ASK DAN: How Does Heart Health Impact My Diving?

Courtesy of DANMaintaining a healthy heart is essential to minimize the risk of complications while scuba diving.

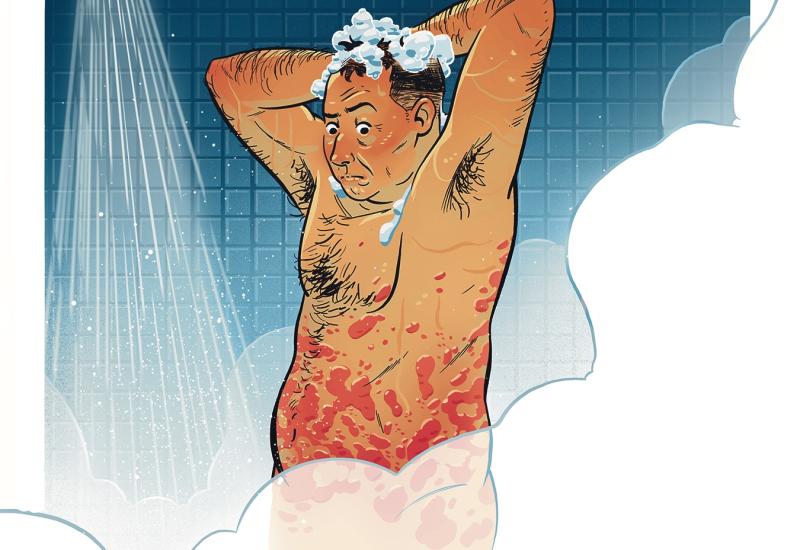

Scuba diving exposes you to many factors, including immersion, cold, hyperbaric breathing gas, elevated breathing pressure, exercise and stress, as well as a post-dive risk of gas bubbles circulating in your blood. Your heart’s capacity to support elevated blood output decreases with age and other risk factors. Having a healthy heart is of the utmost importance to your diving safety.

Coronary Artery Disease

Coronary atherosclerosis occurs when cholesterol and other material accumulating along the walls of the arteries of the heart, blocking blood flow. Many factors contribute to this condition: a high-fat, high-cholesterol diet, smoking, hypertension, increasing age and family history. Coronary artery disease is a leading cause of death worldwide. If you have coronary artery disease with symptoms, do not dive. Coronary artery disease diminishes delivery of blood—and therefore oxygen—to the heart. Exercise increases the heart’s need for oxygen. Depriving heart tissue of oxygen can lead to unconsciousness or a heart attack.

The classic symptom of coronary artery disease is chest pain, especially following exertion. Unfortunately, many people have no symptoms before they experience a heart attack. Older divers and those who have significant risk factors for coronary artery disease should have regular medical evaluations and appropriate studies such as exercise stress tests.

Hypertension

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is one of the most common medical conditions in divers. In the short term, people with hypertension have an elevated risk of a stroke due to the rupture of blood vessels in the brain. Long-term detrimental effects are more common; they include coronary artery disease, kidney disease, congestive heart failure, eye problems and cerebrovascular disease.

Mild hypertension may be controlled with diet and exercise, but medication is often necessary. If the diver’s blood pressure is under control, the main concerns should be the side effects of any medication they’re taking and evidence of any organ damage.

Most anti-hypertensive medications are compatible with diving as long as the side effects are minimal and the diver’s performance in the water is not significantly compromised. Regular examinations and screening for long-term consequences of hypertension are necessary. Any diver with longstanding high blood pressure should be monitored for secondary effects on the heart and kidneys.

Patent Foramen Ovale

The foramen ovale is an opening that exists between the right and left atria, the two upper chambers of the heart. During the fetal period, this opening is necessary for blood to bypass the circulation of the lungs (since there is no air in the lungs at this time) and go directly to the rest of the body. Within the first few days of life, this opening seals over, ending the link between these heart chambers. In approximately 25 to 30 percent of people, this opening persists and is called a patent foramen ovale (PFO).

A PFO can result in shunting of blood from the right side of the heart to the left side. Innocuous bubbles that may develop in the venous side of the circulation after a dive may be shunted to the left side of the heart and then distributed through the arteries. The result is that a paradoxical gas embolism or severe decompression sickness can result from a seemingly benign dive profile.

Studies of divers with severe decompression sickness have shown a rate of PFO higher than that observed in the general population. Special Doppler bubble contrast studies can identify a PFO. A diver with a known PFO should be aware of the potential increased risk of DCI. A diver with a PFO who has suffered an embolism or serious decompression sickness after a low-risk dive profile should likely refrain from future diving.

At present, most diving physicians agree that the risk of a problem associated with a PFO is not significant enough to warrant widespread screening of all divers. An episode of severe DCI that is not explained by the dive profile should initiate an evaluation for the existence of a PFO.

With more than 40 years of experience managing emergencies around the world, Divers Alert Network (DAN) helps ensure you are fully prepared—no matter where your adventures take you.

Learn more about the benefits of being a DAN member at dan.org.