Diving the Kittiwake: Making of a Metalhead

Diving the Kittiwake: Making of a Metalhead

Elly Wray

Sunken ships have gravity. There’s something elementally compelling about a vessel submerged in the deep. It draws us uncontrollably, turning us back into curious youngsters, plunging us into the unknown, where we’re sometimes too excited to consider precautions — or consequences. Enticed by the promise of adventure and mysteries revealed, I didn’t wait long in my dive career to drop on wrecks that were big, deep and, admittedly, beyond my level of training. Then I decided to do it the right way: Learn the proper techniques, master the required safety gear, and become a certified wreck diver. Grand Cayman’s Kittiwake, a purpose-sunk artificial reef prepared for divers by divers, would prove the perfect training ground. I’ve dived dozens of more-challenging wrecks. But I had no idea how badly I was doing it.

Preparation:

A proper wreck dive begins on dry land, long before a buddy team ever hits the water. Thorough historical research, dive-profile planning and equipment preparation create the foundation for a successful — and safe — artificial reef adventure. While it’s totally acceptable to place yourself in the capable hands of a qualified dive professional to guide you through the experience, every diver should strive for self-reliance, especially in such a potentially hazardous environment.

My re-education from enthusiastic dilettante to bona-fide wreck diver starts in a classroom at Divetech on the breezy northwest point of Grand Cayman. The long-standing operation at the Cobalt Coast Resort & Suites offers a broad range of training, from Discover Scuba Diving for the uninitiated to advanced technical and rebreather diving for the top of the pyramid. My instructor, Nick Lawton, a lanky London native with an eight-year tenure at Divetech, is a fan of artificial reefs. I like him already.

“Wrecks turn me back into a 14-year-old boy,” he says with an impish grin. “But a healthy dose of respect for the process of diving an artificial reef is very important.”

The course work for the PADI Wreck Diver Specialty is a mix of training videos, manual study, and student-instructor discussion that covers the theories, techniques, and protocols that will ensure the safest and most responsible experience possible. Great emphasis is placed on the potential hazards of this special underwater environment: injury from sharp metal, splintering wood, abrasive organisms or unexploded ammunition, entanglement in ropes, monofilament or a diver’s own guideline, and entrapment caused by the fall of unstable structures or suction created by surge in enclosed spaces.

The ominous soundtrack of the video I’m watching is very appropriate as I learn about the dangers of penetrating an overhead environment — getting lost in the three-dimensional maze of a ship’s guts, losing visibility in a silt-out, or finding no easy escape in an emergency. The realities of wreck diving that I once brazenly shrugged off are gaining serious weight in my mind. Thankfully, the rest of the course teaches me how to manage these risks in a responsible way, through careful evaluation, mapping and navigation, proper use of a reel and guideline, maintaining good buoyancy, and much more.

When it’s time to test my course-manual knowledge retention, I feel more prepared and confident than ever before — and the best part is yet to come. The three-day course culminates with four checkout dives on an artificial reef, where divers first survey and then penetrate the ship. It’s my good fortune to have the Kittiwake as a proving ground.

The former United States Navy submarine rescue ship was scuttled in early 2011 after a long and careful preparation that involved not only a thorough cleaning, but also a thoughtful process of “redesigning,” which removed hatches, floors, bulkheads and other original amenities to create more access for divers. It’s so open and full of light inside that penetration seems way too easy. That is until I put my new wreck training into action.

Performing the skills necessary to pass the class is no mindless joy ride, I’ll soon discover.

Survey:

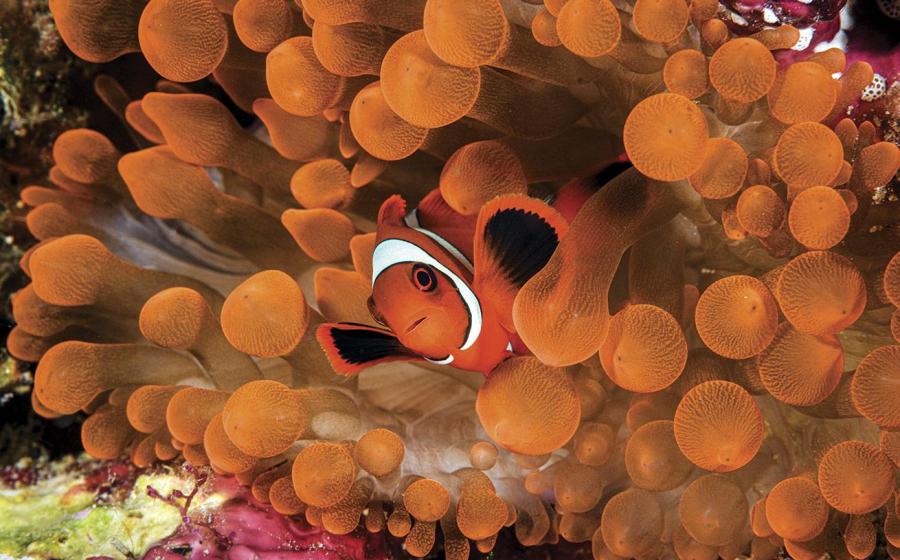

The outside of a wreck is a horrible tease. For me, the real excitement is exploring inside. Swimming around the exterior of a shipwreck is something most any open-water diver can do safely. Sure, the visuals are cool, and the vast majority of marine-life encounters take place here — but the secrets lie within.

However passive, getting a comprehensive overview of a ship and drawing a detailed map of useful landmarks, potential hazards, and entry and exit points is a fundamental part of every safe wreck exploration — and the first part of the Wreck Diver checkout dives.

Finally in the water, Lawton and I kick toward our target from the southeast, following one of the massive anchor chains until the ship appears, KITTIWAKE emblazoned on the stern. It’s a bright, sunny Tuesday with clear 80-foot visibility and, miraculously, we have the site all to ourselves. On my slate, I sketch a pair of rudimentary hull outlines on one side and the beginning of a rough profile on the other. Starting with the massive propeller, I begin the process of filling in the blank spaces on my diagram as we tour the wreck.

The Kittiwake’s bounty of compelling structural features — which are spread over 251 feet of length and five decks — begins to crowd my drawing. From the massive crane boom and support towers at the stern to a vertical saturation tank towering above the port gunwale, giant winches at midship, massive float tanks welded to either side, and a crow’s nest at the bow complete with water canon, the folks who prepared this artificial reef preserved as much of the ship’s submarine-rescuing heritage as possible, to the great benefit of visiting divers. And its favorable location, on a shallow, approximately 60-foot-deep sand flat next door to the island’s flush fringing reef system, means long bottom times to explore and lots of marine species spillover. Consistently warm water doesn’t hurt the site’s appeal either.

Finning along the port side, I spy a giant southern stingray cruising between the wreck and the neighboring Sand Chute site. Large-diameter holes cut into the hull at what was once the water line offer hints at the treasures inside. As I rise up over the bow to inspect a large winch, a brave sergeant major pecks at my head, agitated that I’ve come close to its eggs. We continue our tour around the starboard side, wind up through the boat-deck structure and have a peek into the bridge, where the ship’s wheel and compass have been left intact. Hovering around the midship tower during our safety stop, we watch a school of sturdy silver jacks flash by in the sunlight. I can see the entire ship from this vantage point, imagining what I’ll find inside. That, unfortunately, will have to wait until tomorrow.

Penetration:

The target was selected well in advance. Planning the first of our two penetration checkout dives, Lawton decides we will enter the Kittiwake through a large circular hole that’s been cut into the port side, pass through the adjacent bulkhead to a second chamber, drop down into the engine room through a massive cutout in the floor, continue forward toward the bow through another hole in the bulkhead, turn around and retreat. I’ll lead the dive, tying off our guideline and pointing out potential hazards along the way before reeling it all back up on the return trip. And Lawton will judge my every move. (Gulp.)

“I will chuck some really obnoxious curve balls at you,” he jokes to break my apparently noticeable tension as we gear up on board the Atatude. But then adds a note of encouragement. “It all comes down to planning your dive and diving your plan,” he says.

That morning, on our first dive of the day, I spend nearly an hour practicing the process of laying guidelines all over the exterior of the ship. Under Lawton’s direction, I navigate through tight spaces, down narrow gangways and along multiple decks, all while being careful to tie sturdy knots and keep my fins off the bottom. Swimming down an outside stairway without touching metal or getting tangled in the neon-orange line proved the toughest challenge, and I catch myself laughing through my second stage at the struggle — although I am glad to have a trial run before the serious business of entering an overhead environment.

But go time has arrived.

Hovering outside the 4-foot-wide opening, I double-check that my kit is streamlined: dive reel and primary light in hand, secondary light and slate with boat sketch secured to my BC, and knife strapped tightly to my calf. I take a calming breath before pulling myself inside, Lawton following about a body length behind me. The room is impressively large, completely empty and brightly lit from other holes on the starboard side. I survey the space to plan where I’ll tie the line at intervals of 10 feet or so and proceed forward.

The line-laying process — and the Wreck Diver training in general — has changed my focus noticeably. Rather than being all-consumed with discovering the interesting sights and hidden critters inside the wreck, I’m far more concerned about safety, and my situational awareness is on point. As we drop through an L-shaped hole and into the cavernous engine room, flooded with light from high above, my appreciation for the Kittiwake is growing exponentially. This truly is a wreck diver’s wreck.

Our second penetration route takes us through the main deck via the galley, through a room that’s open all the way to the surface through the smoke stack, and out into open water through the head, where mirrors lining the wall cause a double-take at my reflection. Bottom time running out, we’ve explored only a fraction of this ship, and I’m already planning my next dives on the wreck as we off-gas at 15 feet.

Climbing back on the boat, I find it hard not to let out a loud hoot of triumph. But I’m not actually sure that I’ve achieved success.

“Did I pass?” I ask, hopefully.

“Congratulations,” Lawton responds with outstretched handshake.

Reflecting on the experience, I’m certain that this training has made me a more confident — and more important, safer — diver. And I’m sure it will benefit my future underwater adventures in countless ways I’ve yet to discover. Not to mention it has opened the door to dozens of new wrecks on my ever-growing hit list.

3 Artificial Reefs of the Cayman Islands:

1 M/V Capt. Keith Tibbetts: This massive 330-foot Russian frigate, scuttled in 110 feet of water off Cayman Brac in 1996, was twisted in half by Hurricane Ivan, creating a multilevel dive with gun turrets and heaps of structure and penetration routes.

2 Doc Paulson: Sunk in 1981 off Grand Cayman’s Seven Mile Beach, this 70-foot ship is a shallow wreck dive with easy penetration and lots of marine life, from seasonal silversides to schooling jacks.

3 Cayman Mariner: Resting at 55 feet next to an awesome wall dive off Cayman Brac, the 65-foot wreck sunk in 1986 is a magnet for green sea turtles, hunting barracuda and much more.

Need to Know:

When to Go: Grand Cayman is a year-round dive destination. The rainy season runs June through October.

Diving Conditions: Water temps range from the high 70s in winter to the low 80s in summer. Average visibility is 90 feet but varies with weather, tides, and spring and fall plankton blooms.

Operator: Dive Cayman (divecayman.ky) — a Web portal operated by the Cayman Islands Department of Tourism — offers a searchable database of dive operators on Grand Cayman, Little Cayman and Cayman Brac.

Price Tag: Divetech Ltd. (divetech.com) at the Cobalt Coast Resort & Suites (cobaltcoast.com) offers the PADI Wreck Diver Specialty Course, including four boat dives on the Kittiwake and $10 daily park fee, for $450. All inclusive lodging/dining packages at the oceanfront resort start at $1,365.

Elly Wray

Sunken ships have gravity. There’s something elementally compelling about a vessel submerged in the deep. It draws us uncontrollably, turning us back into curious youngsters, plunging us into the unknown, where we’re sometimes too excited to consider precautions — or consequences. Enticed by the promise of adventure and mysteries revealed, I didn’t wait long in my dive career to drop on wrecks that were big, deep and, admittedly, beyond my level of training. Then I decided to do it the right way: Learn the proper techniques, master the required safety gear, and become a certified wreck diver. Grand Cayman’s Kittiwake, a purpose-sunk artificial reef prepared for divers by divers, would prove the perfect training ground. I’ve dived dozens of more-challenging wrecks. But I had no idea how badly I was doing it.

Preparation:

A proper wreck dive begins on dry land, long before a buddy team ever hits the water. Thorough historical research, dive-profile planning and equipment preparation create the foundation for a successful — and safe — artificial reef adventure. While it’s totally acceptable to place yourself in the capable hands of a qualified dive professional to guide you through the experience, every diver should strive for self-reliance, especially in such a potentially hazardous environment.

My re-education from enthusiastic dilettante to bona-fide wreck diver starts in a classroom at Divetech on the breezy northwest point of Grand Cayman. The long-standing operation at the Cobalt Coast Resort & Suites offers a broad range of training, from Discover Scuba Diving for the uninitiated to advanced technical and rebreather diving for the top of the pyramid. My instructor, Nick Lawton, a lanky London native with an eight-year tenure at Divetech, is a fan of artificial reefs. I like him already.

“Wrecks turn me back into a 14-year-old boy,” he says with an impish grin. “But a healthy dose of respect for the process of diving an artificial reef is very important.”

The course work for the PADI Wreck Diver Specialty is a mix of training videos, manual study, and student-instructor discussion that covers the theories, techniques, and protocols that will ensure the safest and most responsible experience possible. Great emphasis is placed on the potential hazards of this special underwater environment: injury from sharp metal, splintering wood, abrasive organisms or unexploded ammunition, entanglement in ropes, monofilament or a diver’s own guideline, and entrapment caused by the fall of unstable structures or suction created by surge in enclosed spaces.

The ominous soundtrack of the video I’m watching is very appropriate as I learn about the dangers of penetrating an overhead environment — getting lost in the three-dimensional maze of a ship’s guts, losing visibility in a silt-out, or finding no easy escape in an emergency. The realities of wreck diving that I once brazenly shrugged off are gaining serious weight in my mind. Thankfully, the rest of the course teaches me how to manage these risks in a responsible way, through careful evaluation, mapping and navigation, proper use of a reel and guideline, maintaining good buoyancy, and much more.

When it’s time to test my course-manual knowledge retention, I feel more prepared and confident than ever before — and the best part is yet to come. The three-day course culminates with four checkout dives on an artificial reef, where divers first survey and then penetrate the ship. It’s my good fortune to have the Kittiwake as a proving ground.

The former United States Navy submarine rescue ship was scuttled in early 2011 after a long and careful preparation that involved not only a thorough cleaning, but also a thoughtful process of “redesigning,” which removed hatches, floors, bulkheads and other original amenities to create more access for divers. It’s so open and full of light inside that penetration seems way too easy. That is until I put my new wreck training into action.

Performing the skills necessary to pass the class is no mindless joy ride, I’ll soon discover.

Survey:

The outside of a wreck is a horrible tease. For me, the real excitement is exploring inside. Swimming around the exterior of a shipwreck is something most any open-water diver can do safely. Sure, the visuals are cool, and the vast majority of marine-life encounters take place here — but the secrets lie within.

However passive, getting a comprehensive overview of a ship and drawing a detailed map of useful landmarks, potential hazards, and entry and exit points is a fundamental part of every safe wreck exploration — and the first part of the Wreck Diver checkout dives.

Finally in the water, Lawton and I kick toward our target from the southeast, following one of the massive anchor chains until the ship appears, KITTIWAKE emblazoned on the stern. It’s a bright, sunny Tuesday with clear 80-foot visibility and, miraculously, we have the site all to ourselves. On my slate, I sketch a pair of rudimentary hull outlines on one side and the beginning of a rough profile on the other. Starting with the massive propeller, I begin the process of filling in the blank spaces on my diagram as we tour the wreck.

The Kittiwake’s bounty of compelling structural features — which are spread over 251 feet of length and five decks — begins to crowd my drawing. From the massive crane boom and support towers at the stern to a vertical saturation tank towering above the port gunwale, giant winches at midship, massive float tanks welded to either side, and a crow’s nest at the bow complete with water canon, the folks who prepared this artificial reef preserved as much of the ship’s submarine-rescuing heritage as possible, to the great benefit of visiting divers. And its favorable location, on a shallow, approximately 60-foot-deep sand flat next door to the island’s flush fringing reef system, means long bottom times to explore and lots of marine species spillover. Consistently warm water doesn’t hurt the site’s appeal either.

Finning along the port side, I spy a giant southern stingray cruising between the wreck and the neighboring Sand Chute site. Large-diameter holes cut into the hull at what was once the water line offer hints at the treasures inside. As I rise up over the bow to inspect a large winch, a brave sergeant major pecks at my head, agitated that I’ve come close to its eggs. We continue our tour around the starboard side, wind up through the boat-deck structure and have a peek into the bridge, where the ship’s wheel and compass have been left intact. Hovering around the midship tower during our safety stop, we watch a school of sturdy silver jacks flash by in the sunlight. I can see the entire ship from this vantage point, imagining what I’ll find inside. That, unfortunately, will have to wait until tomorrow.

Penetration:

The target was selected well in advance. Planning the first of our two penetration checkout dives, Lawton decides we will enter the Kittiwake through a large circular hole that’s been cut into the port side, pass through the adjacent bulkhead to a second chamber, drop down into the engine room through a massive cutout in the floor, continue forward toward the bow through another hole in the bulkhead, turn around and retreat. I’ll lead the dive, tying off our guideline and pointing out potential hazards along the way before reeling it all back up on the return trip. And Lawton will judge my every move. (Gulp.)

“I will chuck some really obnoxious curve balls at you,” he jokes to break my apparently noticeable tension as we gear up on board the Atatude. But then adds a note of encouragement. “It all comes down to planning your dive and diving your plan,” he says.

That morning, on our first dive of the day, I spend nearly an hour practicing the process of laying guidelines all over the exterior of the ship. Under Lawton’s direction, I navigate through tight spaces, down narrow gangways and along multiple decks, all while being careful to tie sturdy knots and keep my fins off the bottom. Swimming down an outside stairway without touching metal or getting tangled in the neon-orange line proved the toughest challenge, and I catch myself laughing through my second stage at the struggle — although I am glad to have a trial run before the serious business of entering an overhead environment.

But go time has arrived.

Hovering outside the 4-foot-wide opening, I double-check that my kit is streamlined: dive reel and primary light in hand, secondary light and slate with boat sketch secured to my BC, and knife strapped tightly to my calf. I take a calming breath before pulling myself inside, Lawton following about a body length behind me. The room is impressively large, completely empty and brightly lit from other holes on the starboard side. I survey the space to plan where I’ll tie the line at intervals of 10 feet or so and proceed forward.

The line-laying process — and the Wreck Diver training in general — has changed my focus noticeably. Rather than being all-consumed with discovering the interesting sights and hidden critters inside the wreck, I’m far more concerned about safety, and my situational awareness is on point. As we drop through an L-shaped hole and into the cavernous engine room, flooded with light from high above, my appreciation for the Kittiwake is growing exponentially. This truly is a wreck diver’s wreck.

Our second penetration route takes us through the main deck via the galley, through a room that’s open all the way to the surface through the smoke stack, and out into open water through the head, where mirrors lining the wall cause a double-take at my reflection. Bottom time running out, we’ve explored only a fraction of this ship, and I’m already planning my next dives on the wreck as we off-gas at 15 feet.

Climbing back on the boat, I find it hard not to let out a loud hoot of triumph. But I’m not actually sure that I’ve achieved success.

“Did I pass?” I ask, hopefully.

“Congratulations,” Lawton responds with outstretched handshake.

Reflecting on the experience, I’m certain that this training has made me a more confident — and more important, safer — diver. And I’m sure it will benefit my future underwater adventures in countless ways I’ve yet to discover. Not to mention it has opened the door to dozens of new wrecks on my ever-growing hit list.

3 Artificial Reefs of the Cayman Islands:

1 M/V Capt. Keith Tibbetts: This massive 330-foot Russian frigate, scuttled in 110 feet of water off Cayman Brac in 1996, was twisted in half by Hurricane Ivan, creating a multilevel dive with gun turrets and heaps of structure and penetration routes.

2 Doc Paulson: Sunk in 1981 off Grand Cayman’s Seven Mile Beach, this 70-foot ship is a shallow wreck dive with easy penetration and lots of marine life, from seasonal silversides to schooling jacks.

3 Cayman Mariner: Resting at 55 feet next to an awesome wall dive off Cayman Brac, the 65-foot wreck sunk in 1986 is a magnet for green sea turtles, hunting barracuda and much more.

Need to Know:

When to Go: Grand Cayman is a year-round dive destination. The rainy season runs June through October.

Diving Conditions: Water temps range from the high 70s in winter to the low 80s in summer. Average visibility is 90 feet but varies with weather, tides, and spring and fall plankton blooms.

Operator: Dive Cayman (divecayman.ky) — a Web portal operated by the Cayman Islands Department of Tourism — offers a searchable database of dive operators on Grand Cayman, Little Cayman and Cayman Brac.

Price Tag: Divetech Ltd. (divetech.com) at the Cobalt Coast Resort & Suites (cobaltcoast.com) offers the PADI Wreck Diver Specialty Course, including four boat dives on the Kittiwake and $10 daily park fee, for $450. All inclusive lodging/dining packages at the oceanfront resort start at $1,365.