Oman's Undersea Riches Pay Off for Scuba Divers

Manage your expectations, I tell myself.

We’re out here at the edge of the world, where “all dives are exploration dives,” cruise director Shaker Mohamed says in our first briefing. Let that be enough, I think.

Still, you can’t help but wonder what might be out here, just off the ancient town of Mirbat, around 75 miles from Oman’s Hallaniyat Islands.

In the back of every diver’s mind: the Hallaniyats’ elusive pod of Arabian Sea humpbacks, perhaps the world’s only nonmigratory group, now so isolated from the global population that they might be considered a distinct species.

We never do spy whales, but something big shows up on that very first dive. And it’s getting bigger as it approaches divers and gains scale in the hazy viz. A shark, for sure. Tiger? Bigger.

And then the white stars on its dark skin begin to shine. Whale shark! A juvenile, less than 20 feet long, as gentle as can be, mesmerizing a half-dozen divers with just the wide, smooth swish of its magnificent tail. As we’re high-fiving, a dozen mobula rays fly through, silhouetted against the greenish, particulate-filled water. As we’re digesting that, back comes the whale shark, making another leisurely pass, clearly undisturbed by our presence.

Divers are relatively new here, so it’s hard to guess what it’s thinking — perhaps just curious. It’s mutual.

Scott JohnsonRugged cliffs can end at sandy beaches or plunge straight to the deep.

Land of Frankincense

Ever since early man exited Africa and took a right down the Arabian coast at least 100,000 years ago, curiosity has driven the urge to roam. More than 2,000 years before the Victorians would make leisure travel accessible, we journeyed not only for knowledge, but also for gain. And few endeavors stood to produce as much gain as the trade in frankincense, a fragrant resin made from the sappy tears of a scrubby little desert tree. Valued by the Romans as dearly as gold, counted among the Magis’ gifts to the infant Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew, frankincense was produced almost entirely in Oman’s rugged, mountainous Dhofar region, home to Salalah, departure port for the new Oman Aggressor.

“Increasingly easy travel and a culture long used to foreigners explain why Oman is one of the fastest-growing tourist destinations in the world.”

At Sumhuram, an archaeological park and UNESCO World Heritage Site 25 miles east of Salalah, the frankincense trade flourished for nearly a thousand years, from about the fourth century B.C. to the fifth century A.D. Visitors today can clearly see that here the sea was paramount — provider and defender — carving a perfect harbor below the butte from which the bustling fortress commanded the countryside.

In the heart of Salalah lies the remains of the port of Al-Baleed, another World Heritage site that supported the frankincense trade from about 800 to 1600. Today it’s home to a terrific history and maritime museum and a huge active archaeological site, exposing the bones of a city that welcomed foreign visitors for 800 years — Marco Polo visited Al-Baleed in 1290 and pronounced it beautiful.

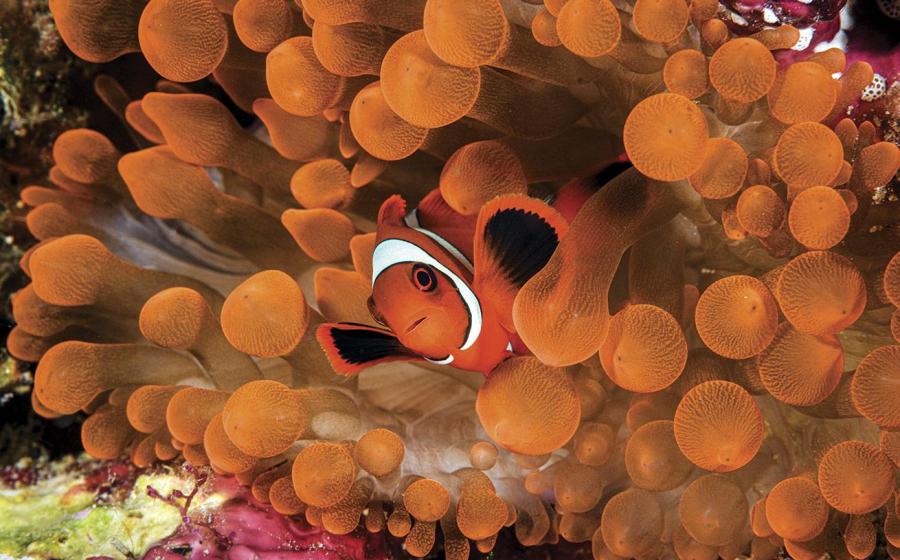

Scott Johnson (2); Tobias FriedrichLeft to right: Oman anemonefish are perhaps the cutest of the many endemic species found in Oman’s waters, including the Oman hawkfish and Arabian butterflyfish; an inquisitive pharaoh cuttlefish investigates a photographer off oddly named Schmies Island; harder to spot but keenly sought by divers and underwater photographers are dragon morays (Enchelycore pardalis).

It still is. Present-day Salalah is a holiday beach town for both Arabs and Europeans, with a gleaming, modern city center — any American mall rat would be at home in multistory Salalah Gardens, with its food court and movie theater — and mile upon mile of glorious white-sand beach fronting pale-jade surf of surprising clarity.

Oman Aggressor is based here at a newly built marina and hotel complex for about six months of the year. (The yacht also dives the Daymaniyat Islands from Muscat, Oman’s capital, and Musandam, in the Gulf of Oman.) Mirbat is our first dive, but our true target this week is the Hallaniyats, about 25 miles east off the Dhofar coast.

When part of Vasco da Gama’s armada came through these islands in 1503 — the wreck of his Esmeralda lies in a restricted area off Al-Hallaniyah, the largest of the five islands — it took months to get here from Lisbon. Today there are numerous direct flights from the U.S. to Dubai, just a two-hour connection from Salalah. Increasingly easy travel and a culture long used to foreigners explain why Oman is one of the fastest-growing tourist destinations in the world.

It’s hard to imagine an easier or more-pleasant form of travel than Oman Aggressor, a 148-foot luxury yacht renovated from the hull up — “really a piece of art,” Mohamed says with pride, and he’s not wrong. Its mostly Egyptian crew cut its dive teeth in the Red Sea, and is both experienced and eager to please; its attention and care will make you feel like the Queen of Sheba, who, coincidentally, is said to have had a summer palace at Sumhuram — Dhofar frankincense was among her gifts to Solomon.

Seabirds and Sherbert

We rise the next day to a crescent moon and bright stars, symbols of the Middle East since Nebuchadnezzar’s time, hung in a sky streaked like layers of peach, raspberry and tangerine sherbet (derived from the Arab word sharba, a drink). Seabirds are silhouettes sketched against the sparkling lights of Mirbat’s minarets. Coastal mountains soar to 2,000 feet, jagged black outlines that soften with the sun’s rays into folds of undulating stone. It’s all heartbreakingly beautiful, in a Lawrence of Arabia sort of way.

Unlike most of the 13 divers aboard, Jim Maxwell, a retired U.S. military officer from Carlsbad, California, has experience traveling in the Middle East. While not much tops his first whale shark — “on the very first dive!” — he was drawn here by “the history and the culture. I wanted to see the frankincense trail, and a part of the Middle East I had not explored.”

Tobias FriedrichRight to left: Native but not especially prevalent, lionfish are at home among the soft corals decorating the wreck of the City of Winchester, a World War II-era ship lying off Al-Hallaniyah. Far more elusive are the Hallaniyats’ pod of Arabian Sea humpbacks, seen here off the island of Al-Sawda. The pod does not migrate — perhaps the only pod in the world that does not — and scientists debate whether the isolated group now constitutes its own subspecies.

Exploration is why most of us are here. Everywhere we’re conscious that, at least underwater, we are seeing places not many have seen, in an area that receives very few divers a year. Briefing us on a plunge that, like many in the Hallaniyats, starts with an underwater pinnacle and ends in the blue, Mohamed reassures us: “If you find a big boat, it’s us.”

At a site called Hasikiyah Arch, off tiny Al-Hasikiyah island, we leave the “big boat” aboard Oman Aggressor’s two pangas and drop down over huge stone fingers to a glassfish-filled cavern, bumping into one of the biggest day octopuses I’ve seen. Meandering along wide, sandy channels between fingers, we find a school of sweepers that moves like a living piece of Arabic script, forming straight lines that suddenly make flowing arabesques before turning in a new direction en masse. Magical. We could have stayed all day.

At Gotta Qibliyah off Al-Qibliyah, the Hallaniyats’ easternmost isle, a triangular opening in the wall gives way to an arched cathedral, where our lights make gorgeous patterns; natural light leads to the exit, where we spy a shy dragon moray, Enchelycore pardalis. Nonstinging (mostly) jellies of a delicate pink with darker accents mesmerize on our safety stop, many with a tiny fish inside; whether commensal travelers or doomed prey, we cannot say.

All of us remark on the eels we’re seeing on every dive. Oman is lousy with morays, most of a girth that amazes. Not impressed with eels? Consider the little lilac-gray geometric moray — Gymnothorax griseus — whose delicate black-spot patterns, traced on its head, can remind you of the intricate henna designs you might glimpse on the hands of local women. A “simultaneous hermaphrodite,” it can release up to 12,000 eggs per spawn, which might explain why they’re everywhere. Maxwell, my dive buddy, is taken with perhaps the most common eel here, the massive honeycomb, or laced moray, Gymnothorax favagineus. “I’ve never seen one before — so huge!” he exclaims.

Aggressor LiveaboardsOman Aggressor anchored off Al-Qibliyah.

It’s not just the eels. Everything seems bigger here, from parrotfish to rainbow runners to black-blotched rays to the gazillion active nudibranchs — many 6 inches or more in length, including a couple of Spanish dancers in the 15-inch range — galloping across nearly every site. (Mohamed spots 15 on our first dive alone.)

Again and again we encounter vast schools of many types of fish, contiguous but distinct, lined up like chapters in a book. Packed with a density that’s hard to conceive, they can be parted only by swimming through them, like entering the beating heart of a many-celled organism, one giant living thing.

“This, as always, is why we roam: To behold the wonderful and strange, the things we have not seen, and perhaps not even imagined.”

But nothing tops a wondrous animal we encounter at Angry Grouper, a super-fishy site off Al-Hallaniyah.

Kicking hard against a decent current, we fly over a soft-coral-covered seamount and tuck into a sandy cross channel where we startle two rays the size of coffee tables. Finning through a lovely, lacy field of the bushiest black coral ever, we sail over the next ridge and right into a ray perhaps 4 feet across. Over another hill and — bam! Something big, maybe 8 feet long, rests on the sand. A nurse-type shark, but what the heck? Mushroom brown with dark spots, an enormous scythed tail and ridges running the length of its back like a leatherback turtle, it was the confusingly named zebra shark, Stegostoma fasciatum — juveniles boast black-and-white stripes — a bucket-list encounter with a strange and beautiful creature.

This, as always, is why we roam: to behold the wonderful and strange, the things we have not seen, and perhaps not even imagined.

Scott JohnsonA zebra shark — so named because juveniles have black-and-white stripes — rests at Anemone Reef off Al-Hallaniyah; blue-barred parrotfish inhabit the shallow Marriott Wreck off Mirbat, a fish-filled dive.

The Human Connection

For all the gains Oman has made since the present sultan began building a modern state in 1970, life here can seem strange to Americans. Omanis live under an absolute monarchy with zero guarantee of the basic freedoms Americans take for granted. For some, that might be a reason not to come. But how then does the unknown world become known?

I keep going back to an encounter at the Salalah Gardens food court. As I passed a table of chattering, black-clad women draped head to toe, one was frantically beckoning to me. I paused, unsure — for a stranger to approach such women could be bad manners at best or an insult at worst.

But even through her veil, I could see she was beaming, her eyes telegraphing a huge grin. Her hand gesture was just a wave. I shyly returned her greeting and moved on.

What did she want from me that I could give in that moment? A smile. A connection. For thousands of years now, it’s been a good place to start.

Need to Know

When to Go: Oman Aggressor dives the Hallaniyat Islands November through April; May through October it is based in Muscat and dives the Gulf of Oman and the Musandam Peninsula.

Travel Tip: Qatar Airways and Emirates Airline fly direct from U.S. hubs to Doha and Dubai, respectively. Salalah is about a two-hour flight from either. (When flying through Dubai, add extra time: The airport is vast, and requires a 30-minute bus ride from international to local terminals, where your Salalah flight will depart.) Oman requires an entrance visa — around $50 USD — that can be procured before you depart.

Dive Conditions: Conditions vary with the season in the Hallaniyats. Water temps might be cooler — in the low 70s — and currents milder in winter, with visibility from 30 to 60 feet; for repetitive dives, a 5 mm fullsuit or greater, along with gloves and a hood, is desirable. Spring brings better viz but stronger currents. In summer, when the yacht moves to Muscat, the Dhofar coast experiences the Khareef, or monsoon, a unique weather pattern that draws Arab tourists from all over to experience the cool, wet weather that turns mountain riverbeds into plunging waterfalls and dry “wadis,” or valleys, into verdant oases.

Operator: Oman Aggressor is the largest and most luxurious of Aggressor Liveaboards’ yachts. The sleek, 148-foot beauty has a beam of 28 feet and yields a stable, comfortable ride. It carries 13 crew (including its own pastry chef) and up to 22 passengers in 11 staterooms that feature single and king beds, not bunks, and en suite baths. Diving is from the mothership and its two 23-foot pangas.

Price Tag: A seven-night Hallaniyats cruise starts at $3,515; through December 31, a special offer takes $700 to $1,000 off that price. Oman cruises can be combined to include more than one itinerary. Aggressor Travel can help you book land excursions to Sumhuram, Al-Baleed, and other cultural and historic sites.