How to Avoid Cave Diving Accidents and Stay Alive, According to an Expert Explorer

My workplace terrifies most people. As a cave-diving explorer, I swim alone through the claustrophobic blackness, where an error on the job may limit my chance of survival to a single breath. Even though this highly technical pursuit has claimed some of my friends, I argue that the calculated risks I assume are worth the rewards. Beyond the scientific discoveries and new maps I bring home from expeditions, cave diving has also offered opportunities for self-awareness and personal growth. Some people think I am fearless—that is not even close to accurate. The ability to acknowledge and manage a healthy level of evolutionary fear helps guide me through groundbreaking dives, and forms a framework for pursuing other significant challenges in life.

Jill Heinerth"Before every dive, I ask myself two questions: Am I capable of self-rescue? Am I willing to execute a buddy rescue?"

1. INTO THE DARKNESS

We’ve all heard divers declare, “I’ll never cave dive or go inside a wreck!” When I hear a statement like that, I know that person recognizes their limits, experience and background. They have a certain amount of emotional maturity and wisdom. It doesn’t mean that they will never be able to engage in technical diving in the future—it merely means that they are unwilling to accept the risks at this time.

I’m a little scared when I go diving, and I look at that as a good thing. Fear is a healthy emotion that lets us know we care about our future—but it also can cause emotional paralysis. The secret to survival and growth in spite of fear is finding a way to swim into life’s unknowns one small fin kick at a time. Moving toward fear means identifying risks, mitigating them through practice, and accepting responsibility for the results.

Divers often suggest that I might not want to dive with them because they are afraid. My response: “You are precisely the type of person I want to dive with.” Being fearful means you care about the outcome. Fear helps you make good choices about risk versus reward. Yet when we liberate ourselves from the contraction of fear, personal limitations and negative perceptions are minimized. We can increase our overall potential.

Learn from this

I am not suggesting that you cast away fear and carelessly run headlong into danger. As a diver, it’s important to recognize and deal with the things that cause anxiety. That means you need to take time for concentration and focus before diving—many incidents trace to causes that began long before you hit the water. To succeed, I have learned to visualize everything that can go wrong, then mentally rehearse solutions before I get wet. If, for example, I get entangled in a fishing net, I know how to find my knife and cut it away with one hand. If my buddy runs out of gas, I have just rehearsed how to share my long hose. Nervousness about a new site or partner diminishes when you engage in good physical and mental pre-dive practices. This also means that you should never stop learning. Continuing education prepares you for the next step forward; logging dives outside of classes expands your experience and currency.

2. ACKNOWLEDGE YOUR MORTALITY

In reviewing incidents, I often hear comments like, “I would never do that!” There is no logic in thinking, ‘It can’t happen to me.’ Statistics show that good people sometimes make bad decisions. The best preventive plan is to treat every dive with seriousness. Incidents can happen on the easiest of dives. We all have bad days.

Several years ago, a colleague of mine died on a rebreather dive in shallow water. I always thought of him as someone who paid proper attention to detail and safety protocols, but on the day of his death, he cut corners. During the accident investigation, his predive checklist was found nearby. The form was dated, and the first two items on the list were marked affirmative. The rest of the paperwork was unfinished. His dive was the equivalent of a pool session. He told friends he was jumping in the local lagoon to practice skills. His motive was legitimate, but for some reason, he skipped necessary safety protocols on that day. Although he could have easily stood up with his head out of the water, he drowned. He had failed to prepare his rebreather adequately, and it cost him his life.

Learn from this

Unwavering safety rituals are essential. If I have a passing thought about skipping a procedure, I force myself to think about how my husband would feel about my choice. Choose the person in your life who means the most to you and pledge to them that you will not cut corners. Before every dive, I ask myself two questions: Am I capable of self-rescue? Am I willing to execute a buddy rescue? If the answer is “no,” then I skip the dive. If the answer is “yes,” then there is no need to fear an emergency. I already know that I am capable of finishing the dive safely.

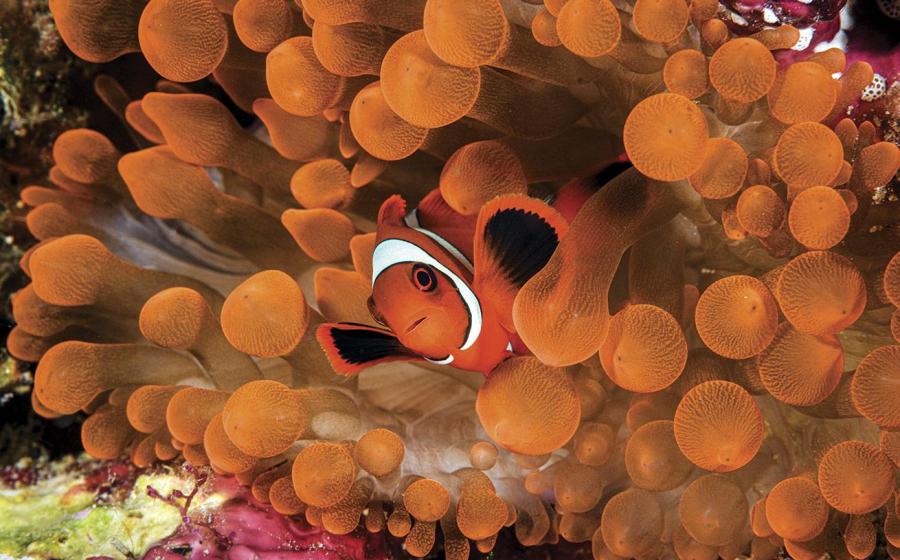

Courtesy Jill HeinerthHeinerth discovered underwater remains of a Mayan civilization and is the first person to dive into an Antarctic iceberg.

3. BREATHE DEEP

Fear is a basic human defense mechanism. Our primal selves are programmed with responses intended to keep us alive. When we find ourselves in danger, our bodies respond with fight or flight. Unfortunately, neither of those options serves us well underwater. In the face of danger, it can be tempting to bolt to the surface, but that could get you injured or killed. When I am trapped in a blinding whiteout and have lost the safety line in a cave, it’s easy to panic. My primitive brain wants to take over, seizing control of my heart and lungs. But I have learned to switch off that instinct by taking slow, deep breaths. In controlling my breathing and heart rate, I can post ponecrippling emotions and focus on the next correct decision. With practice, I can remain calm, inhaling thoughtfulness and pragmatism that help me take careful steps to find the lost guide line and, ultimately, safety.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because it’s the most basic advice from your entry-level scuba class. PADI’s mantra is “Think, Breathe and Act.” I’m inclined to focus on breathing first, taking a deep, slow, relaxing breath that can help flush out the gremlins threatening my resolve. Every breath must be measured and calm, keeping my heart rate low. Emotions will only distract me from success and use up precious gas supplies. Pragmatism and confidence must rule the moment, so that I can solve my dilemma and get out of the cave.

During an incident in Florida, my buddy became wedged in a very small space. When she turned to exit, a spaghetti cluster of discarded line snagged her gear. Struggling to free herself, she kicked up silt. I grasped the guide line and realized it was becoming taut as she shifted sideways in the tight passage. I could no longer see her in the murk, and tried to pull her back to a more open part of the tunnel. Then I felt the snap: I was holding the bitter end of our safety line in my hand. My buddy was still stuck, and one of my two regs, now full of silty clay, began to freeflow. My mind exploded with chattering monkeys; a million worries began to hijack my brain. Only a deep breath could turn off the terrible thoughts and refocus my attention on the tasks required for our survival.

Jill HeinerthProper training is essential for cave diving.

While I inhaled deeply, I told myself, “Emotions, you won’t serve me well right now.” And then I went to work, patching the guide line and rotating the sidemount tank valve open and closed for each individual breath. Needing both hands, I had to let go of my partner and lost her in the murk. I would search for her once I repaired our safety line.

Although it might sound terrifying, I did nothing heroic or remarkable. One by one, I solved my problems and completed the skills and drills that I learned during my cave-diving training. Nothing more. Touch contact, zero-viz line following, search procedures, patching a broken line, and emergency gas management got me home. Those actions were critical, but so were decisions I made before the dive. I had planned adequate gas reserves for an emergency. Had I cut corners, I would not have had the gas to manage an additional 73 minutes in the cave that day.

Learn from this

Freedivers and people who meditate understand the importance and power of proper breathing techniques. In scuba classes, instructors sometimes gloss over discussions about respiration and relegate breath control to the realm of gurus. After all, everyone breathes, all day, every day. In truth, few people practice breathing effectively. I would love to see every diver take a freediving class, to learn more about breathing and the astounding potential of human performance. Even if you don’t take a class, resolve to practice deep breathing as a technique for relaxation.

4. THINKING SMALL

Big problems are not solved quickly. In an area no taller than the space beneath your chair, the panicking diver in the previous anecdote became the cork in the bottle containing my life. I had to calm her down, repair our line and manage a failing breathing system. At that moment, trapped in a silty cave with broken life-support gear, it was tough to conjure up a vision of success—it was much more important to stay focused on the immediacy of my situation. Recognizing the need to take the next small yet decisive step toward a positive outcome saved my life. For 73 minutes beyond my dive plan, small victories added up, even as rescuers were rushing to the scene, expecting to recover my body. Small decisive actions can add up to big victories.

When I was a young cave diver, I recall hearing about a diver who became lost in a Florida system. He had failed to use proper navigational procedures for working in the complex network of passages. His choice left him in a state of confusion, without the backup of a guide line that could help him return to the entrance. In the last moments of his life, while his tanks were running dry, he chose to take time to write a note on his slate, recognizing his mistake and apologizing to his family. Would he have found his way had he used that precious time differently? It’s impossible to say, but I would stay focused and keep working toward solutions to the bitter end. Never give up hope.

Learn from this

In an emergency, remember to think small. Whether you are stuck or suffer an air-supply emergency, it can be overwhelming to envision what success might look like or when it will come. But we are all capable of knowing what the next best decision should be. By moving methodically toward a solution, one small step at a time, we can overcome terrible situations.

5. SUCCEEDING THROUGH FAILURE

Failure is a learning opportunity. Each incident or aborted dive informs me, through what I call discover learning. Scary milestones built the person I am today, and the entirety of those life experiences has made me wiser and stronger. By embracing every aspect of life, I’ve made significant discoveries that have built character and strength.

When a new student fails to clear a flooded mask in the pool and stands up coughing, we don’t eject them from class. A good instructor helps the new diver learn what went wrong so they succeed the next time. Each repeated drill teaches us to improve performance.

Knowing when to abort is as important as knowing how to dive. When you are within arm’s reach of the treasure you seek, listen to your intuition. When the hair stands up on the back of your neck, alerting you to danger, you must be willing to let go of your goals. Knowing when to turn back is as essential as conquering your fear and swimming into the unknown in the first place. Patient, diligent work is key to success. You might not achieve your goal the first time; you may have to get more training and gear. Allow fear to guide your decisions, and be willing to turn back.

During my first technical-diving course, I learned the most important lesson of my career. We had all been up late, preparing dive tables, gear and emergency plans. We had practiced our drills, and now all that was left was to conduct our first real decompression dive. On the way to the site, our instructor declared that he was going to reward us. To celebrate our hard work, he suggested we add five minutes to our dive plan and head 10 feet deeper, to have a look at an open hatch in the deck of a wreck. It was a minor shift in the plan, but suddenly my stomach was turning over. This was my deepest dive, and also my first decompression dive.

I looked at my elated classmates, recalculating tables and turn pressures. But to me it felt wrong. I was embarrassed, but I spoke up. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I don’t feel ready for this dive. I’m going to sit it out.” As my face flushed, I felt humiliated. I slunk onto the bench, leaned against my tanks, and watched everyone else get excited. My instructor patted me on the back. “Good call. We’ll finish your class another time.” But as everyone started to don their tanks, the instructor spoke again. “We’re not diving,” he said. Then he began to scold the team for allowing him to change the dive plan at the last moment. He had been testing us; I was being recognized for making the right choice. “Only Jill was courageous enough to abort a dive plan that was too advanced,” he said. “You have to be willing to use all your savings to get to the end of the earth, and then choose to skip a dive that isn’t right.” I never forgot that lesson. Willingness to abort before or during a dive is the ultimate rule of survivors.

Jill Heinerth"Be bold and confident in whatever you take on. When we courageously face the darkness of the caves in our life, almost anything is possible."

Learn from this

Through exploration, I envision the world as a great puzzle. What may seem impossible can be broken into manageable parts, where answers reveal themselves. With training, preparation and dedication to proper safety procedures, I have managed to maintain a career of nearly 30 years of exploration and science. It would be arrogant to say that I will never make a mistake or poor choice, but I am willing to take responsibility for risk. Be bold and confident in whatever you take on. When we courageously face the darkness of the caves in our life, almost anything is possible.