Spider Crabs, Squids and More: 5 Fascinating Giants of the Ocean

Franco Banfi/NPL/Minden PicturesGiant squid: At 43 feet, it can grow to be the length of a school bus.

The ocean is full of giants. The 10 heaviest species on Earth are all cetaceans, and the blue whale is the largest known animal ever to live. Size is relative, however, when it comes to gigantism in the ocean — a phenomenon that includes species that aren’t necessarily gargantuan in the way a blue whale is, but have nevertheless developed to be much larger than others within their own family. This includes animals that live in snorkeling depths as well as species that dwell in some of the ocean’s deepest reaches.

“We define the deep sea as everything below about 600 feet, because there is no photosynthesis below that depth,” explains Paul Yancey, a marine animal physiologist and professor of biology at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington. “But the deep sea goes all the way down to the bottoms of the trenches, reaching a maximum of about 36,000 feet in the Mariana Trench.”

And the most notorious example of deep-sea gigantism is an animal that likely every dedicated Facebook user has seen in one viral post or another. Who can forget that recent video from South Africa of a giant squid whose tentacles rise from underwater and slowly slink around a young man’s paddleboard?

Related Reading: Discovering Patagonia's Winged Comb Jelly

David Doubilet/National Geographic CreativeJapanese spider crab: At 12 feet, its leg span can match the length of a kayak.

Indeed, the giant squid is a species apart from the animal you might snack on as calamari. For starters, giant squid live between 1,000 and 2,000 feet deep, while their smaller cousins, Caribbean reef squid, prefer the shallow inshore reefs of Florida and the Bahamas. And while they have the same basic body parts of other squid — including two eyes, eight arms, a beak and a siphon — giant squid also have some truly bizarre adaptations to give them a Darwinian advantage in the never-ending quest to stay alive in the harsh conditions of the deep sea.

“Giant squid have serrated suckers for grasping prey, and eyes the size of dinner plates. And they are also possibly cannibalistic,” says Yancey, adding that while the causes of deep-sea gigantism are largely a mystery, there are hypotheses that help explain why some giant species develop the way they do. “Bigger animals are metabolically more efficient than smaller ones. So by growing large, an animal needs less food energy per unit weight,” says Yancey, adding that poor food supply could lead to deep-sea gigantism. And scarce food in the deep reaches of the sea, he says, also means there are few predators and competitors to contend with, making for long life spans and therefore greater size for some animals.

Of course, certain deep-sea animals, such as anglerfish, have developed enhanced mechanisms for catching food (think of the clever lure that lights up, attracting prey to within striking distance of the anglerfish’s mouth). But animals that fall into the deep-sea gigantism category are so large, says Yancey, that it’s difficult for even the most efficient predators to prey on them.

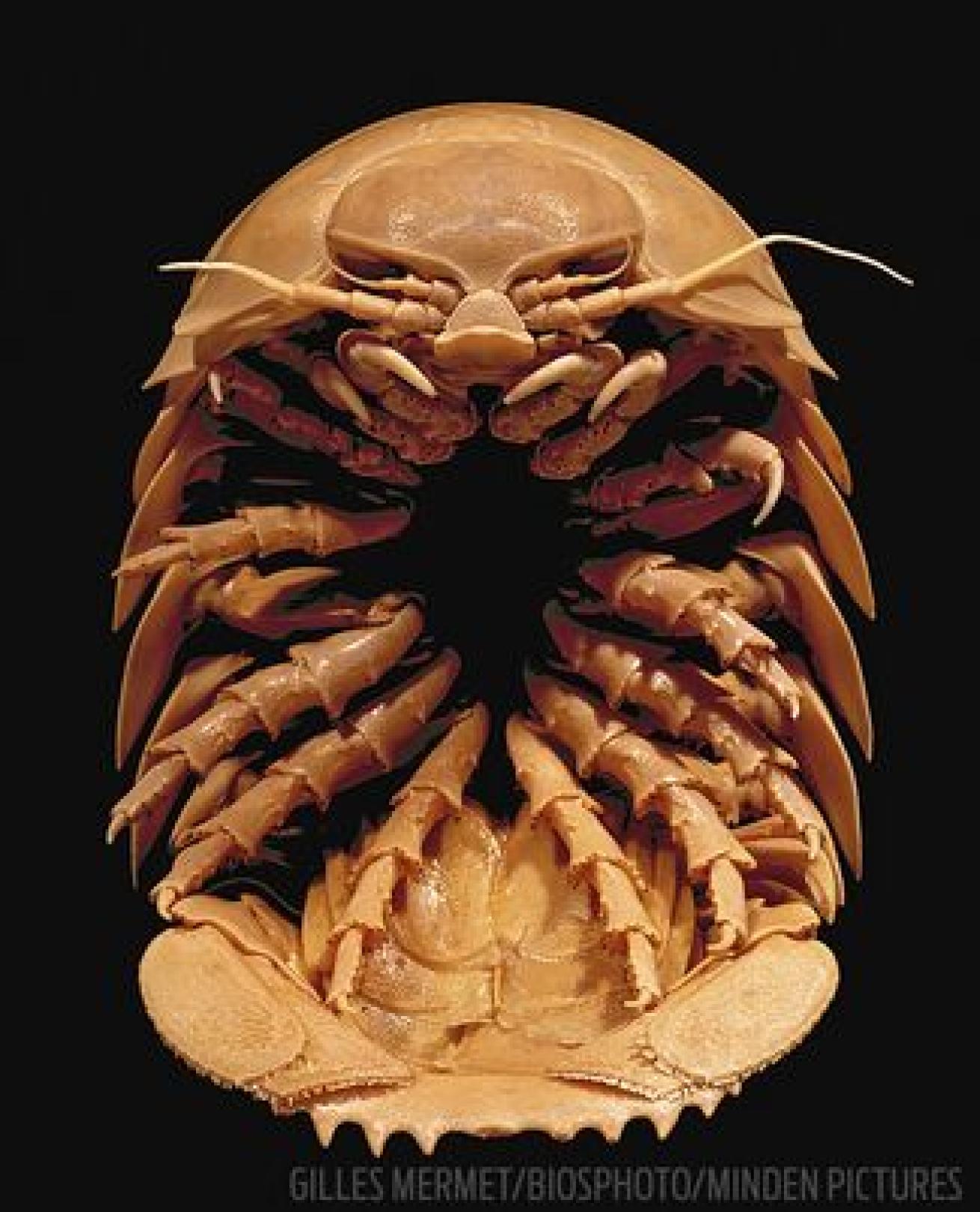

Gilles Mermet/Biosphoto/Minden PicturesGiant isopod: At 14 inches, the largest found was the size of a kitten.

Another fascinating example of deep-sea gigantism is the giant isopod — a crustacean remotely related to crabs and shrimp that looks more like a cockroach and can live below depths of 7,000 feet in the coldest reaches of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans. While regular isopods grow to about 2 inches in length, the giant species can reach nearly 10 times that length. Isopods are both scavengers and carnivores. They feed on whale carcasses on the seafloor and slow animals, such as sea cucumbers.

The Japanese spider crab is yet another deep-sea crustacean that makes the list. As the largest arthropod — a group of animals that includes not only crabs but insects and spiders too — on the planet, it is found at depths of up to 2,000 feet in the waters off Japan.

Related Reading: 7 Liveaboards to Book if You Love to Learn

Michael Patrick O'NeillLion’s mane jellyfish: At 7 feet, its bell’s diameter can be the length of a motorcycle.

The crab often dwells within vents and holes in the ocean floor and can grow up to 12 feet across (leg span). Part of the same family as decorator crabs, Inachidae, spider crabs have been seen using pieces of sponge and small anemones to camouflage their shells. And while octopuses prey on the crabs, it is humans, with their taste for crab meat, that are their biggest nemesis.

Alex MustardGiant clam: At 47 inches, its length exceeds the height of a mailbox.

Moving up in the water column, there are plenty of big-boy enigmas with shallow-water crash pads too. And if you’ve ever been snorkeling on the reefs of the South Pacific or Indian Ocean, you’ve most likely finned over a classic crustacean example: the giant clam. The largest of all mollusks, giant clams mesmerize with their iridescent mantles and can grow up to 4 feet across and weigh more than 400 pounds (that’s a lot of clam chowder).

“Just like reef-building corals, which can be collectively massive, giant clams get larger due to an efficient symbiosis with photosynthetic algae,” says Yancey. That’s science-speak to say that the animals live off of sugar and proteins in the algae that chooses to live within the safety (and sunny locale) of the clam’s tissues. And while there are plenty of South Pacific legends about giant clams snacking on slow-swimming humans, there’s no proof of a person ever falling prey to one. In fact, the clam’s snap-shut mechanism is entirely too slow to capture even the most slothlike of snorkelers or divers.

Stephen Frink Collection/AlamyPortuguese man-of-war: Maxing out at 165 feet, its tendrils can extend to the height of the Colosseum.

When it comes to massive jellyfish, the lion’s mane jellyfish — which lives mostly above depths of 66 feet in the cool waters of the Arctic, North Pacific and North Atlantic oceans — steals the show. The creature’s hundreds of tentacles can dangle down 190 feet to entrap small fish and crustaceans, and its bell can stretch 7 feet across. While it’s unknown why this species grows so large, it could be that the cold waters where it lives favor gigantism, says Yancey.

And while it has nowhere near the dimensions of the lion’s mane, one more jellyfish whose tentacles stretch into the ocean’s depths is the Portuguese man-of-war. With purplish-blue tentacles that average about 30 feet in length (but can grow as long as 165 feet), these deadly surface-skimmers possess a powerful venom and use their sails to blow across the ocean’s waters in search of prey.

It’s unknowns like these that keep scientists fascinated, and divers like us hanging on their every discovery.

“We know more about the moon and Mars than we know about our deep oceans,” says Yancey. “And learning about how life adapts to extreme conditions can give us insight into the very nature of life itself — and where else it might occur in the universe.”