8 Wrecks With Fascinating Backstories

^^T^^hese are the backstories of some of the best-loved wreck dives on the planet, from the Red Sea to the Caribbean, Hawaii and Australia, from tragedies that cost dozens of lives to the glamorous world of a sailing ship and its Hollywood casting call. Knowing their histories will surely tempt you to plan some dives, but it also might influence how you go about making those plans, if you’re lucky enough to submerge on any or all. So sit back, soak up these stories and dive tips, and get ready to plan the wreck dives of your life.

Damien MauricPart of Thistlegorm’s enduring appeal is the vast array of material still to be examined in its holds.

The Ship: Thistlegorm (Red Sea)

Depth: 52 to 105 feet

Visibility: 30 to 90 feet

Water Temp: 68 degrees F in winter; lower 80s in the summer

Dive Tip: The wreck is in a remote area where strong currents are common.

Heralded as the most popular wreck in the world, 415-foot steamship Thistlegorm was launched in June 1940. When called to war, a 4.7-inch antiaircraft gun and a heavy-caliber machine gun were added to its stern.

Its fourth and final voyage was a delivery from Scotland to British soldiers in North Africa — every inch filled with boots, rifles, motorcycles, locomotives and more.

According to online shipwreck database Wrecksite, instead of journeying through the Mediterranean and attracting German U-boats, the ship’s convoy took a route around Africa.

When they finally reached the Suez Canal, a collision had closed the entrance. For two weeks, the ships waited at a spot designated as safe — as it turned out, Thistlegorm would be waiting 77 years and counting.

The Sinking

On October 5, 1941, the Luftwaffe dispatched planes to bomb a transport vessel (probably the Queen Mary) but were unable to find it. On return, one plane spotted the anchorage and targeted the largest ship it saw: Thistlegorm. The plane dropped two bombs, their impact magnified by the ammunition on board, which resulted in an explosion that ripped the ship in half and sent two locomotives flying. Thistlegorm sank quickly and suffered nine casualties out of 42 men aboard.

The death toll would likely have been higher had it not been for warm weather — many crew members were sleeping on deck.

The Dive

Thistlegorm was filmed by Jacques-Yves Cousteau in 1955, but it didn’t become a wreck-diving destination until the ’90s.

Broken in two, the wreck lies on its port side at 105 feet. (The bow is shallower, about 52 feet.)

At the stern is the ship’s gigantic propeller as well as two antiaircraft guns. The impact site and former cargo reveal Mark II Bren Carrier Tanks tossed like playthings, spilled crates of munitions, rubber boots and other artifacts.

Forward of Thistlegorm’s fatal wound are three intact holds filled with grenades, mines, munitions, Morris cars, Bedford trucks, motorbikes, Enfield carbines, artillery, and so much more.

On deck sights include the captain’s cabin and bridge, the anchor winch, and the tank and railway cars that were intended to run behind the locomotives, now lying on the seafloor off to either side of the wreck.

Greg Piper; Charo GertrudixA 2017 storm pushed Kittiwake over on its side; its recompression chambers and interior sights are popular with divers.

The Ship: Kittiwake (Cayman Islands)

Depth: 27 feet to 75 at the sand

Visibility: Upwards of 100 feet

Water Temp: High 70s in winter; low to mid-80s in summer

Dive Tip: Kittiwake is a private park and requires a $10 admission fee per dive.

The USS Kittiwake, a Chanticleer-class submarine rescue ship, is one of the best-known dives in the Caribbean. The 251-foot 2,200-ton ship launched July 10, 1945, and escorted submarines during maneuvers where its crew practiced underwater-rescue procedures.

Kittiwake had a storied career before it became a destination. It assisted USS George Washington during the first successful firing of a Polaris missile from an under-water sub on July 20, 1960, off Cape Canaveral, Florida.

Many of Kittiwake’s exploits are still classified, but some tales have come to light via All Hands, the magazine of the U.S. Navy. Clyde M. Prickett set an open-water deep-diving record from Kittiwake, to a depth of 501 feet in Panama Bay in April 1949. Its crew recovered the space shuttle Challenger’s black box from the bottom of the Atlantic in 1986.

Kittiwake was decommissioned in 1994 and mothballed to Norfolk, Virginia. It would wait eight years before being called to service again.

The Sinking

When the Cayman Islands decided to add a wreck, they contacted the United States Maritime Administration (MARAD), which donates derelict vessels for use as artificial reefs.

The Cayman Islands got the title for Kittiwake in August 2009. The preparation was daunting; in addition to being made environmentally friendly, Kittiwake was also made more dive-friendly, with holes cut in its hull, and many of its doors, hatches, bulkheads and some floors removed. On January 5, 2011, Kittiwake went down 800 yards off Seven Mile Beach.

The Dive

The vessel sits in shallow water, allowing plenty of bottom time: Highlights include the mess hall, massive propellers and towering smoke stack, two recompression chambers, and a head complete with an intact mirror. The wheelhouse had its panels removed after being damaged by a storm in 2017. Scuba divers can still pose at the wheel, which now feels like driving the world’s largest convertible. Open water divers are limited to the first three decks; those with advanced certifications can explore all five.

Peppermint shrimp, arrowhead crabs, fireworms and banded coral shrimp can be found all over. Garden eels make themselves at home in the sands, attracting stingrays and eagle rays. Barracuda, horse-eye jacks, turtles and grouper also hang around.

Douglas J. HoffmanMaui’s Carthaginian II, pictured here in 2011, is a replica of a replica.

The Ship: Carthaginian II (Hawaii)

Depth: 97 feet

Visibility: 100 feet or more

Water temps: 75 to 82 degrees F

Dive Tip: Atlantic Adventures submarines visit the wreck; give the tourists a wave.

Carthaginian was a replica whaleship — actually two — and museum in Lahaina, Hawaii, on the island of Maui. Today those who wish to travel back in time must first travel below.

The first ship was a three-masted schooner built in Denmark in 1921, a 130-foot cargo hauler with a beam of 22½ feet. Eventually it ended up in San Diego, and in 1965 underwent a hasty transformation to the Carthaginian, the square-rigged whaling bark in James Michener’s Hawaii, and then sailed to Hawaii for filming.

Eventually the Lahaina Restoration Foundation purchased the ship, which was taken out periodically by a volunteer crew. It foundered on its way to dry dock in Honolulu on Easter Sunday 1973, and was lost with no casualties.

The Sinking

The foundation was quick to find a replacement in a 93-foot German-made schooner, transformed into a two-masted brig rechristened Carthaginian II. That ship would spend three decades educating guests, but it became too costly to maintain. In 2003, Carthaginian II became a purpose-sunk artificial reef off Puamana Beach Park.

The Dive

Carthaginian II sits at 97 feet on sand, appropriate for beginner and intermediate divers. The masts have collapsed; divers can swim through the large hold. The engine room and forward compartment are closed off, but scuba divers can peer in through the bars.

Brandon ColeYongala lay undisturbed and unidentifed for nearly 40 years after it disappeared in 1911.

The Ship: Yongala (Australia)

Depth: 52 to 98 feet

Visibility: 30 to 80 feet

Water Temp: Mid-70s to mid-80s

Dive Tip: Access is by permit; use a licensed operator.

Around March 23, 1911, luxury passenger steamship SS Yongala sank en route to Townsville, Australia, during a cyclone. The ship disappeared with no survivors; its final resting place remained unknown for decades. It has since earned a reputation as the largest and most intact wreck for divers in Australia.

The 350-foot luxury passenger ship built in England in 1903 was named after an Aboriginal word for “broad water.” It spent its brief life ferrying travelers around the Australian continent, one of the farthest-ranging such vessels of its day.

The Sinking

On March 14, 1911, Yongala unloaded 50 tons of cargo and secured more in its hold — including a racehorse named Moonshine — after it arrived in MacKay. In addition, Yongala carried 49 passengers and 73 crew when it departed March 23. But instead of ferrying those 122 souls to Townsville, it would bring them to an early grave.

While Yongala was still in sight of land, the local telegraph operator received warning of a cyclone. He sent flag and wireless signals, but Yongala did not see the flags and had not yet received the wireless equipment ordered for it.

The last sighting of Yongala was approximately five hours later at Dent Island. A lighthouse keeper watched as it steamed into Whitsunday Passage in worsening weather. A search was soon underway, but Yongala would not be seen again for nearly 40 years — according to the Townsville Maritime Museum, the only body ever found was Moonshine.

The Dive

Yongala was discovered at the beginning of World War II when a minesweeper fouled an obstruction in shipping lanes. In 1947, HMAS Lachlan stopped to conduct an investigation of the object.

Lachlan determined it was most likely a shipwreck, believed to be the long-lost Yongala, although no effort was made to ID the ship for 11 more years.

Today Yongala sits inside the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park 48 nautical miles from Townsville, resting on a sandy bottom with a slight list to starboard. The ship’s superstructure remains intact, although some decks have fallen off. Yongala is protected; penetration is forbidden. Its isolation has made it a magnet for marine life, from soft corals and swarms of tropical fish to giant trevally and schools of barracuda. Sea turtles, sharks, sea snakes and mantas are common.

The Ship: Bianca C (Grenada)

Depth: 90 to nearly 167 feet

Visibility: 60 to 180 feet

Water Temps: 79 to 86 degrees F

Dive Tip: Due to current and depth, you likely won’t get more than 10 or 15 minutes on the wreck.

At almost 600 feet, Bianca C is the largest divable wreck in the Caribbean. The luxury cruise ship was begun in France in 1939 but was interrupted by the outbreak of WWII. Eventually the ship, then called La Marseillaise, was completed in 1949, accommodating 341 first-class passengers, 75 tourist-class passengers and 371 economy-class passengers. Its interior was inspired by Saigon, Vietnam, one of the stops on its initial itinerary, according to the blog Cruise Line History. After a series of ownership and name changes, the ship landed with the Costa Line in 1959 and was rechristened Bianca C, serving from Naples, Italy, to Venezuela.

The Sinking

Bianca C departed on its final voyage October 12, 1961. Ten days later, an explosion in the main boiler room spread fire throughout the ship. Residents of St. George’s, Grenada, sprang into action with a flotilla that rescued 672 people. One crewman was lost in the explosion; two later died of burns.

Bianca C was anchored in shipping lanes. When British frigate Londonderry arrived two days later, its crew boarded the still-flaming ship to attach tow lines. Londonderry attempted to beach the liner off Point Salines, but the tow line broke. On October 24, Bianca C slipped below.

The Dive

The ship rests about a mile off Grenada’s southwestern shore at 167 feet, upright on its keel, its top reaching around 90 feet. This wreck is typically done as a drift dive with a negative entry. Broken-up decks create an alien landscape with glimpses of walkways and railings below. Structural integrity is a growing concern; penetration is not recommended.

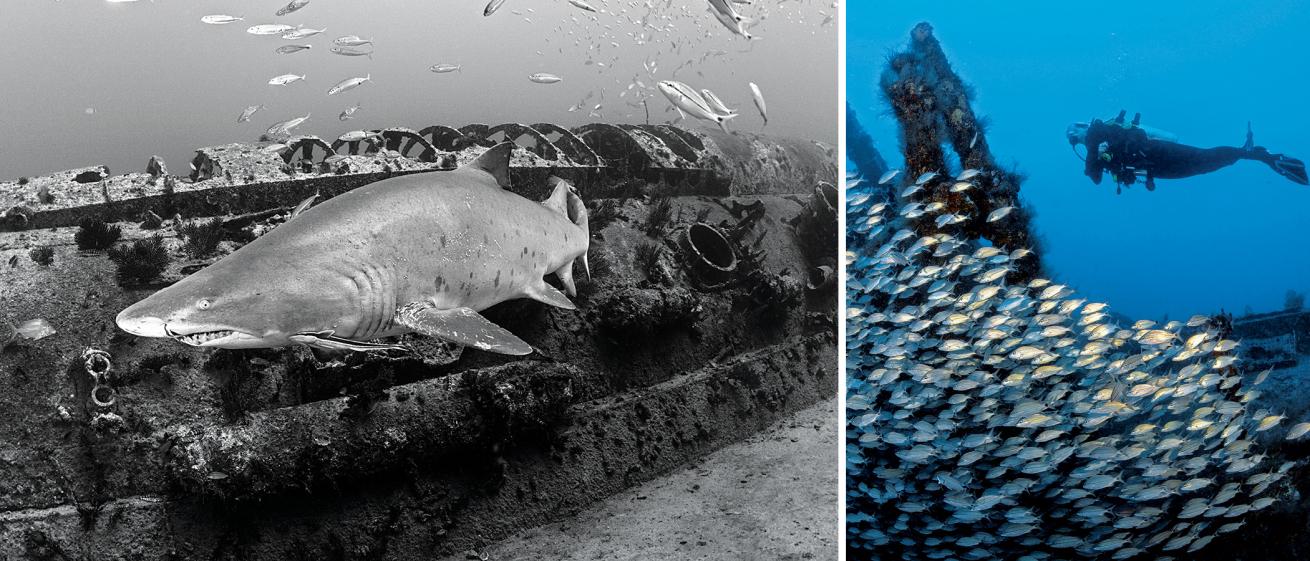

Mike Gerken; Stocktrek Images Inc./AlamyIt’s hard to say what’s more popular with divers: the U-352 or the sand tiger sharks that frequent the submarine.

The Ship: U-352 (North Carolina)

Depth: 90 to 110 feet

Visibility: 40 to 70 feet

Water Temp: 50 to 55 degrees F in winter; high 70s to low 80s in summer

Dive Tip: U-352 is a war grave; it is illegal to penetrate the wreck or remove artifacts.

German U-boats prowled the U.S. coast during World War II, looking for unwary ships. U-352 was one such boat, but in the end, its only addition to North Carolina’s Graveyard of the Atlantic was itself.

According to database uboat.net, U-352 was launched May 7, 1941. U.S. Navy records show it carried an 8.8 cm cannon, a 2 cm antiaircraft gun and 14 torpedoes during its last cruise, under the command of Hellmut Rathke, a stern disciplinarian. One of the sub’s surviving crewman later told the Discovery Channel that Rathke was obsessed with receiving a Knight’s Cross medal for sinking 100,000 tons of enemy ships, a reckless obsession that would doom his boat.

U-352 left for the United States at the beginning of April 1942, under threat from patrolling aircraft. Once it was spotted and had two bombs dropped on it, but it escaped without damage. During their later interrogation, crewmen said they were able to tune in to American radio programs; they liked jazz.

The SInking

Despite firing seven or eight torpedoes during its cruise, U-352 did not sink a single ship. Around 4 p.m. on May 9, the crew came across what it thought was a merchant vessel; Rathke ordered a torpedo. Unfortunately for the Germans, it missed. The ship they had fired on was not a merchant ship but Coast Guard Cutter Icarus. Realizing his mistake, Rathke brought his boat to the seafloor. But 95 feet wasn’t deep enough to avoid the immediate barrage of depth charges. The periscope and conning tower suffered major damage, and lights failed. Rathke gave the order to abandon the sub. When it returned to the surface, Icarus opened fire. Five minutes after resurfacing, U-352 returned to the bottom of the Atlantic for good. Thirteen crewmen died, plus another later of his injuries. Survivors were taken to Charleston, South Carolina, as prisoners of war.

The Dive

U-352 was identified in 1975 when George Purifoy, founder of Olympus Dive Center in Morehead City, North Carolina, pinpointed the lost sub 26 miles south of town.

The 218-foot-long wreck sits upright with a 45-degree starboard list. The outer hull has deteriorated, but the sub is otherwise intact. The top of the conning tower sits at approximately 90 feet. The bottom rests on the sand at around 100 feet. Typically there is a slight to moderate current. The smallish wreck can be circled multiple times in a single dive. You can see the forward torpedo tubes where the bow has cracked, a gun mount and the conning tower.

The wreck attracts schools of baitfish and amberjack, while the hull is home to a variety of smaller fish, sponges and some corals. Rays and turtles are common here, as are sand tiger sharks.

The Ship: Rhone (British Virgin Islands)

Depth: Stern, 35 feet; bow, 80 feet

Viz: 40 to 100 feet

Water Temp: 78 degrees F in winter; 82 degrees F in summer

Dive Tip: Current can vary significantly.

Built in 1865, the iron-hulled steamship was 310 feet long with a beam of 40 feet and could carry 313 passengers; its compound steam engine drove a gigantic three-bladed bronze propeller, only the second of its kind. Rhone was a celebrity — its knack for weathering fierce storms earned it the reputation of being “unsinkable.”

The Sinking

On October 29, 1867, RMS Rhone and RMS Conway were at BVI’s Peter Island when the barometric pressure began to drop. The captains decided to weather the storm, but conditions worsened. Conway transferred its passengers to the larger Rhone, where they were lashed to their bunks for “safety.” As Rhone passed the eye of the storm, it was thrown onto Black Rock Point — the hull was breached, seawater met with super-heated boilers, and the explosion tore the ship in half. Only 23 people — all crew — survived.

The Dive

You’ll need at least two dives to experience Rhone because the two halves are about 100 feet apart. The bow sits in deeper water on its starboard side. The stern and midsection are shallower and can be seen on the same dive. Sights include the huge bronze propeller, which features its own short swim-through, the drive shaft, a group of black-and-white tiles known as “the dance floor,” and the “lucky porthole,” whose glass has remained intact, its metalwork brassy thanks to divers who rub it for luck.