead sawfish, and continue to collect more samples for analysis. Parsons and others have plans for more widespread sampling of fish and water in March.

“Ciguatera seems like a good lead,” Parsons said, “Either way, if we prove it or disprove it, it's going to move us forward.”

FWC encourages anyone who sees or notices abnormal fish behavior or deaths to report it. “Public reports are an essential resource to our investigation into this event,” according to a statement.

FWC staff are coordinating recovery of carcasses, which is aided by reports to the sawfish hotline ([email protected]; 844-4SAWFISH). Samples from carcasses are being sent to FWC’s Fish Health group for analysis and/or distribution to experts elsewhere.