Izu Peninsula

The coastal waters of Japan belong almost exclusively to the fishermen who supply the Japanese population with most of the protein in its diet. Reluctantly, the fishermen share a small portion of their realm with the many scuba divers from Tokyo who descend upon coastal fishing villages every weekend. For logistical and other reasons, very few gai-jin (foreigners) have dived in temperate Japanese waters.

Jogashima

I feel fortunate, then, to be preparing to dive with dive buddy and fellow photographer Chris Bangs on Jogashima, a tiny island off the Miura Peninsula about 100 miles south of Tokyo. At the dive center, we set up our cameras and unpack our dive gear, then board a traditional wooden fishing boat. The boat is clean, and the wooden benches are more than adequate for the 15-minute ride to our first dive site.

Visibility in the 56-degree water is 70 to 80 feet. There are pastel-colored soft corals several feet in height attached to rocky outcrops and boulders. I notice wrasses, butterflyfish and other seemingly tropical species in this cold water, but they are subtly different from Melanesian and Micronesian forms that I have come to know well.

I photograph a tiny fringehead pikeblenny peeking out from its hole. Divemaster Rika Kura points out a much larger hole-dweller nearby, a conger eel whose body seems as thick as my thigh. Chris finds an intricately patterned pinecone fish; it is deep within a crevice, but will emerge after dark with light organs flashing, powered by bioluminescent bacteria.

Every place I look, I see new photographic subjects. A dense carpet of multicolored, iridescent algae covers the seafloor. A pair of arrowcrabs cavort in a black coral tree. A large moray eel sits perfectly still out in the open with mouth agape, allowing me to photograph its tonsils from a few inches away. A striped filefish swims slowly past, pausing just long enough in front of a multicolored sea fan for a quick portrait or two.

Yawatano

A couple of days later, we drive farther south to Futo Point, in Yawatano on the Izu Peninsula. Vehicles are not permitted near the entry point, so we don full gear and carry cameras the rest of the way. A concrete ramp allows fairly easy entry for shore diving. Chris says that on summer weekends there are so many divers in line here that it may require a wait of 30 minutes or more to enter the water.

Once we are below, our divemaster Kei quickly proves his mettle. Within minutes he spots an all-but-invisible quarter-inch cowrie on a small gorgonian; tiny branched papillae on the cowrie's mantle perfectly mimic the gorgonian coral polyps. Nearby I discover a striking red seahorse with long, fleshy appendages that resemble tree branches.

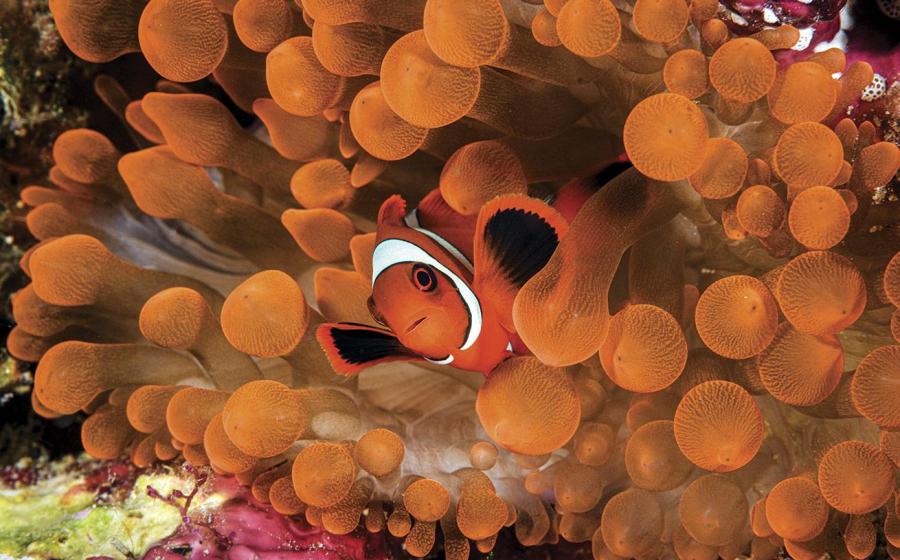

The second dive is even better. I find an exotic dragon moray in its den; it is colored in gold and white, with antenna-like projections protruding from its narrow head. Soon we spot a second one out in the open, and I'm surprised to discover its small head sitting at the end of a thick, four-foot-long body. On our way back, we swim over a seemingly endless aggregation of bulb-tentacled sea anemones, resplendent in opalescent green and yellow, some of which host pairs of Clark's anemonefish.

The deeper waters off Yawatano are clear, and the soft corals seem exceptionally large and healthy. We see a multicolored venomous sea urchin complete with resident zebra crab, a large yellow starfish with commensal shrimp, and a brilliantly colored tiger cowrie grazing on a gorgonian coral colony. A large stingray rests on the sandy bottom at 100 feet, nestled between deep purple cerianthid anemones. A pale orange slipper lobster with a zigzag carapace seems unperturbed by our presence. Our guide points out two frogfish sharing a rocky ledge; one is brilliant red but appears dark brown at this depth, while the other is clothed in drab gray.

Osezaki

Across the Izu Peninsula is the small resort town of Osezaki, within sight of the summit of snow-covered Mt. Fuji, which rises more than 12,000 feet above sea level.

Planning to make two shore dives from the western side of Osezaki, we place our dive gear and cameras in wooden carts and push the carts almost a mile over uneven terrain. The sand is dark with volcanic ash, a reminder that Fuji was once an active volcano--having last erupted in 1707. The underwater visibility here is also quite good. At a depth of 110 feet, we enter a thick forest of mixed gorgonian, soft and wire corals. A golden hawkfish perches majestically on a red sea fan. A snow-white devil scorpionfish, usually well-camouflaged, is blatantly visible against the almost black sand. I photograph an enormous purple sea fan, partly covered with small colonial anemones. Everywhere there are schools of cardinalfish and cherry-red anthias. Later, while completing a decompression stop in shallow water, I observe dozens of colorful hingebeak shrimp sharing a rocky crevice with a young dragon moray.

Later, we find a long-ago discarded soft-drink can, encrusted with algae and broyzoans. A pair of tiny yellow gobies peers out from the opening, and I wonder if this is the inevitable future for all creatures of the sea; learn to live with human-generated garbage, or perish. I shoot off the last of my film, and reluctantly turn back toward shore.

Travel Tips

-

If at all possible, make arrangements in advance to travel and dive with someone who is bilingual; unlike major Japanese tourist cities, English is not widely spoken at Izu.

-

Avoid summer or autumn weekends and Japanese holidays, when popular dive sites are extremely crowded.

-

For additional information on dive operators, accommodations and prices, check out these web sites:

www.divejapan.com/dive_service.htm

www.dive-h2o.com/dive_japan_en2-z2/dive_japan_en2-z2.html

Dive In: Japan's Izu Peninsula

Getting There

From Tokyo, you can get to towns at the base of the Izu Peninsula by train in under two hours, and from there use local train lines or a taxi to reach your final destination. Another method is to sign up for a weekend tour with a Tokyo dive shop that provides a van to transport divers and gear.

Best Time to Visit

Diving at Izu is done year-round, but conditions are highly variable. In summer and early autumn, water temperature may reach the low 80s, underwater visibility is typically 15 to 30 feet and popular dive sites can be extremely crowded. In winter, water temperature may drop to the mid-50s, visibility increases to 40 to 80 feet (even more at offshore islands), but the weather can be less reliable. Dry suits are highly recommended for winter diving at Izu.

Documents

You must have a passport; visas are not required for U.S. citizens staying less than 90 days.

Electricity

100v AC, 50Hz; U.S.-style plugs. Most American-made electrical devices will function reasonably well without need for a converter.

Money Matters

At press time the U.S. dollar was worth about 110 Japanese yen. Credit cards are widely used in major cities, but for Izu you will need cash. Change money at the airport or in Tokyo, and bring lots of it--both diving and accommodations are quite expensive. A two-tank boat dive can be $125 or more.

The coastal waters of Japan belong almost exclusively to the fishermen who supply the Japanese population with most of the protein in its diet. Reluctantly, the fishermen share a small portion of their realm with the many scuba divers from Tokyo who descend upon coastal fishing villages every weekend. For logistical and other reasons, very few gai-jin (foreigners) have dived in temperate Japanese waters.

Jogashima

I feel fortunate, then, to be preparing to dive with dive buddy and fellow photographer Chris Bangs on Jogashima, a tiny island off the Miura Peninsula about 100 miles south of Tokyo. At the dive center, we set up our cameras and unpack our dive gear, then board a traditional wooden fishing boat. The boat is clean, and the wooden benches are more than adequate for the 15-minute ride to our first dive site.

Visibility in the 56-degree water is 70 to 80 feet. There are pastel-colored soft corals several feet in height attached to rocky outcrops and boulders. I notice wrasses, butterflyfish and other seemingly tropical species in this cold water, but they are subtly different from Melanesian and Micronesian forms that I have come to know well.

I photograph a tiny fringehead pikeblenny peeking out from its hole. Divemaster Rika Kura points out a much larger hole-dweller nearby, a conger eel whose body seems as thick as my thigh. Chris finds an intricately patterned pinecone fish; it is deep within a crevice, but will emerge after dark with light organs flashing, powered by bioluminescent bacteria.

Every place I look, I see new photographic subjects. A dense carpet of multicolored, iridescent algae covers the seafloor. A pair of arrowcrabs cavort in a black coral tree. A large moray eel sits perfectly still out in the open with mouth agape, allowing me to photograph its tonsils from a few inches away. A striped filefish swims slowly past, pausing just long enough in front of a multicolored sea fan for a quick portrait or two.

Yawatano

A couple of days later, we drive farther south to Futo Point, in Yawatano on the Izu Peninsula. Vehicles are not permitted near the entry point, so we don full gear and carry cameras the rest of the way. A concrete ramp allows fairly easy entry for shore diving. Chris says that on summer weekends there are so many divers in line here that it may require a wait of 30 minutes or more to enter the water.

Once we are below, our divemaster Kei quickly proves his mettle. Within minutes he spots an all-but-invisible quarter-inch cowrie on a small gorgonian; tiny branched papillae on the cowrie's mantle perfectly mimic the gorgonian coral polyps. Nearby I discover a striking red seahorse with long, fleshy appendages that resemble tree branches.

The second dive is even better. I find an exotic dragon moray in its den; it is colored in gold and white, with antenna-like projections protruding from its narrow head. Soon we spot a second one out in the open, and I'm surprised to discover its small head sitting at the end of a thick, four-foot-long body. On our way back, we swim over a seemingly endless aggregation of bulb-tentacled sea anemones, resplendent in opalescent green and yellow, some of which host pairs of Clark's anemonefish.

The deeper waters off Yawatano are clear, and the soft corals seem exceptionally large and healthy. We see a multicolored venomous sea urchin complete with resident zebra crab, a large yellow starfish with commensal shrimp, and a brilliantly colored tiger cowrie grazing on a gorgonian coral colony. A large stingray rests on the sandy bottom at 100 feet, nestled between deep purple cerianthid anemones. A pale orange slipper lobster with a zigzag carapace seems unperturbed by our presence. Our guide points out two frogfish sharing a rocky ledge; one is brilliant red but appears dark brown at this depth, while the other is clothed in drab gray.

Osezaki

Across the Izu Peninsula is the small resort town of Osezaki, within sight of the summit of snow-covered Mt. Fuji, which rises more than 12,000 feet above sea level.

Planning to make two shore dives from the western side of Osezaki, we place our dive gear and cameras in wooden carts and push the carts almost a mile over uneven terrain. The sand is dark with volcanic ash, a reminder that Fuji was once an active volcano--having last erupted in 1707. The underwater visibility here is also quite good. At a depth of 110 feet, we enter a thick forest of mixed gorgonian, soft and wire corals. A golden hawkfish perches majestically on a red sea fan. A snow-white devil scorpionfish, usually well-camouflaged, is blatantly visible against the almost black sand. I photograph an enormous purple sea fan, partly covered with small colonial anemones. Everywhere there are schools of cardinalfish and cherry-red anthias. Later, while completing a decompression stop in shallow water, I observe dozens of colorful hingebeak shrimp sharing a rocky crevice with a young dragon moray.

Later, we find a long-ago discarded soft-drink can, encrusted with algae and broyzoans. A pair of tiny yellow gobies peers out from the opening, and I wonder if this is the inevitable future for all creatures of the sea; learn to live with human-generated garbage, or perish. I shoot off the last of my film, and reluctantly turn back toward shore.

Travel Tips

If at all possible, make arrangements in advance to travel and dive with someone who is bilingual; unlike major Japanese tourist cities, English is not widely spoken at Izu.

Avoid summer or autumn weekends and Japanese holidays, when popular dive sites are extremely crowded.

For additional information on dive operators, accommodations and prices, check out these web sites:

www.divejapan.com/dive_service.htm

www.dive-h2o.com/dive_japan_en2-z2/dive_japan_en2-z2.html

Dive In: Japan's Izu Peninsula

Getting There

From Tokyo, you can get to towns at the base of the Izu Peninsula by train in under two hours, and from there use local train lines or a taxi to reach your final destination. Another method is to sign up for a weekend tour with a Tokyo dive shop that provides a van to transport divers and gear.

Best Time to Visit

Diving at Izu is done year-round, but conditions are highly variable. In summer and early autumn, water temperature may reach the low 80s, underwater visibility is typically 15 to 30 feet and popular dive sites can be extremely crowded. In winter, water temperature may drop to the mid-50s, visibility increases to 40 to 80 feet (even more at offshore islands), but the weather can be less reliable. Dry suits are highly recommended for winter diving at Izu.

Documents

You must have a passport; visas are not required for U.S. citizens staying less than 90 days.

Electricity

100v AC, 50Hz; U.S.-style plugs. Most American-made electrical devices will function reasonably well without need for a converter.

Money Matters

At press time the U.S. dollar was worth about 110 Japanese yen. Credit cards are widely used in major cities, but for Izu you will need cash. Change money at the airport or in Tokyo, and bring lots of it--both diving and accommodations are quite expensive. A two-tank boat dive can be $125 or more.