British Columbia Diving: Cold Water Rocks!

Growing up on the west coast of Canada, the ocean is featured in some of my earliest memories. As children, we’d plunge in, gasping at the frigid welcome, then would quickly retreat to warm ourselves on the sand or stone. I’ll admit that as a child, I was quite fearful of what lurked beneath the surface – surely some sea monsters resided in that dark, cold, seemingly bottomless sea.

It was decades later that I took the plunge and learned how to dive. I’ll admit now that it was not a bucket-list line item – far from it, in fact – but my husband, Mr G, had a strong hankering to dive, and, more afraid of being left behind than of the lurking unknowns, I agreed to try it with him. At the time, our children were quite young, so the classroom and pool sessions became date nights for us. We did our entire PADI certification in Vancouver, in early April, in wetsuits. The water temperature was a numbing 48 degrees, and the open-water dives were conducted in an inlet near the city, where there was very poor visibility and not a whole lot of life – mostly just a silted bottom, littered with discarded toilets and a few crabs scurrying around. In an ill-fitting rented 7 mm wetsuit, I was desperately cold during our four certification dives, but I girded my loins, buckled my fins, sucked it up and got ’er done. When I look back, remembering how fearful and cold I was, I think it is pretty miraculous that I saw it through.

We tried a few more cold-water dives in the years that followed (most of them as a part of our Advanced Open Water certification course), but we traveled to tropical destinations to enjoy easier, warm-water diving. After a gorgeous dive in Gabriola Passage one summer, we decided we really should dive more often in cold water, but recognized that to be able to enjoy it, we were going to need to buck up for some drysuits. After some initial newbie mistakes, we got comfortable in our drysuits, and have never looked back.

I can say, in all honesty, that the cold-water diving that is in my backyard is some of the best diving I have done in all of my travels – and that includes such wonderful destinations as Galapagos, Indonesia and Fiji.

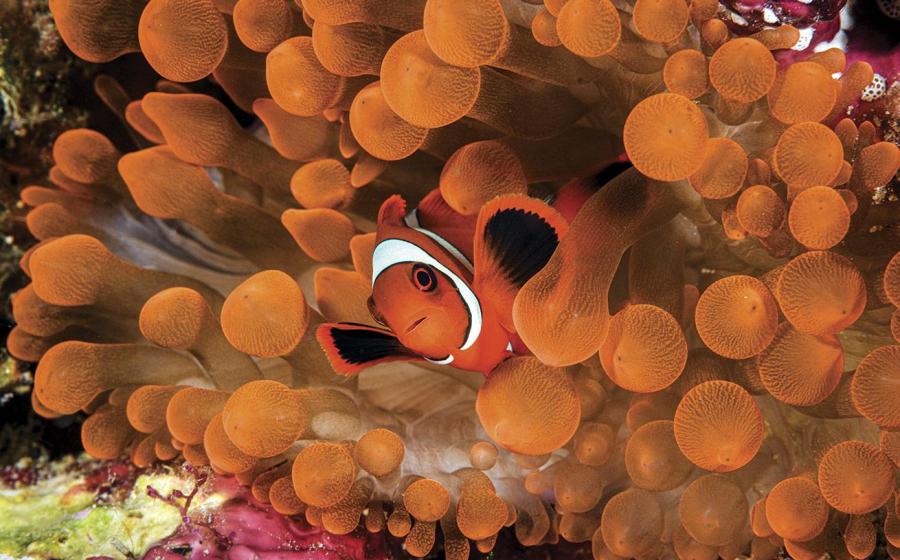

The colors in our cold water here in British Columbia are astonishing, but divers need a good light and to get in close to really appreciate all that is going on – without a light, the reefs look muted, indistinct. But shine a light on it? Wowza! The colors – orange, red, purple, yellow, green, blue – pop. The reefs are lively – dahlia-like anemones and nudibranchs and shrimps and sea stars and rockfish and barnacles and all sorts of other wondrous critters doing their thing. A light is also very handy for penetrating the dark ledges and crevices that abound, and you never know when you will see the telltale huge suckers of a Giant Pacific Octopus curled up in a cubby on the reef, or a wolf eel in its lair.

Much of the best diving in British Columbia is in current passages, where the movement of water brings plankton to the many invertebrates that pave the stony walls and slopes. A dive operator who is tuned in to the twice-daily high and low slack tides is critical. At full ebb or flow, some of the best dive sites are not safe to dive, due to ripping currents. And the best diving in British Columbia is in winter, when the summer plankton bloom that causes turbid water is gone. I’ve seen 100-foot visibility in February.

In addition to the unusual cast of creatures, there is another big difference between warm-water and cold-water diving – the gear: a much more cumbersome exposure suit (and usually a lot more lead to sink it), thick gloves that make gear and camera adjustments tricky, and a thick hood – and of course the bracingly cold water. Add to that (at times): low visibility, significant current and very steep terrain on which galloping descents are possible (this is when a buoyancy compensator can not fill quickly enough to create neutral buoyancy on a rapid descent, and has been cited as the cause for some cold-water diving fatalities). Even very experienced warm-water divers will be challenged the first few times they do a cold-water dive, especially if they are attempting it in a drysuit.

There are tons of great locations for diving in British Columbia. Nanaimo is famous for its two artificial reefs – the HMCS Saskatchewan and the HMCS Breton. Having been down many years now, they are completely encrusted with life. Snake Island and Clarke Rock off of Nanaimo are also fantastic dives, as are Dodd Narrows and Gabriola Passage. All of the above are within easy reach of land-based ops in Nanaimo, as well as a couple of live-aboards that operate in the area. To the south, the Gulf Islands offer lots of scenic locations for diving, as does Victoria, where the Ogden Point Breakwater is a very popular shore dive. To the north, Campbell River and Quadra Island in Discovery Passage (the scenic route of west coast cruise ships) offer world-class diving. And then there’s Port Hardy, a major attraction for cold-water divers. Closer to Vancouver are the Sunshine Coast and Howe Sound. And an easy drive from downtown Vancouver will get you to the marine parks at Whytecliff and Porteau Cove – both very popular shore dives.

In the gallery linked above, I’ve tried to include some imagery from various locations on the west coast of British Columbia. I hope they depict how truly special cold-water diving can be. Most of these were from my early days with an underwater camera – either my first, an Oly 4040Z digicam, and some later ones shot with my old Nikon D100. And this is just a very small sampling of the wonderful and diverse wildlife that can be found by diving in British Columbia. I’ll share more soon.

Judy G is an avid underwater photographer and traveler whose work has appeared in several dive publications. Judy also shares a comprehensive dive travel and photo blog.

No, he’s not really in space – but it kind of looks that way. We were at about 70 feet, and a dark winter’s day above left almost no natural light at this depth, despite the fairly clear winter water conditions. The reef, paved with sponges, strawberry anemones, sea stars, urchins and giant barnacles, is very typical for the dive sites in Discovery Passage, where this image was captured.

Judy G

I remember this octopus encounter very clearly – it was the first time we ever saw one out on the reef. Earlier sightings had been of bits of massive arms with silver dollar-sized suckers – daunting animals, tucked into the reef, that we were not brave enough to invite out to play. The GPO (Octopus dofleini) is the biggest variety of octopus in the ocean, and I am not kidding when I say big – they are fast growing, short-lived creatures that can reach well over 100 pounds in weight and have an arm span of over 20 feet. This one was much smaller than that – maybe about 15 pounds, so a juvenile, and it was curious. As we swam by, it reached out off the reef with two of its tentacles, as if waving us in. We stayed and admired it for many minutes, and eventually it wrapped an arm around Mr G’s arm, as if making friends. These are fascinating creatures, and I hope to share more stories and images of encounters in a future photo essay.

Judy G

Browning Wall, near Port Hardy, is likely the most famous of all dive sites in British Columbia, and with good reason. The wall is very colorful and paved with life. I’ve only had the opportunity to dive it once, but I have promised myself that I will return soon. This beautiful topside scenery is very typical of British Columbia coastline.

Judy G

I captured this image right in Seymour Narrows, which is in the heart of Discovery Passage, and is the fastest flowing tidal pass in British Columbia, with a top speed of about 16 knots. This dive requires impeccable timing, as it can only safely be dived at slack water – depending on the size of the tidal exchange, it can be a very short, but wildly beautiful dive. I have never seen an aggregation of so many of these pretty painted anemones (Urticina crassicornis) anywhere else I have dived.

Judy G

This beautiful nudibranch (Melibe leonine) is mesmerizing as it sweeps the water with its hooded appendage, and it can swim if disturbed. These are apparently quite common, especially north in Alaska, but I have only spotted two, both on this same dive, on an island reef near Discovery Passage.

Judy G

This funny-faced fish is a Red Irish Lord (Hemilepidotus hemilepidotus), a member of the sculpin family. This fish was camped out on Browning Wall, near Port Hardy, surrounded by sponges and white plumose anemones. They can grow to be about 18 inches in length.

Judy G

I share this image to demonstrate that even such simple (and painful to contact!) critters as sea urchins are wildly colored in our cold waters. There are purple (Strongylocentrotus pupuratus), red (Strongylocentrotus franciscanus) and green (Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis) urchins featured in this image. It is quite common to see large aggregations of urchins like this on many sites.

Judy G

I captured this image of our oldest daughter and an inquisitive harbor seal (Phoca vitulina richardsi) at Snake Island, near Nanaimo. We were just finishing up our dive in a shallow bay of the island (the site is famous for its wall dive), and along moseyed this bright-eyed character from out of the gloom. He (or she) swam right up to our daughter, placed his or her nose on her mask, and gave her a playful little nudge. I barely had time to get the camera up before the encounter was over. The not-great visibility and quick camera work netted a not-so-perfect image (due in part to the abundant backscatter), but I still smile at the memory when I see it.

Judy G

So there we were at Snake Island, in about 20 feet of water, right after the harbor seal love, and I came across this pair of rock crabs mating. Check out the expression of the one on top – he does not look pleased at the intrusion.

Judy G

There are sites I’ve dove in British Columbia that are thick with nudibranchs. Seriously. And we’ve got some big nudibranchs too, including the fairly common Giant Dendronotid (Dendronotid iris), which grow up to 10 inches in length. This little beauty was much smaller than that, at about 2 inches long.

Judy G

These big boys (and girls) are the largest variety of sea lions on the planet, with females growing up to 8 feet in length and weighing up to 600 pounds, and with males up to 10 feet in length and tipping the scales at over 2000 pounds. So they are big and very noisy. At the Steller Sea Lion rookery at Mitlenatch Island, near Discovery Passage, it is common to see large aggregations like these. I’ve also seen (and heard!) them near Gabriola Passage, through which they migrate, and on rocky islets in the southern part of Haida Gwaii (Queen Charlotte Islands). Although I have seen them on a couple of occasions underwater while diving, I have yet to capture a decent image. When one of these big boys or girls swims by, it is both awesome and a bit intimidating.

Judy G

Puget Sound is near Seattle, and this crab (and many more like it) are found in Discovery Passage in British Columbia, several hundred miles to the north, so they are a long way from home ;^) Seriously, this is a big variety of crab – its carapace can be up to 12 inches in diameter (and I swear I’ve seen a few that were bigger than that). I suspect that they are probably pretty good eating, but the many I have seen are fortunate to find themselves within the marine reserve at Quadra Island, and are safe from human predation. Puget Sound King Crabs (Lopholithodes mandtii) are gorgeous in coloration (can you find the eyes? – hint – they are red), and can be quite easily approached. Just don’t get snagged by their huge crushing claw…

Judy G

These wonderful fish are a favorite of Pacific cold-water divers. They are neither wolf-like nor an eel – instead, they are a very elongated fish with a face that looks like something out of the Muppets. They are quite shy and reclusive, but have been known to be friendly with divers, especially those who offer them a cracked urchin as a peace offering. They have remarkably strong jaws with which they can crush urchins, crabs and shellfish. The wolf eel (Anarrhichthys ocellatus) is a long-lived animal, and the males can apparently grow up to 7 feet in length and 40 pounds. I’ve only had the thrill of seeing a couple of these fantastic animals – and this is the only one I have been able to photograph. I only got this one shot of him before he retreated into his den. This image was captured at Clarke Rock, near Nanaimo.

Judy G

Growing up on the west coast of Canada, the ocean is featured in some of my earliest memories. As children, we’d plunge in, gasping at the frigid welcome, then would quickly retreat to warm ourselves on the sand or stone. I’ll admit that as a child, I was quite fearful of what lurked beneath the surface – surely some sea monsters resided in that dark, cold, seemingly bottomless sea.

It was decades later that I took the plunge and learned how to dive. I’ll admit now that it was not a bucket-list line item – far from it, in fact – but my husband, Mr G, had a strong hankering to dive, and, more afraid of being left behind than of the lurking unknowns, I agreed to try it with him. At the time, our children were quite young, so the classroom and pool sessions became date nights for us. We did our entire PADI certification in Vancouver, in early April, in wetsuits. The water temperature was a numbing 48 degrees, and the open-water dives were conducted in an inlet near the city, where there was very poor visibility and not a whole lot of life – mostly just a silted bottom, littered with discarded toilets and a few crabs scurrying around. In an ill-fitting rented 7 mm wetsuit, I was desperately cold during our four certification dives, but I girded my loins, buckled my fins, sucked it up and got ’er done. When I look back, remembering how fearful and cold I was, I think it is pretty miraculous that I saw it through.

We tried a few more cold-water dives in the years that followed (most of them as a part of our Advanced Open Water certification course), but we traveled to tropical destinations to enjoy easier, warm-water diving. After a gorgeous dive in Gabriola Passage one summer, we decided we really should dive more often in cold water, but recognized that to be able to enjoy it, we were going to need to buck up for some drysuits. After some initial newbie mistakes, we got comfortable in our drysuits, and have never looked back.

I can say, in all honesty, that the cold-water diving that is in my backyard is some of the best diving I have done in all of my travels – and that includes such wonderful destinations as Galapagos, Indonesia and Fiji.

The colors in our cold water here in British Columbia are astonishing, but divers need a good light and to get in close to really appreciate all that is going on – without a light, the reefs look muted, indistinct. But shine a light on it? Wowza! The colors – orange, red, purple, yellow, green, blue – pop. The reefs are lively – dahlia-like anemones and nudibranchs and shrimps and sea stars and rockfish and barnacles and all sorts of other wondrous critters doing their thing. A light is also very handy for penetrating the dark ledges and crevices that abound, and you never know when you will see the telltale huge suckers of a Giant Pacific Octopus curled up in a cubby on the reef, or a wolf eel in its lair.

Much of the best diving in British Columbia is in current passages, where the movement of water brings plankton to the many invertebrates that pave the stony walls and slopes. A dive operator who is tuned in to the twice-daily high and low slack tides is critical. At full ebb or flow, some of the best dive sites are not safe to dive, due to ripping currents. And the best diving in British Columbia is in winter, when the summer plankton bloom that causes turbid water is gone. I’ve seen 100-foot visibility in February.

In addition to the unusual cast of creatures, there is another big difference between warm-water and cold-water diving – the gear: a much more cumbersome exposure suit (and usually a lot more lead to sink it), thick gloves that make gear and camera adjustments tricky, and a thick hood – and of course the bracingly cold water. Add to that (at times): low visibility, significant current and very steep terrain on which galloping descents are possible (this is when a buoyancy compensator can not fill quickly enough to create neutral buoyancy on a rapid descent, and has been cited as the cause for some cold-water diving fatalities). Even very experienced warm-water divers will be challenged the first few times they do a cold-water dive, especially if they are attempting it in a drysuit.

There are tons of great locations for diving in British Columbia. Nanaimo is famous for its two artificial reefs – the HMCS Saskatchewan and the HMCS Breton. Having been down many years now, they are completely encrusted with life. Snake Island and Clarke Rock off of Nanaimo are also fantastic dives, as are Dodd Narrows and Gabriola Passage. All of the above are within easy reach of land-based ops in Nanaimo, as well as a couple of live-aboards that operate in the area. To the south, the Gulf Islands offer lots of scenic locations for diving, as does Victoria, where the Ogden Point Breakwater is a very popular shore dive. To the north, Campbell River and Quadra Island in Discovery Passage (the scenic route of west coast cruise ships) offer world-class diving. And then there’s Port Hardy, a major attraction for cold-water divers. Closer to Vancouver are the Sunshine Coast and Howe Sound. And an easy drive from downtown Vancouver will get you to the marine parks at Whytecliff and Porteau Cove – both very popular shore dives.

In the gallery linked above, I’ve tried to include some imagery from various locations on the west coast of British Columbia. I hope they depict how truly special cold-water diving can be. Most of these were from my early days with an underwater camera – either my first, an Oly 4040Z digicam, and some later ones shot with my old Nikon D100. And this is just a very small sampling of the wonderful and diverse wildlife that can be found by diving in British Columbia. I’ll share more soon.

Judy G is an avid underwater photographer and traveler whose work has appeared in several dive publications. Judy also shares a comprehensive dive travel and photo blog.