Advanced Adventure: Exploring Egypt's Underwater Oases

Alexander the Great believed that Egyptian desert springs — oases that sheltered mystical oracles who would confirm his divinity, and his destiny — were connected underground. An international team of technical divers braves the Arab Spring to retrace his footsteps and test his theory.

A teenage boy wearing a shabby uniform and brandishing an AK-47 points us toward an abandoned shack. My pre-expedition training had taught me how to shoot this very rife, and how to identify whether there's a round in the chamber. More uniformed men with guns stumble out of the shed, wiping boredom from eyes that haven't seen a stranger in weeks. In the unforgiving and ruthless Egyptian desert, I’m hoping my Canadian smile and a box of dates will soothe the tension. I leave the negotiating to my guide, Fathi.

“In sha’Allah,” he says. We’re in God’s hands now.

Alexander the Great may have been the world’s first underwater explorer. Aristotle — Alexander’s tutor — described an early diving bell that Alexander used to explore the Mediterranean Sea in the 4th century B.C. Alexander’s device was “a very fine barrel made entirely of white glass,” which was towed out to sea and lowered into the water.

Alexander also may have been the first person to envision cave diving, and that’s what lured me on this dangerous adventure halfway around the world.

Marching an army from Cairo across the Great Sand Sea, Alexander’s mission was to consult the oracle at the Great Temple of Amun in Siwa, near the Libyan border. Many men died on his perilous journey, but Alexander was saved from starvation by a black crow that guided him through a blinding sandstorm. The oracle informed him that Alexander was the first true Pharaoh of Egypt and would go on to conquer the world.

The oracle itself is in fact a spring. Alexander’s prophet was a well inside the temple, and it was the water in that well that foretold his fate.

This parched desert landscape is dotted with verdant green oases. There are 200 springs in the immediate vicinity of Siwa, the nexus of five major historic caravan routes.

Cave divers know that water flowing from springs emanates from deep groundwater sources. Alexander suspected the springs in Siwa were connected, and that a person could swim from the temple to the nearby Mountain of the Dead.

That idea was irresistible to my explorer’s heart. What would we find? Would we discover ancient clues about temperature, rainfall and climate change? Would we find troves of artifacts telling the story of nomadic Bedouins? Was there life in oases springs?

There was only one way to find out.

By the time my proposal made it through approvals at National Geographic, the tumultuous Arab Spring was upon us. Egypt was in a dynamic, leaderless transition, and the country had descended into turmoil. Travel advisories warned of danger. Journalists were being detained, and sexual assaults on Western women in Cairo were reported in the news. The press desks in Cairo’s media offices were replaced with tripod-mounted machine guns. My nervous husband could not fathom why I wanted to go to Egypt at such a time.

But I have learned that news stories are not always accurate, and the reality of life on the ground can be warm and generous in even the most difficult situations. With my veteran technical diving colleagues Kevin Gurr and Phil Short, along with a small team of scientists and adventurers, we traveled across the world and through the sands of time. We faced fearful, suspicious adolescents armed with guns, and defused the tension with goodwill and bountiful gifts of food. It seems ironic that Google Earth should be my guide. My Bedouin chaperone, Fathi, of the Amazigh tribe, has no conception of the Internet and doesn’t know how to read two-dimensional maps. While he directs our travel based on ripples in the sand, I follow our GPS and printed sheets of satellite aerials.

“I’d like to find that lake near Tehbaghbagh. I think we need to turn east,” I muse. On my lap is an image of an enormous blue lake dotted with black spots that I believe are sinkholes. Fathi sighs and says that we cannot go there. “The route is impossible, in sha’Allah.”

Preventing us are decades-old land mines, miles of salt-mud quicksand, military check- points and high rock bluffs that mark the edge of the steep Qattara Depression. What I cannot understand from the images before me are the perils of a landscape that Fathi’s people know as well as the backs of their hands. Still, I want to try.

I simplify my request. “Fathi, please take me to all the places where there is water in the desert.”

What unfolded before us was a parched landscape that is reliant on the largest fossil aquifer on the planet. The Nubian Aquifer once held a tremendous volume of water, deep below Egypt, Libya, Chad and Sudan. But with only a scant rainstorm every 25 years or so, this precarious water supply may be doomed. Without replenishment, the fossil aquifer will eventually be drained. And without water, the ancient civilizations here will die.

We explore intricate Roman-built pools and irrigation canals that link the water supply to date-palm oases. We plunge into wells and bubbling springs, and find artesian geysers spewing water high into the air in the naked landscape. They tell a story of scarcity, and paint a picture of a life that can exist only in the presence and relative abundance of water. The people of Siwa, and other small oases, will survive only if the freshwater continues to flow.

In the 1980s, Russian oil prospectors drilled voraciously into the landscape around Siwa. They unleashed the power of the aquifer, rocketing high-pressure water jets into the sky. Disappointed with the results, they moved on, hoping to find black gold elsewhere.

Today, these uncapped wells continue to flow and spread water into the desert, creating enormous lakes that soon evaporate into hypersaline seas. The salty water, now useless for irrigation, continues to fill the desert and deplete this fragile resource.

After a difficult day of travel, we find ourselves near the edge of a great lake I was eager to explore. We’ll have to slog through mud and then swim a good distance, but nothing is going to stop me from reaching the headsprings and sinkholes we spotted on Google Earth.

Then we discover a hard fact that will prevent us from exploring any substantive caves: The flowing groundwater is 125°F, creating a nasty thermocline with the contrasting 50°F winter lake temperatures.

As we near the source, we are hit with blistering jets of scalding water, hazy thermoclines, and pulverizing mud and rocks emanating from the earth. Our sophisticated rebreathers and underwater camera equipment will do us little good — a simple snorkel is now the most important tool in my underwater exploration kit. We retreat, making tea from the boiling spring water, and dive back into our maps and imaginations, seeking more targets to explore.

The oracle at the Great Temple of Amun is actually a shallow, drying pool. It may have once linked to the Mountain of the Dead, but now a rock pile blocks access to any ancient caves or tunnels. The water is clean and satisfying but rapidly dwindling from the demands of encroaching development.

Perhaps this meager well in the distant desert is meant to remind us of humanity’s fate. We are not here to conquer the world as modern-day Alexanders, but rather to find and appreciate the desert’s most remarkable treasure — these precious pools of water.

The Chase Continues...

Unexplored caves in Turkey may yield the next clues in our quest for the oracle. Very few of the springs in Turkey have been explored by cave divers — even fewer have been visited by divers at all, yet they have yielded artifacts that are significant to history. A few miles from the coast of southern Turkey, the ancient site of Didyma is home to another natural spring that was visited by Alexander the Great. The goddess Leto

is reported to have spent “an hour of love” there with Zeus before giving birth to Artemis and Apollo; today, locals claim to have seen Leto swimming, bathing and rising out of springs situated in the ruins of Roman-era archaeological sites. Nestled among these ruins, clear water gushes from deep and bountiful sources near known caves at Kirkgoz springs and Burdur Insuyu Magarasi: prime targets for future exploration.

Alexander the Great believed that Egyptian desert springs — oases that sheltered mystical oracles who would confirm his divinity, and his destiny — were connected underground. An international team of technical divers braves the Arab Spring to retrace his footsteps and test his theory.

Jill HeinerthChasing the Oracle

Unveiling secrets of Egypt's western desert meant venturing into many caves — above and below the ground.

A teenage boy wearing a shabby uniform and brandishing an AK-47 points us toward an abandoned shack. My pre-expedition training had taught me how to shoot this very rife, and how to identify whether there's a round in the chamber. More uniformed men with guns stumble out of the shed, wiping boredom from eyes that haven't seen a stranger in weeks. In the unforgiving and ruthless Egyptian desert, I’m hoping my Canadian smile and a box of dates will soothe the tension. I leave the negotiating to my guide, Fathi. “In sha’Allah,” he says. We’re in God’s hands now.

Jacqueline WindhAuthor Jill Heinerth

Explorer Jill Heinerth sips tea topside while exploring Egypt's Siwa Oasis.

Jacqueline WindhBlue Hole

Jill Heinerth and Phil Short peer into a blue hole near Siwa Oasis.

Alexander the Great may have been the world’s first underwater explorer. Aristotle — Alexander’s tutor — described an early diving bell that Alexander used to explore the Mediterranean Sea in the 4th century B.C. Alexander’s device was “a very fine barrel made entirely of white glass,” which was towed out to sea and lowered into the water.

Alexander also may have been the first person to envision cave diving, and that’s what lured me on this dangerous adventure halfway around the world.

Jill HeinerthOn the Hunt

Dr. Jacqueline Windh examines a map to improve her understanding of Siwa's surficial geology.

Marching an army from Cairo across the Great Sand Sea, Alexander’s mission was to consult the oracle at the Great Temple of Amun in Siwa, near the Libyan border. Many men died on his perilous journey, but Alexander was saved from starvation by a black crow that guided him through a blinding sandstorm. The oracle informed him that Alexander was the first true Pharaoh of Egypt and would go on to conquer the world.

The oracle itself is in fact a spring. Alexander’s prophet was a well inside the temple, and it was the water in that well that foretold his fate.

This parched desert landscape is dotted with verdant green oases. There are 200 springs in the immediate vicinity of Siwa, the nexus of five major historic caravan routes.

Cave divers know that water flowing from springs emanates from deep groundwater sources. Alexander suspected the springs in Siwa were connected, and that a person could swim from the temple to the nearby Mountain of the Dead.

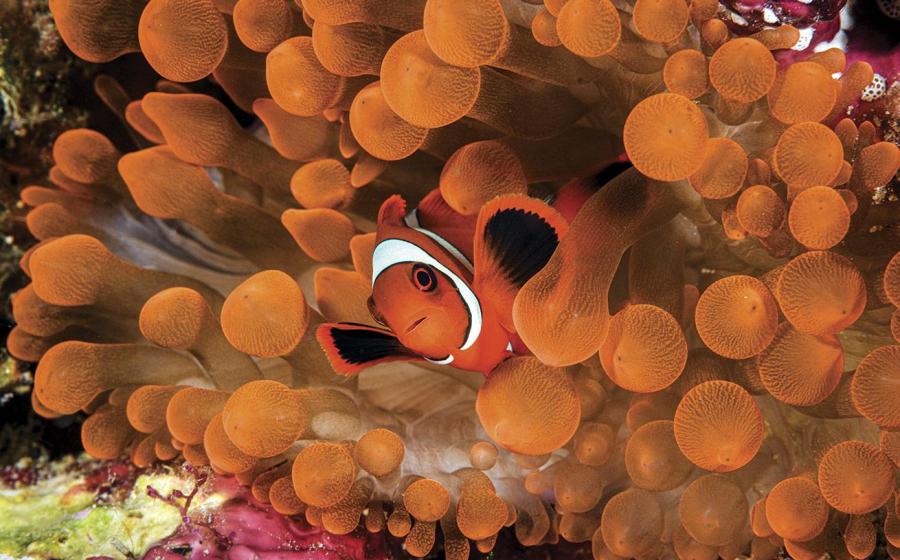

That idea was irresistible to my explorer’s heart. What would we find? Would we discover ancient clues about temperature, rainfall and climate change? Would we find troves of artifacts telling the story of nomadic Bedouins? Was there life in oases springs?

There was only one way to find out.

Jill HeinerthAlexander the Great and the Oracle at Siwa

Oracles in antiquity were believed to see into the future, and were consulted before any momentous occasion or decision. The oracle at Siwa (pictured) was well known across the ancient world, particularly in Greece. Alexander the Great, a Macedonian by birth, made the difficult trek in 331 B.C. — it’s believed he sought confirmation that he was a son of the god Zeus, who was associated with the Egyptian god Amun; a “yes” would give Alexander legitimacy as ruler of Egypt, which he had recently conquered. But the oracle went much further: According to legend, it confirmed that he would one day conquer the known world. Did the oracle also foretell his early death, in 323 B.C., at age 32? No one will ever know, because Alexander was accorded the unique privilege of hearing from his oracle directly, and not through a priest, as was common.

By the time my proposal made it through approvals at National Geographic, the tumultuous Arab Spring was upon us. Egypt was in a dynamic, leaderless transition, and the country had descended into turmoil. Travel advisories warned of danger. Journalists were being detained, and sexual assaults on Western women in Cairo were reported in the news. The press desks in Cairo’s media offices were replaced with tripod-mounted machine guns. My nervous husband could not fathom why I wanted to go to Egypt at such a time.

But I have learned that news stories are not always accurate, and the reality of life on the ground can be warm and generous in even the most difficult situations. With my veteran technical diving colleagues Kevin Gurr and Phil Short, along with a small team of scientists and adventurers, we traveled across the world and through the sands of time. We faced fearful, suspicious adolescents armed with guns, and defused the tension with goodwill and bountiful gifts of food. It seems ironic that Google Earth should be my guide. My Bedouin chaperone, Fathi, of the Amazigh tribe, has no conception of the Internet and doesn’t know how to read two-dimensional maps. While he directs our travel based on ripples in the sand, I follow our GPS and printed sheets of satellite aerials.

Jill HeinerthThe Team

The exploration team pictured with some of their means of exploring the oasis.

“I’d like to find that lake near Tehbaghbagh. I think we need to turn east,” I muse. On my lap is an image of an enormous blue lake dotted with black spots that I believe are sinkholes. Fathi sighs and says that we cannot go there. “The route is impossible, in sha’Allah.”

Preventing us are decades-old land mines, miles of salt-mud quicksand, military check- points and high rock bluffs that mark the edge of the steep Qattara Depression. What I cannot understand from the images before me are the perils of a landscape that Fathi’s people know as well as the backs of their hands. Still, I want to try.

I simplify my request. “Fathi, please take me to all the places where there is water in the desert.”

Jill HeinerthWell Exploration

Reaching for his camera, Phil Short explores a desert well.

What unfolded before us was a parched landscape that is reliant on the largest fossil aquifer on the planet. The Nubian Aquifer once held a tremendous volume of water, deep below Egypt, Libya, Chad and Sudan. But with only a scant rainstorm every 25 years or so, this precarious water supply may be doomed. Without replenishment, the fossil aquifer will eventually be drained. And without water, the ancient civilizations here will die.

We explore intricate Roman-built pools and irrigation canals that link the water supply to date-palm oases. We plunge into wells and bubbling springs, and find artesian geysers spewing water high into the air in the naked landscape. They tell a story of scarcity, and paint a picture of a life that can exist only in the presence and relative abundance of water. The people of Siwa, and other small oases, will survive only if the freshwater continues to flow.

In the 1980s, Russian oil prospectors drilled voraciously into the landscape around Siwa. They unleashed the power of the aquifer, rocketing high-pressure water jets into the sky. Disappointed with the results, they moved on, hoping to find black gold elsewhere.

Today, these uncapped wells continue to flow and spread water into the desert, creating enormous lakes that soon evaporate into hypersaline seas. The salty water, now useless for irrigation, continues to fill the desert and deplete this fragile resource.

Jill HeinerthIrrigation Canal

An irrigation canal moves groundwater from an oasis in Egypt.

After a difficult day of travel, we find ourselves near the edge of a great lake I was eager to explore. We’ll have to slog through mud and then swim a good distance, but nothing is going to stop me from reaching the headsprings and sinkholes we spotted on Google Earth.

Then we discover a hard fact that will prevent us from exploring any substantive caves: The flowing groundwater is 125°F, creating a nasty thermocline with the contrasting 50°F winter lake temperatures.

As we near the source, we are hit with blistering jets of scalding water, hazy thermoclines, and pulverizing mud and rocks emanating from the earth. Our sophisticated rebreathers and underwater camera equipment will do us little good — a simple snorkel is now the most important tool in my underwater exploration kit. We retreat, making tea from the boiling spring water, and dive back into our maps and imaginations, seeking more targets to explore.

Jill HeinerthMountain of the Dead

Here you can see an intricately painted tomb in Siwa's Mountain of the Dead.

Brenda WeaverAn Abu Shrouf Spring

Here, you can see an illustration of a typical spring in Abu Shrouf.

The oracle at the Great Temple of Amun is actually a shallow, drying pool. It may have once linked to the Mountain of the Dead, but now a rock pile blocks access to any ancient caves or tunnels. The water is clean and satisfying but rapidly dwindling from the demands of encroaching development.

Perhaps this meager well in the distant desert is meant to remind us of humanity’s fate. We are not here to conquer the world as modern-day Alexanders, but rather to find and appreciate the desert’s most remarkable treasure — these precious pools of water.

The Chase Continues...

Unexplored caves in Turkey may yield the next clues in our quest for the oracle. Very few of the springs in Turkey have been explored by cave divers — even fewer have been visited by divers at all, yet they have yielded artifacts that are significant to history. A few miles from the coast of southern Turkey, the ancient site of Didyma is home to another natural spring that was visited by Alexander the Great. The goddess Leto is reported to have spent “an hour of love” there with Zeus before giving birth to Artemis and Apollo; today, locals claim to have seen Leto swimming, bathing and rising out of springs situated in the ruins of Roman-era archaeological sites. Nestled among these ruins, clear water gushes from deep and bountiful sources near known caves at Kirkgoz springs and Burdur Insuyu Magarasi: prime targets for future exploration.

Jill HeinerthDiscovering Abu Shuruf: A

Located 20 miles east of Siwa, the Abu Shuruf spring is a source of precious water for the local villagers of Az-Zaytun, as well as being a popular swimming hole. During Roman times, a stone wall was built around an artesian spring that discharges warm water from a boulder pile in the pool’s center.

Jill HeinerthDiscovering Abu Shuruf: B

Roughly 15 feet deep, Abu Shuruf spring also has a sand boil at its bottom. An underwater doorway allows water to flow into an irrigation canal (pictured), which has a solid floor and walls. The same irrigation system is used in a number of springs found in the Siwa area.

Courtesy Google (Google Earth Pro)Find Your Own Oracle

On Feb. 1, 2015, Google opened one of its most powerful apps — Google Earth Pro — to the universe. For a decade, businesses, scientists and hobbyists from all over the world have been using Google Earth Pro for everything from exploring remote regions to placing 3-D architectural models in cityscapes. For everyday divers, Google Earth Pro can help you measure, visualize and record HD simulations of flyovers to your next dive destination. To play with Google Earth Pro, or to just have fun flying around the world, grab a free access key and download Google Earth Pro today.