Lemon Shark Nursery Study in Eleuthera, Bahamas

Shane GrossLemon shark pups in a tiny creek on Eleuthera Island in the Bahamas.

I love mangroves, except when i’m in them.

I’m being attacked by mosquitoes and sand flies while recovering from a mild jellyfish sting. It’s hot — like really hot. The sun is setting over tiny tide-driven Paige Creek on 110-mile-long Eleuthera Island, a beanpole strip of land located in the Atlantic east of Nassau. The sharks I’m here to photograph are not cooperating, so I decided to drag my camera gear (and my stiff, dehydrated body) back to the tent. I begin to fruitlessly swat at the sand flies that are getting into my (theoretically) sealed tent. While dripping salt water all over my sleeping bag, I check the images in the back of my camera, but they are not what I was hoping for. I dry off, lay back and wonder what the hell I’m doing here.

The goal is to capture images of baby lemon sharks. I saw 10 today, and call me crazy, but I find them super-cute! From a photographer’s perspective, they live in a beautiful habitat surrounded by mangrove trees. Sharks and trees are not things most people correlate, but these sharks depend on mangroves for the first five to eight years of their lives.

A week earlier, to learn more about lemon sharks, I traveled to the Cape Eleuthera Institute (CEI) and visited Ian Bouyoucos. A native New Yorker, Bouyoucos is a tall, young shark researcher whose primary interest is in elasmobranch stress physiology. Sharks’ lives are far more complex than the eating machines most of us conjure, says Bouyoucos. For example, he says, lemon sharks can form friendships. “Certain individuals tend to stay close to one another, and they can even learn from one another. They definitely have individual personalities.”

Related Reading: How Captive Breeding is Helping Shark Conservation

Shane GrossA 2-foot lemon shark pup looking for food off Eleuthera Island in the Bahamas.

From the moment they are born, sharks are independent. “They learn how to hunt for other juvenile prey and make a lot of mistakes,” explains Bouyoucos, “but they are learning.” Later, I am reminded of Bouyoucos’ comment as I watch shark pups accidentally bump into mangrove roots, get temporarily stuck in small spaces, and grab leaves in their mouths before spitting them back out as if to say, “Yuck!”

As you watch the 20-inch cuties swimming, the first thing you notice is how floppy they are — a far cry from the 10-foot-long powerful predators they will hopefully survive to become. Lemon sharks are currently listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN.

In a different part of the Bahamas, scientists at the Bimini Biological Field Station (aka Sharklab), led by Samuel “Doc” Gruber, recently made a stunning discovery: The lemon sharks there return to the same mangrove creek where they were born to give birth 12 to 15 years later. It took 20 years of tagging and monitoring to prove, and is the first time this behavior has been confirmed with any shark species.

Hence, every mangrove creek is important. I ask Bouyoucos what would happen if Paige Creek were turned into a marina. “If it’s developed, we don’t know what a returning mother would do, and the pups currently in the creek would certainly be displaced,” he tells me.

Like many shark species, lemons are caught in both commercial and sport fisheries for their meat, and their fins can generate high prices for shark-fin soup across the globe. Bouyoucos says their largest threat, however, “is habitat destruction; as mangroves disappear, so will lemon sharks.”

More than 50 percent of mangroves worldwide are already gone, and the Food and Agriculture Organization calculates the world is losing mangroves at a shocking rate of 1 percent per year. “People want to be by the ocean, so they build their homes or hotels, golf courses, etcetera, right where the mangroves are,” says Bouyoucos.

The good news is there are groups of people working hard to research, protect and restore mangroves. CEI is not only studying lemon sharks, but it is also reaching out to help educate the public. A scenic two-minute walk from CEI (a bridge over a mangrove creek, no less) is where you will find the Island School, which accepts international high school students who participate in CEI’s research. Locally, scientists from CEI visit all the schools on Eleuthera to talk about sharks, mangroves and many other aquatic topics that will affect their future. Internationally, many conservation organizations are working hard to help mangroves and the many species, including lemon sharks, that depend on them. There is still hope.

As I lie in my tent, uncomfortable, swatting away at an army of mosquitoes and sand flies, I know I want to help bring attention to the plight of these beautiful predators. I realize that I love mangroves, even when they are not so easy to love.

Related Reading: Why You Shouldn’t Feed Lionfish to Sharks

Shane GrossThe Cape Eleuthera Institute

Sustainable Study

The Cape Eleuthera Institute is a research station and educational facility teaching and housing students from around the world. In addition to the lemon shark study, researchers there are also doing pioneering work on deep-sea sharks, bonefish, inland ponds, lionfish and sea turtles. The institute is one of the most ecofriendly campuses in the world. They grow much of their own food, recycle cooking oil from cruise ships to power their boats and vehicles, store rainwater for showers (hot water provided by the sun) and toilets, and use solar and wind power for electricity.

Lemon Shark Facts

Lemon sharks grow to 10 feet (3 meters), but may only be 20 inches at birth.

It takes them 12-15 years to become mature.

The oldest recorded lemon shark is 37 years old; however, it is possible they live much longer.

They are found throughout the tropical and subtropical waters of Africa, Australia and the Americas.

They are known to congregate in large numbers for breeding, and give birth every second year. After the pups leave the mangroves, they can be found on reefs, estuaries, sea-grass beds, and have even been found up rivers, showing they can tolerate a range of salinities.

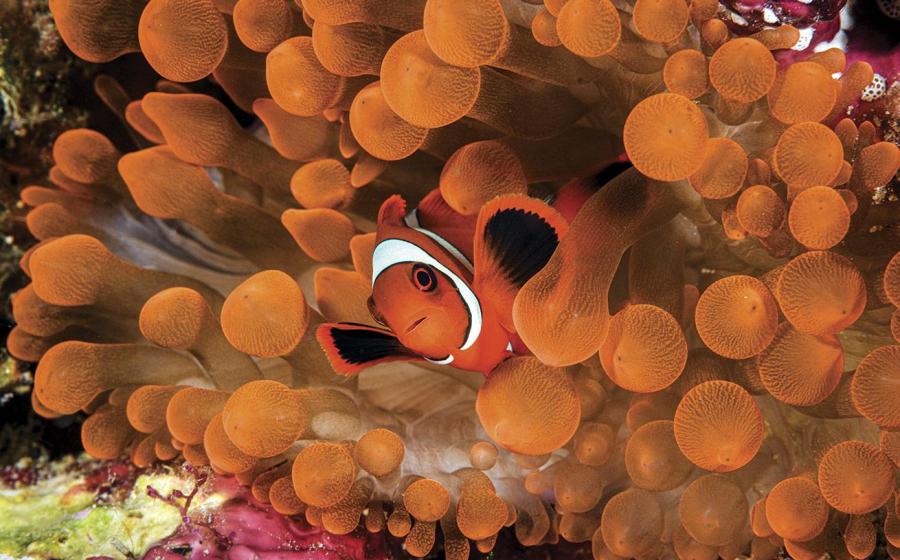

iStockphotoA pufferfish seen off Eleuthera Island, Bahamas

Mangrove Life

Lemon shark pups are not the only species to call the mangroves home. They share this thriving habitat with bonefish, barracuda, crabs, lobsters, rays, seahorses, puffers, snapper and grouper, among others. In some locations, like Florida and Cuba, alligators can also be found among the tangle of roots; overseas you might even find a tiger! It is always an adventure exploring mangroves, whether by snorkel, kayak or paddleboard.

Want to dive the Bahamas and around Eleuthera Island? Visit stuartcove.com.

Related Reading: 3 Nearshore Habitats to Dive