Flying After Scuba Diving Makes DCS Symptoms Worse - Lessons for Life

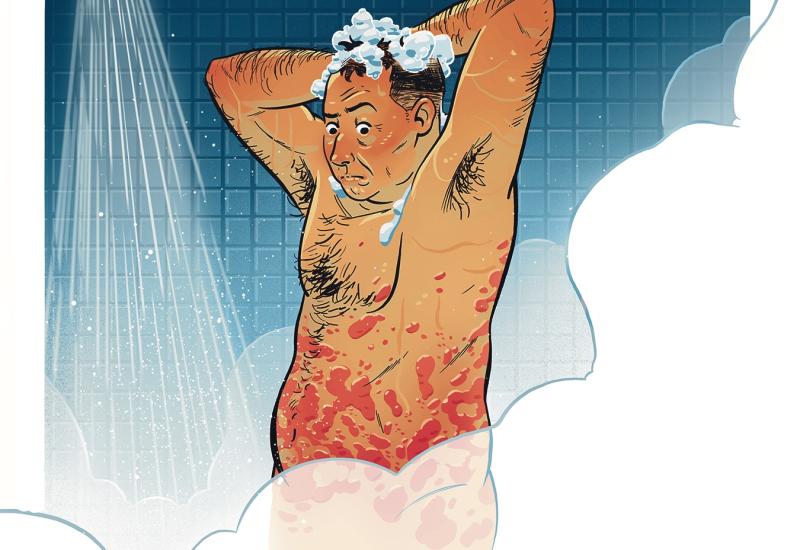

Miko MaciaszekIf you're showing signs of the bends, postpone your flight.

Todd was having a blast on his family vacation. He had made four dives the day before and planned to spend his last day in the Caribbean relaxing on the beach before flying home. But when he woke up that morning, Todd had joint aches and just didn’t feel well. The feeling got worse as the day progressed, but nothing seemed to help. He thought maybe he’d come down with a cold or the flu.

THE DIVER

An athletic 16-year-old in excellent health, Todd was a normal, active teen who played sports and spent time with his friends. He had been certified for only about a year and had made 10 lifetime dives before the vacation.

THE DIVES

On his first dive that morning, Todd spent 35 minutes in the ocean with a max depth of 50 feet and made a short safety stop. He took a 45-minute surface interval and then made a second dive to 30 feet with a two-minute safety stop. Five and a half hours later, Todd made his third dive to 50 feet for 35 minutes, but this time he didn’t make a safety stop at all. He stayed on the surface for only about 10 minutes — long enough to change his tank — before making his fourth and final dive to 50 feet for 30 minutes. This time he did make a three-minute safety stop. He didn’t report any problems during the dives and indicated he made normal ascents after each time.

THE ACCIDENT

The next morning, Todd woke up with mild joint aches, especially in his hands, knees, ankles and feet, and the pain increased as the day went on. He also had an uncomfortable feeling in his arms and legs, like a spreading numbness and tingling. Overall, he didn’t feel well. He said he had never experienced anything like this before, although he thought maybe he was getting sick. He spent most of his last day on vacation resting.

When Todd flew home with his family the following day, it had been a total of 42 hours since he finished his last dive, and 30 hours since he began feeling ill. The cabin pressure on the commercial flight was the equivalent of 6,000 feet of altitude. Todd couldn’t find a comfortable position in his seat. Nothing made him feel better and, on a scale of zero to 10, his pain actually increased from a 5 to a 7 or an 8. When the flight landed, his parents took him to the emergency room to be seen by a physician. The odd skin sensations were less noticeable by the time Todd saw the doctor, and his pain had returned to a 5, but both symptoms were still present. The physician who saw Todd had experience with dive accidents, and the local hospital had a hyperbaric chamber.

Todd was treated with a U.S. Navy Treatment Table 6 for about five hours. Though his pain improved, it did not completely resolve. The next morning, he was treated again in the chamber for two hours, but there was no change after the second treatment. His symptoms eventually dissipated over the following week with rest, and Todd eventually returned to normal.

ANALYSIS

While four dives in one day might sound like a heavy nitrogen load, it’s not uncommon. None of Todd’s dives was all that provocative, and he did not push no-decompression limits at any time. Todd didn’t complete a full safety stop for each dive, but his profile did not require him to. Unlike decompression stops, which are mandatory, safety stops are in place to add an extra margin of safety. If Todd had performed a dive with planned decompression, or if his computer had indicated that he had reached his no-decompression limit and skipped a safety stop anyway, it would be easy to suggest that his aggressive diving caused his decompression sickness (DCS). But that was not the case.

With every dive, there is a risk of DCS. (Most dive tables are designed with a 1 percent risk of DCS.) Divers sometimes use the term “undeserved hit” to refer to cases of DCS where there wasn’t an obvious reason, and this dive accident would probably fall into that category. The only way to completely avoid DCS is to stay out of the water.

In this case, there might be a physiological reason that led to Todd’s DCS. An example would be a birth defect like patent foramen ovale, which is a hole in the heart that should have closed after birth. However, diagnosing that condition requires an invasive test where air bubbles are injected into the blood stream at the heart. Few people are prepared to have this procedure.

The bigger issue in this situation is the ignorance of, or willfully ignoring, warning signs of DCS. Any time signs and symptoms of DCS appear after a recent history of diving — and without some other obvious explanation — you should consult a physician trained in diving medicine. (Typically, DCS symptoms manifest between six and 24 hours after diving.)

DAN’s Flying After Diving guidelines state that you should wait at least 12 hours after a single dive within no-decompression limits, or 18 hours after a series. Many people extend that out to 24 hours, just to build in an extra margin of safety. Once Todd began exhibiting symptoms of DCS, those travel guidelines flew out the window. He should have waited until the symptoms completely resolved — and then some — before boarding an aircraft. Dive physicians will often tell their patients to wait 72 hours after receiving a hyperbaric treatment, and being completely symptom-free, before flying.

LESSONS FOR LIFE

- Understand the signs and symptoms of decompression sickness so you can recognize them if you take a hit.

- If you suspect you might have DCS, alert the dive crew immediately. They can begin providing oxygen first aid to help your body begin clearing the nitrogen while alerting medical professionals.

- Don’t fly while symptomatic. Get evaluated by a physician trained in diving medicine to rule out DCS or to begin treatment.

- Perform safety stops to give your body a chance to remove built-up nitrogen.

More Lessons For Life:

Eric Douglas co-authored the book Scuba Diving Safety, and has written a series of adventure novels, children’s books, and short stories — all with an ocean and scuba-diving theme. Check out his website at booksbyeric.com.