The Greatest Myths and Mysteries of the Underwater World

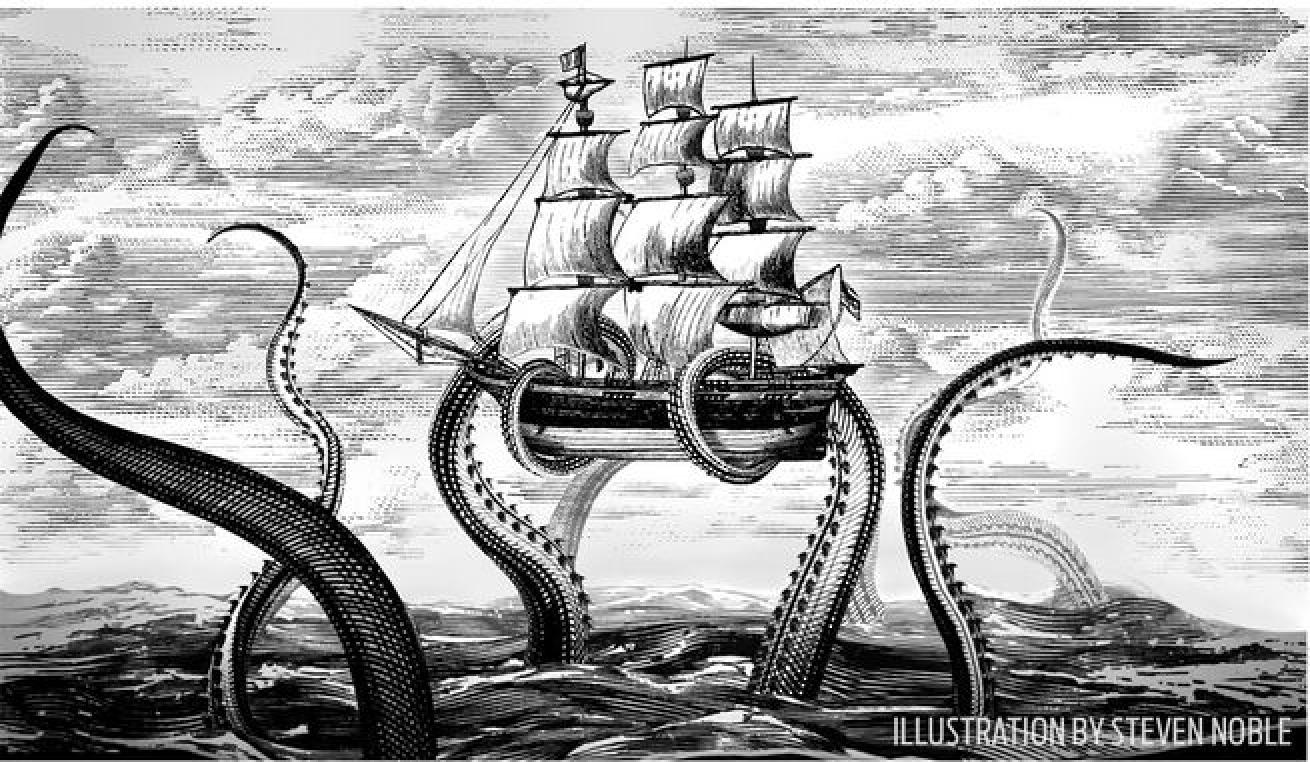

Steven NobleAn illustration of the Kraken

In the depths of the sea lurk mythological creatures and places that spark the imagination of writers, artists and filmmakers, but for some believers, these tall tales are not the stuff of fiction. For those who believe in cryptids — animals that stretch the limits of what is plausible — it’s an unshakeable conviction that they exist. The lake monster known as Nessie in Scotland’s Loch Ness, for example. There’s also the case of mistaken identity: sailors who confuse a homely dugong for a beautiful mermaid. And then there are the obsessive quests to locate the briny places of legend, such as Atlantis, or to prove the existence of supernatural forces in the Bermuda Triangle. The evidence? Eyewitness accounts, blurry photographs, and mysterious encounters and occurrences. Here, we delve into five far-fetched myths and how they came to be.

The Kraken

Rob Sorrenti & Owen Buggy PhotographyAn aerial view of the Kodiak Queen before it was sunk

First mentioned in a 13th-century Icelandic saga, the sea-dwelling kraken is a terrifying monster. It can reach the top of a sailing ship’s main mast, wrap its many tentacles around the hull and capsize it. The crew either drowned or were eaten by the fearsome colossus. With a beast like this awaiting sailors, it’s astonishing that early explorers ever left terra firma to venture out into the sea.

The kraken myth has its genesis in something that’s quite real — historians say the legend derived from sailors’ eyewitness accounts of the giant squid (Architeuthis sp). This species, which can reach 60 feet in length, is large enough to fight toothed leviathans such as sperm whales — and, it’s been reported, attack ships.

The kraken is from Norse mythology, a popular wellspring for science-fiction and fantasy-lit writers. In the first edition of Systema Naturae, a taxonomic classification of living organisms, Swedish botanist and zoologist Carl Linnaeus classified the kraken as a cephalopod (Microcosmus marinus). Though the creature was excluded from later editions, Linnaeus described it later as a “unique monster” that “is said to inhabit the seas of Norway,” though he admitted he had never seen one.

With its heart-attack-inducing appearance, the kraken stars in various films (Clash of the Titans), novels (China Miéville’s Kraken) and video games (Call of Duty: Ghosts). It’s the name given to the stomach-churning roller-coaster ride at SeaWorld. In a 2015 Geico commercial, a kraken emerges from a water hazard during a televised golf tournament. Its enormous tentacles snatch up a golfer and his caddy, whipping them this way and that, as one of the commentators whispers, “He’s definitely going to lose a stroke on this one.”

When a group of entrepreneurs in the British Virgin Islands wanted to add a touch of whimsy to a planned artificial reef — the YO-44, which survived the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor — they attached a massive krakenlike sculpture to it prior to the ship’s scuttling. The wreck, which was sunk in 65 feet of water off Virgin Gorda, is adorned with the rebar-and-mesh sculpture, including 80-foot tentacles guarding the deck.

“We wanted the site to capture people’s imagination,” says Andrew Devoy, of Virgin Management Ltd. “It’s thriving with life already.”

When asked what kind of marine life is settling on the wreck, Devoy reported that coral growth is sprouting and “juvenile squid are living in the kraken’s head.”

Of course they are.

Heritage Image Partnership LTD/AlamyFinished in 1901, A Mermaid was painted by John William Waterhouse, who was interested in the darker mythology of the mermaid as an enchantress.

Mermaids, Sirens and Sea Nymphs

“There is definitely something very appealing about the idea of a beautiful mythical creature that is part human and part fish, who lives under the sea, calling to sailors,” says professional mermaid Linden Wolbert, owner of Mermaids in Motion.

Historical accounts of mermaid sightings include one by Christopher Columbus, who was sailing near the Dominican Republic in 1493 when he saw three rising out of the water. He wrote in his diary that they’re “not half as beautiful as they are painted.” That’s because he wasn’t looking at Disney’s Ariel and her sisters; he had most likely spotted manatees.

In folklore, Disney’s romantic version of the undersea world of mer-people plays out a bit differently. Some regard the Assyrian goddess Atargatis — from 1000 B.C. — as the first mermaid. One version of the Atargatis myth has her falling in love with a shepherd, whom she accidentally killed. Wracked with grief, she flings herself into the ocean in an attempt to turn into a fish, thus drowning her sorrow and alleviating her guilt. Because of her beauty, though, she isn’t transformed completely. Instead, she becomes half goddess and half fish, with a tail below the waist and human body above.

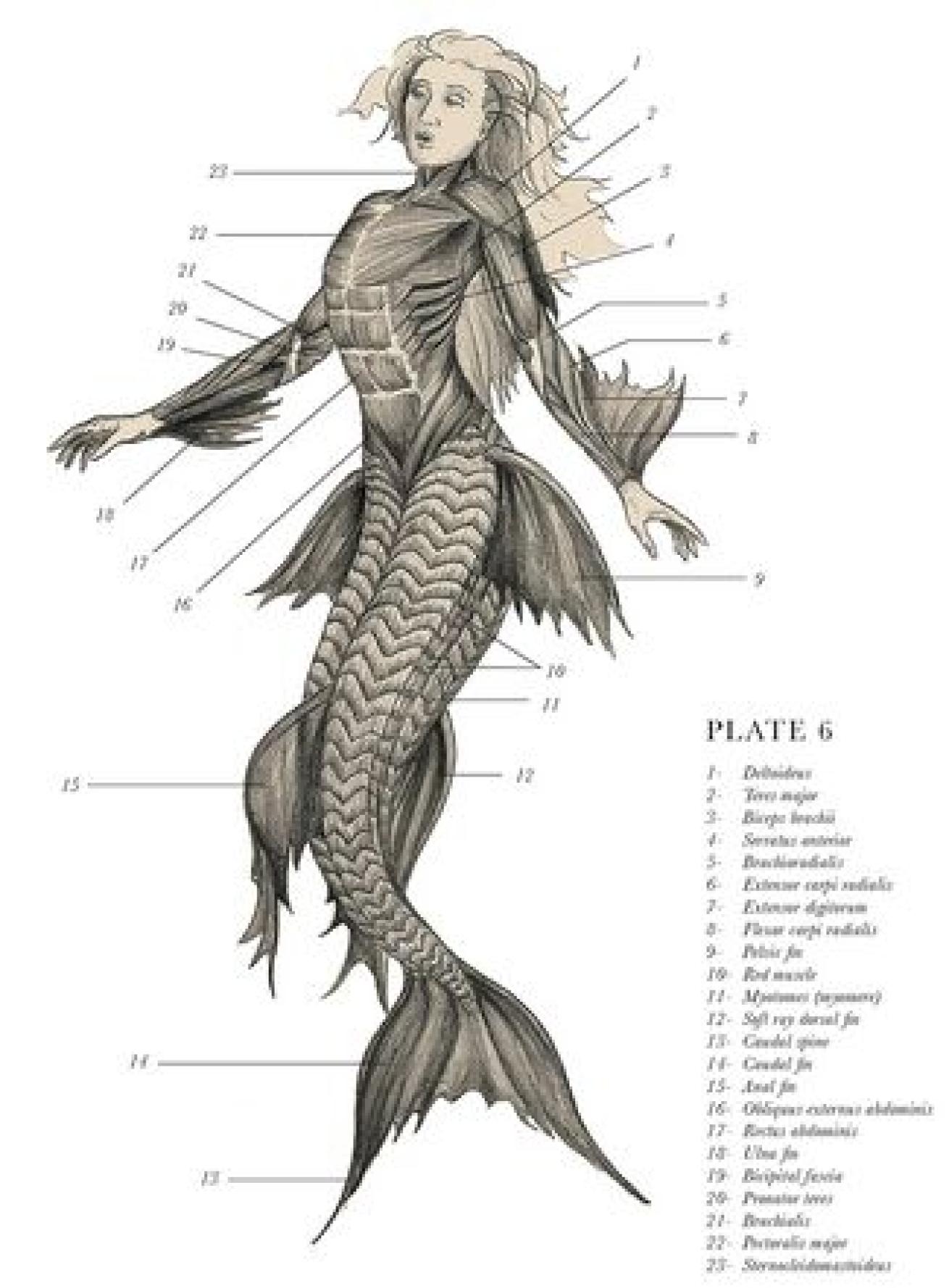

Illustration From The Resurrectionist By E.B. Hudspeth, ©2013 By Eric Hudspeth. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted With Permission Of Quirk Books, PhiladelphiaThe Resurrectionist by E.B. Hudspeth

The second part of this book is a fictional magnum opus: The Codex Extinct Animalia, a Gray’s Anatomy for mythological creatures — like the mermaid above — all rendered in meticulous anatomical detail.

In Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, published in 1837, there is no happily ever after. In fact, there’s very little happiness at all. The young mermaid doesn’t lose her voice, she loses her tongue, and after the prince leaves her for another woman, she dissolves into sea foam because she refuses to stab the prince and bathe in his blood. (Like many of Andersen’s fairy tales, the plot line is pretty gruesome.)

Other legends depict mermaids as vixens who seduce homesick sailors and drag them down to their underwater sea palaces. They cause storms and shipwrecks. They lure sailors to their death with their songs.

In Florida’s Weeki Wachee Springs, there are no storms, shipwrecks, seductions or sea goddesses, but professional female divers have performed as mermaids since 1947. The Sunshine State park calls itself “The Only City of Live Mermaids,” and though attendance is not what it was in the 1960s, when nearly 1 million tourists visited each year, you can still watch mermaids perform in an underwater stage with glass walls.

Wolbert fell in love with this version of mermaids as a young girl, after Disney released The Little Mermaid in 1989. “I suppose I was about 8 or 9 when the idea of mermaids really took hold,” says Wolbert. “I was obsessed with the movie. I knew every single line!”

Wolbert entertains the notion that mermaids might exist. “In a world where roughly 5 percent of our oceans has been explored and new species are discovered constantly, isn’t there a distinct possibility that these lovely creatures could be swimming beneath the surface?” she asks. “It’s an appealing thought to the landlubber

Atlantis

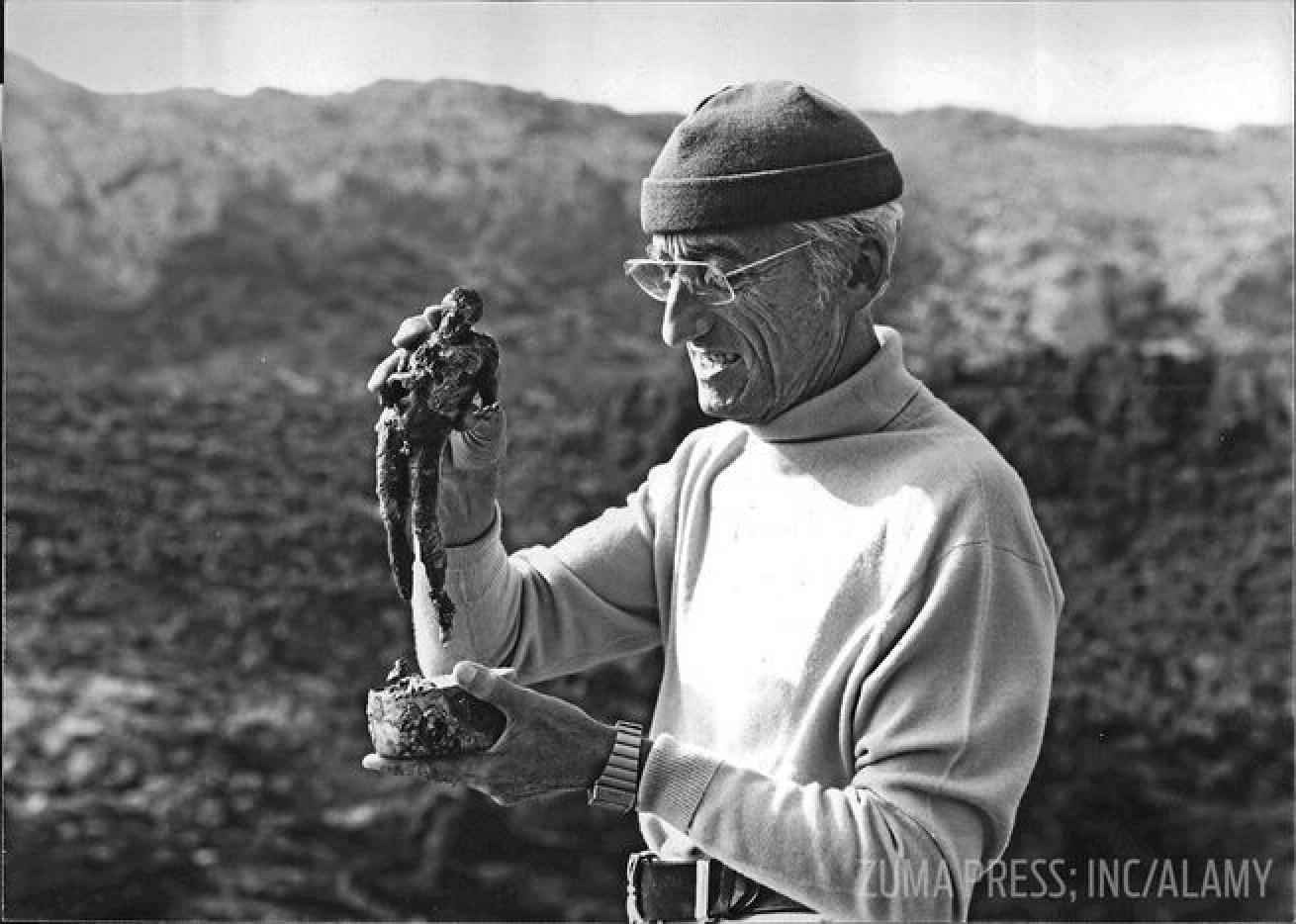

Zuma Press Inc./AlamyAfter searching the Aegean seabed off the Greek island of Santorini, in 1983, Jacques Cousteau said he found no evidence of Atlantis.

Remember Plato? He’s the ancient Greek dude who was taught by Socrates and who in turn taught Aristotle. He also penned an allegory that described the virtues of a Utopian island state called Atlantis. In the end, Plato wrote, Atlantis eventually fell out of favor with the gods, who delivered violent earthquakes and floods, causing the island to sink into the Atlantic Ocean. (The gods of ancient Greece could get a bit vindictive in the rarefied air of their cloud palace.)

Among all Plato’s contributions, Atlantis barely registers, but it figures prominently in literature, film and pop culture. Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea describes a visit to the sunken island aboard Capt. Nemo’s submarine Nautilus. Batman and Robin battle Nazis there (“Great Caesar!”), and the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles stumble upon it (and a character named Merdude). In “The Monkey Suit” episode of The Simpsons, Homer Simpson has a to-do list, which includes “Find, destroy Atlantis.”

The planet has a host of underwater sites that provoke debates over whether they’re man-made or natural, such as the Bahamas’ Bimini Road, Japan’s Yonaguni monument and the Baltic Sea anomaly. These sites give rise to speculation that beneath the waves lies evidence of once-thriving civilizations.

Fact or fiction? Consider this: In January 2017, geologists from Johannesburg, South Africa, published the results of a study that found 2 billion-year-old minerals under the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius; the scientists say it’s proof of a long-lost continent called Gondwana.

Loch Ness Monster

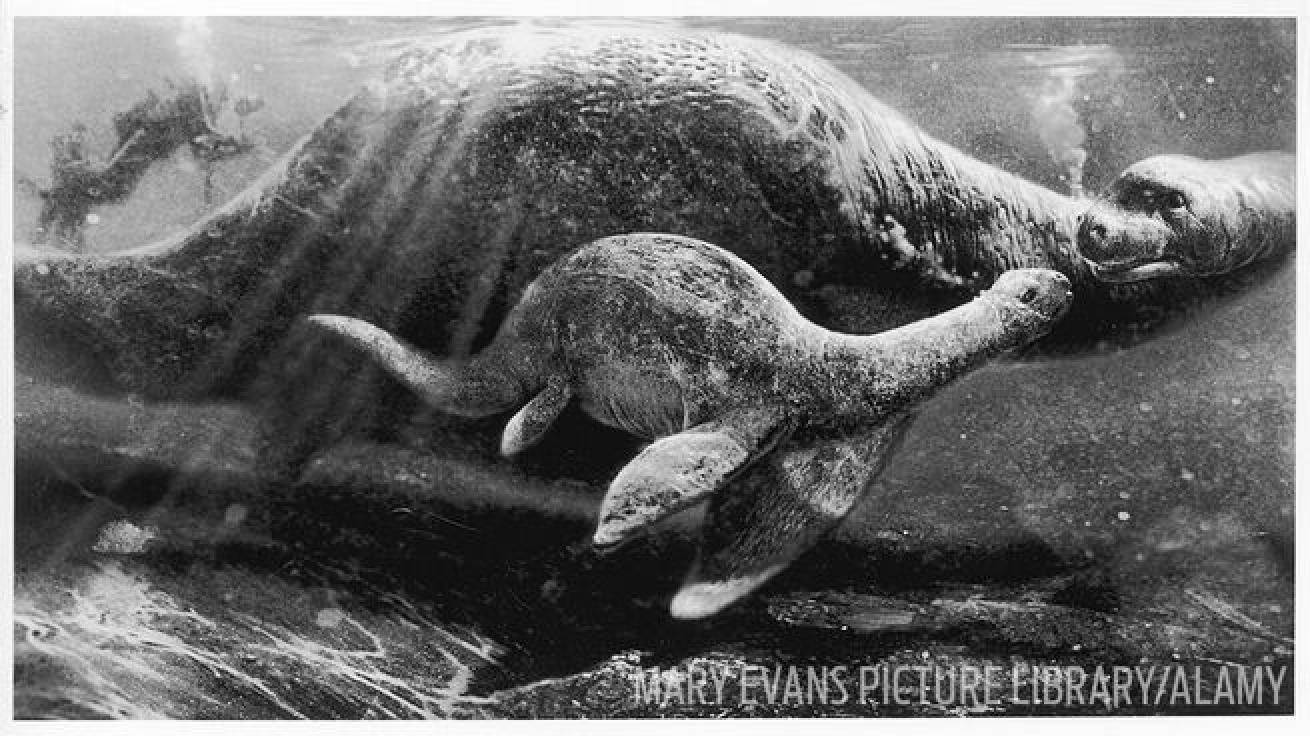

Mary Evans Picture Library/AlamyA photo of an unattributed painting of Nessie and her baby.

The locals living near Loch Ness in northwestern Scotland refer to the creature rumored to be living in the lake waters as Nessie. Depicted as resembling a plesiosaur, with a long neck and stubby, paddlelike fins, Nessie is the most famous of the world’s mythical lake creatures, which include Ogopogo (Okanagan Lake, British Columbia), Tahoe Tessie (California) and Mokele-mbembe (Mamfe Pool, Cameroon, Africa).

The scientific community treats Nessie the same way it regards spaceships from outer space, explaining sightings as hoaxes and the misidentification of marine creatures like otters.

But for the believers, Nessie might be elusive, but she is definitely real.

Related Reading: Cayman Brac and Little Cayman: Hidden Gems

AF Archive/AlamyReported to be of Nessie, this photo prank was initiated by someone who’d been humiliated by the Daily Mail. It’s actually a toy submarine; its head and neck were made from wood putty.

In 1934, a grainy photograph of Nessie was published in the Daily Mail. Credited to Robert Kenneth Wilson, a London physician — it was dubbed the “surgeon’s photograph” — the photo gave credence to the monster’s existence; it was declared an elaborate hoax in 1994. Wilson only delivered it to the newspaper.

But “Operation Deepscan” in 1987 served to fuel the fantasies of those who persist in seeking a creature that lurks deep in Loch Ness. Echo-sounder units indicated a large, moving object at a depth of 590 feet near Urquhart Bay.

Darrell Lowrance, whose company, Lowrance Electronics, donated the sonar devices, said: “There’s something here that we don’t understand, and there’s something here that’s larger than a fish, maybe some species that hasn’t been detected before.”

The Bermuda Triangle

Numerous ships and planes have vanished without a trace in a vast triangular swath of Atlantic Ocean loosely bound by Miami, Bermuda and Puerto Rico. (Cue the opening theme for the TV series The Twilight Zone.) Wild theories have accompanied the disappearances, from magnetic anomalies to alien abductions.

One of the disappearances in the so-called Bermuda Triangle involved five Grumman TBM Avenger torpedo bombers — collectively known as Flight 19 — that took off from the Naval Air Station in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, on the afternoon of December 5, 1945. Aboard the Avengers were 14 men. It began as a routine combat-training mission, but it ended with the aircraft and crew disappearing over the North Atlantic.

The plot thickened that evening. After the Navy lost radio transmission with Flight 19, two PBM Mariner “flying boats” were scrambled to search for the five planes, but 20 minutes after takeoff, one of the Mariners also vanished. That plane and its 13 crewmen were never recovered.

At the time, the term Bermuda Triangle hadn’t been invented. It was coined by Vincent Gaddis in an article he wrote about Flight 19, which was published by the pulp magazine Argosy in 1964.

Other losses in the Bermuda Triangle include USS Cyclops — in 1918, it and its crew of 309 went missing, the largest noncombat loss of life in U.S. Navy history — and in 2015, El Faro, a cargo ship with 33 on board.

While no one can say with 100 percent certainty what happened to these ships and aircraft, the losses were most likely due to human error, violent weather and mechanical failure.

Flight 19 was led by Lt. Charles Taylor, who became convinced that his compass was malfunctioning and ordered the planes to fly in the wrong direction. Worsening weather further disoriented the pilots. Taylor’s last radio transmission: “When the first plane drops below 10 gallons, we all go down together.”

As for the Mariner seaplane also lost that day, it likely suffered a fire and exploded.