A Local's Guide to Diving in Ireland

Brandon ColeBright, multicolored jewel anemones (Corynactis viridis) carpet a large rock in the Skellig Islands.

We first floated the idea a few years back. It would be like a home swap, but rather than a holiday spent in each other’s condos playing board games and binging Netflix, we would organize a scuba tour of our respective home waters and share quality bottom time. My wife, Melissa, and I were first to play host, treating three Irish friends to many of Western Canada’s underwater star attractions around Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Quid pro quo, and there we were a year later, thousands of miles away in the Atlantic Ocean being snuffled by seals.

Related Reading: 8 Best Places to Go Kelp Diving

Brandon ColeFrom top: Divers get ready before plunging into Irish waters; friendly gray seals interact with snorkelers.

Dressed Up In Dublin

Nothing says fáilte go hÉirinn (welcome to Ireland) like a wet, whiskered kiss from a friendly gray seal. Three are in the shallows at Dalkey Island in the suburbs south of Dublin. They are similar to harbor seals back home, but these pinnipeds are larger and have longer faces. One seal plays hide and seek with us, disappearing behind columns of seaweed for a moment and then coyly peering around the kelp tangles to confirm we are still watching. Another mostly ignores us, choosing instead to snooze on the seabed’s carpet of algal litter just beneath us. The third seal is everyone’s best friend—at least for today. The seals’ moods are mercurial, one day gregarious and the next aloof. Today our welcoming committee nuzzles our cameras, nibbles our fins, and even hugs our arms and legs with its flippers.

Snorkeling with the seals is so much craic (Irish slang for “fun”) I almost forget about the 60-degree water free-flowing between my neck and nether regions. Our checked luggage did not arrive with our persons on the plane yesterday, so our drysuits and much more are MIA courtesy of Aer Lingus.

Brandon ColeRuins from past occupants dot the now uninhabited Dalkey Island.

Nonetheless, things are grand. With a triple-layered ensemble of three almost-but-not-quite-right sized wetsuits loaned to me by our dear friend Nigel, I remain submerged with the seals for two hours.

I first met Nigel 20 years ago while photographing sharks in the Bahamas. The stunning images from the Dublin-based diver’s native waters first put Ireland on my radar, and through him, Melissa and I met our other Irish dive buddies. Today, if not for Nigel’s generosity, I would be bobbing around in nothing but my underwear on this dive.

Monica MedinaMap of Ireland dive sites.

Even if the airline does not find our wayward bags and deliver our personal kit, we will not just survive but thrive in the weeks ahead during this cross-country expedition. The indomitable optimism of Nigel and the other local lads we’ll be meeting, backed by their 100-plus years of combined experience with all things Irish scuba, will certainly bring everything together and see things right. Their site knowledge and critter lore are top-shelf, they have their own boats and they know divers in every harbor. We are honored guests in their capable hands, traveling their green lands. Our prospects are as bright as the warm August sun shining down on us and Dalkey’s seals.

Shelter From The Storm

Brandon ColeA tompot blenny (Parablennius gattorugine) squeezes into a rocky crevice.

The airline redeems itself. Two days later we are on the road in a rented van with our own heretofore missing kit. We follow Nigel north on the M1 from Dublin, passing from the Republic of Ireland into and through Northern Ireland, and then back into the Republic to finally reach Portsalon in County Donegal five hours later.

Nick, the second Irish fella participating in our dual-ocean dive swap deal, has driven up from his home on the west coast in Galway. He brings an army of tanks, a compressor and his rigid inflatable boat. The sweet 24-foot-long RIB is our sea chariot for the next week.

In Mulroy Bay I see my first Atlantic lobsters: the 2-foot-long common European lobster, with huge claws and blue legs, and the smaller spiny “cray” species, without pincers. There are new goby species and new sea stars for my lifetime global critter list. We find scallops as wide as my hand, decorator crabs masquerading as antler-shaped orange sponges and sea anemones with pink-tipped tentacles that remind me of aggregating anemones in my own backyard waters.

As a marine ecologist and photographer, Nick has surveyed Mulroy Bay and its connected sheltered waterways for his work. He tells us this sea loch, or inlet, is one of just a few places in all of Ireland where we can safely dive today. Though we do not feel it now—nor did we back in Dublin—the Emerald Isle is being pummeled by an angry Storm Betty. Two miles away from us, on the other side of an impossibly green hill, is the vast, sometimes pitiless North Atlantic Ocean. To use the local vernacular, it’s “blowing a hooley” out there, and apparently has been for “donkey’s years.” This has been an unprecedented year, our friends sadly relate. Storm after storm has delivered gale force winds and lashing rain for months on end, preventing almost all diving along the exposed northern, western and southern coastlines of their fair Eire.

Related Reading: Getting to Know Greenland's Frosty Critters

Brandon ColeFrom top: The author’s wife, Melissa, admires a compass jellyfish drifting by in the water column; a European lobster, its two huge claws on full display.

Over a midnight dinner of frozen pizzas in our rented holiday home, we discuss strategy while the portable Bauer Junior II compressor drones away, filling cylinders for the morrow. The latest weather forecast may just give us a break, a chance to briefly escape the bay and taste the open sea.

Trailering the boat to another boat ramp, we launch and motor 5 miles north to Melmore Head and its panoramic view out onto big water. To be sure, it is most definitely still hooleying, the wind screaming like two banshees fighting to the death while falling off a cliff. The ocean’s surface is also scary, white and whipped up like frosting on a cake. But the weather is coming hard from the west. Captain Nick wisely reverses course a quarter mile and snugs up tight against the rocky headland’s eastern flank. Now completely out of the maelstrom raging off Donegal’s front porch, we excitedly gear up and dive down.

The 30-foot visibility surprises, much better than Mulroy Bay. Dozens of compass jellyfish pulse through the blue-green water. Some of the stinging beauties host juvenile fish (e.g., pollack or whiting) darting among their frilly tentacles. I snap pictures and then exchange my macro camera for Melissa’s wide-angle system. The caramel-colored kelp cascading down the wall catches my eye. After losing myself in the viewfinder trying to create plant art, I switch back to macro to happily stalk fish—pollack, sculpins unknown to me and similarly strange wrasses. We spy our first conger eel lairing between rocks at 70 feet. This exploratory dive at an unnamed site is excellent and likely a hint of what we would have experienced along the outer coast had conditions been more cooperative.

Brandon ColeFrom top right: Connemara’s Kylemore Abbey, built as a castle in 1868 and founded as a place of worship in 1920; a small-spotted catshark rests on the bottom during the daytime, when the species is less active. Opposite: A cuckoo wrasse fins past a limestone reef adorned with gorgonians and soft corals known as dead man’s fingers.

A Step Back In Time

The assault on the north coast is supposed to resume, so our friends suggest we reposition. We drive southwest five hours and set up a new nomadic base camp to dive Killary Harbour, a fjord carved out by a glacier 20,000 years ago. Dive clubs from around the country come to Killary in winter when storms wipe out other west coast sites. The lads introduce us to more new critters, including orange langoustine mini lobsters and small-spotted catsharks. Also called dogfish, these sharks are harmless bottom dwellers that grow to 3 feet long and feed on benthic invertebrates and small fishes. We spot their leathery egg cases attached to seaweed sprigs and hydroid bushes. Backlighting one with a torch, we can see the developing shark embryo’s silhouette, wriggling like a cute, wee gummy worm. We’re happy to be wet in the wilds of Connemara.

Backlighting one with a torch, we can see the developing shark embryo’s silhouette, wriggling like a cute, wee gummy worm. We’re happy to be wet in the wilds of Connemara.

Nick used to run a dive school and charter business in the Aran Islands in Galway Bay. He still visits regularly for both scientific work and fun. During a lull in the rubbish weather, he takes us to Inishmore for a drift dive along current-swept limestone ledges in 50 to 90 feet. A shoal of pollack loiter in the kelp on the plateau above the ledges. The eroded undercuts below are decorated with sponges, white gorgonians and soft corals called dead man’s fingers. Between our dives, I fly (via my drone) back in time 3,000 years to the Bronze Age. Hovering overtop the remains of Dun Aengus, a prehistoric hill fort perched on the extreme edge of Inishmore’s plunging cliffs, deepens my fascination with this ancient island nation.

Brandon ColeClockwise from left: A minuscule bobtail squid rests on the sand; beehiveshaped monastic huts and a graveyard on Skellig Michael; dead man’s fingers, jewel anemones, a sea urchin and bloody Henry sea star on a pinnacle off Valentia Island on Ireland’s western coast.

Jeweled Reefs And Beehive Huts

Silly me. I thought we must surely have already maxed out in Ireland’s scenic grandeur department above and below the waves, but then we trundled into County Kerry to meet up with Michael. Lad number three in our foreign-exchange hospitality program, Michael would now graciously show us around his dramatic, fantastic Iveragh Peninsula. With additional support so unsparingly provided by other fine members of the Kerry Sub Aqua Club, our last week is destined to be absolutely outstanding, or more accurately, cracking.

At Cuasdiarmuid we explore an invertebrateencrusted deep pinnacle peaking at 80 feet, a wall glowing with lime green jeweled anemones and a kelp forest in which we uncover a bull huss, the greater spotted catshark. This crowd fave site along Valentia Island also has crays, scorpionfish and super photogenic tompot blennies. A site called Snowy Bullig proves happy hunting grounds for red blennies, more bushy-eyebrowed tompots, more sharks and velvet swimming crabs.

Prepping for a midnight shore dive in Kells Bay to document the nocturnal activities of bobtail squid, we hear the tale of how Michael has been, more than once, called upon by the local community for special duty—specifically, that of rescuing cows and sheep who fall off cliffs into the sea. Never doubt the skills and altruism of a Kerryman! While photographing the bobtail squids I keep glancing up, half expecting to see flailing hooves.

Two specks on the horizon when seen from the Cliffs of Kerry, the Skelligs are cloaked in both history and mystery. Boats bring tourists to Skellig Michael, the larger of the two islands, to climb hundreds of steps to the summit, where Christian monks lived in spartan, weather-worn stone huts shaped like beehives between the sixth and 12th centuries.

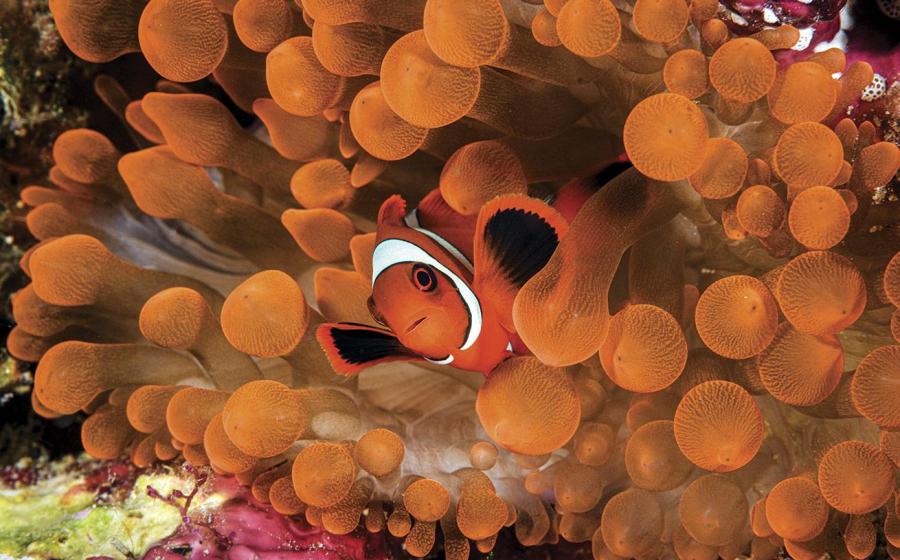

Colonies of jeweled anemones in a patchwork of rainbowed colors form living quilts draped down some structures. Fuzzy clumps of orange and yellow soft corals are plastered over others.

But the islands are rarely dived. When the lads finally report that the weather looks favorable, I am mad keen to go. Ten of us set off from Portmagee in three inflatables for the 11-mile run. Skellig Michael beneath the waterline mirrors its profile above: imposing and impressive. Washerwoman Rocks is a notoriously high-energy dive site that sometimes challenges the best with strong currents and surge. Luckily, we’re meeting the laundry lass on a mellow day and drop easily past 100 feet into a gully, then commence a zigzag ascent up a ragged rock face on which spider crabs march across swaths of dead man’s fingers accented by sea stars and pink urchins.

At Landing Pinnacle, Melissa and I descend with our guides into a giant’s playground of gargantuan, angled slabs of rock. Some formations are serrated like shark teeth, others are sheer, shadowy monoliths rooted in the abyss. Colonies of jeweled anemones in a patchwork of rainbowed colors form living quilts draped down some structures. Fuzzy clumps of orange and yellow soft corals are plastered over others. There’s also the usual compliment of crawling crustaceans and flitting fish. I’m determined to capture images of everything, including the spectacular male cuckoo wrasse gaudily painted in blue, yellow and red that leads me on a merry chase. I weep when my NDL time and gas supply signal that time’s up. At least the lion’s mane jellyfish trailing a rat’s nest of spaghetti-like tentacles provides us with a memorable parting gift on the safety stop. What a phenomenal dive, arguably the trip’s best.

A couple of hours later we are standing among the monastic cells 700 feet above sea level, staring to infinity and smiling. In the Star Wars movies, exiled Luke Skywalker brooded alone atop this same desolate rock. But we have come to Ireland—to the Skelligs and so many other wonderful places—to enjoy the company of great friends and celebrate the dark, enchanting seas swirling below.

Related Reading: Meet the Women Leading 'Mission: Iconic Reefs'

Brandon ColeThe ruins of Dun Aengus, an ancient fort that dates to the Bronze Age, overlook the sea on Inishmore, one of the Aran Islands off the Galway coast.

Need To Know

When To Go

Topside weather is generally best in summer and early fall. Rain and wind are possible anytime. Storms make planning a dive trip in winter too risky.

Dive Conditions

Ocean temperatures range from the high 40s in winter to low 60s in summer. Depending on the season and your thermal tolerance, drysuits or 7 mm wetsuits are advised. Visibility ranges from 10 to 75 feet. Fall and winter usually have the best clarity, with less plankton than spring and summer. Surge and current can make diving challenging. When strong winds and rough seas prohibit diving along exposed coastlines and at offshore islands, play it safe and explore sheltered sites in the sea lochs.

Travel Tips

Dive shops are scattered around Ireland, and there are a few charter boats, but most diving is either on your own or more commonly with local scuba clubs, of which there are many. The club scene is very active, and most have their own boats and portable compressors.

Visit diving.ie to start your dive research. Connect with local subaqua clubs and introduce yourself. Irish hospitality is legendary.

Incoming morning tide is generally best for the seals at Dalkey Island. Don’t bother with scuba gear. Snorkeling is easier since you must transport all your kit across on a little ferry boat.

Take time to experience Ireland above the waves. Go hiking, visit a castle, drive the Wild Atlantic Way and raise a pint or three in a real Irish pub.

PADI Five Star Dive Centers

Dublin/Dalkey Island Oceandivers; oceandivers.ie

Portsalon/Mulroy Bay Aquaholics; aquaholics.co.uk

Connemara/Aran Islands Scubadive West; scubadivewest.com

Skellig Islands Waterworld Dive Centre; waterworld.ie