What’s the Average Size of a Shark?

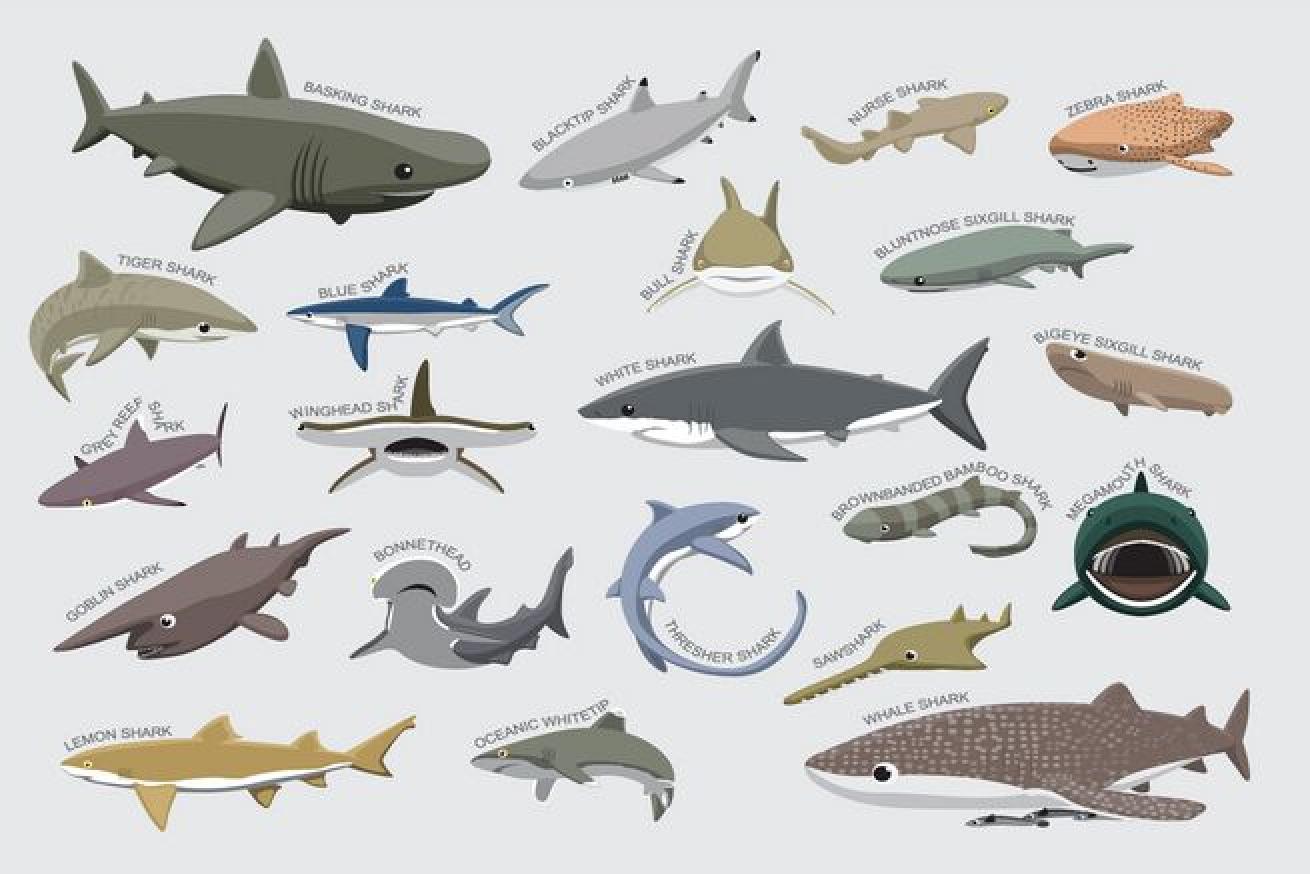

Shutterstock.com/MaquiladoraSome sharks are big, some are small, but what's the average size of them all?

Frequently Asked Question: “Everyone knows that the whale shark is the biggest shark, but what’s the average size of a shark?”

Answer: Just over four feet—127 centimeters to be exact—according to data I gathered from my well-worn copy of “Sharks of the World,” a Princeton Field Guide. This handy-dandy reference estimates the maximum size for each species, and I simply took the average (or mean) of those values. Scientists also typically record (or sometimes estimate) size at birth and size at reproductive maturity or adulthood rather than the most commonly observed size — it’s hard to get the most commonly observed size, as from the standpoint of management that’s less important than the other data mentioned here.

Related Reading: What Are the Best Schools to Study Marine Biology?

The 2005 edition of “Sharks of the World” I have in my home office is a little older, and there’s a newer still edition coming out next year. While there have likely been lots of new studies on age growth and life history of many of these species (such as this 2017 study on grey reef sharks), as well as several new species discoveries (including my favorite, the ninja Lanternshark, discovered a few years ago), my calculation includes length measurements or estimates for 449 species of sharks that were scientifically current as of when I was in college.

For your reference, “Sharks of the World” records a shark’s total length, which is the distance from the tip of a shark’s snoot to the tip of their tail if they’re stretch out in a straight line, but there are several ways to measure the length of the shark. Other measurement options include pre-caudal length, which is the distance from the tip of a shark’s snoot to the little notch right before their tail, and fork length, which is the distance from the tip of the snoot to the fork of the tail. It’s not uncommon for field researchers to record more than one of these (or even all three) because they’re useful for different things, but here I only used total length.

It’s also important to know that some species of sharks are much better studied than others. In some cases, “Sharks of the World” notes that a species has a maximum size of “at least” a certain size, indicating that’s the biggest one that’s ever been measured but there’s no reason to believe that species cannot exceed that length. Additionally, in many species of sharks the female is larger than the male (which is why the “baby shark” dance is scientifically inaccurate), so whenever there were different maximum lengths reported for male and female sharks I used the larger value for each species.

Of the 449 species in “Sharks of the World,” 371 of them have a maximum size smaller than that of the average adult male human (a little less than six feet). More than 110 max out below two feet, and the smallest shark is the dwarf lanternshark at 21 centimeters, about eight inches—though the book notes that the one specimen ever seen of the pale catshark was also 21 centimeters long.

Related Reading: Why Do Sea Turtles Return to the Same Beach?

Ask a Marine Biologist is a monthly column where Dr. David Shiffman answers your questions about the underwater world. Topics are chosen from reader-submitted queries as well as data from common internet searches. If you have a question you’d like answered in a future Ask a Marine Biologist column, or if you have a question about the answer given in this column, email Shiffman at [email protected] with subject line “Ask a marine biologist.”

Courtesy David ShiffmanDr. David Shiffman

Dr. David Shiffman is a marine conservation biologist specializing in the ecology and conservation of sharks. An award-winning public science educator, David has spoken to thousands of people around the world about marine biology and conservation and has bylines with the Washington Post, Scientific American, New Scientist, Gizmodo and more. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, where he’s always happy to answer any questions about sharks.

The views expressed in this article are those of David Shiffman, and not necessarily the views of Sport Diver or Scuba Diving magazines.