Wide-Angle Solutions

|

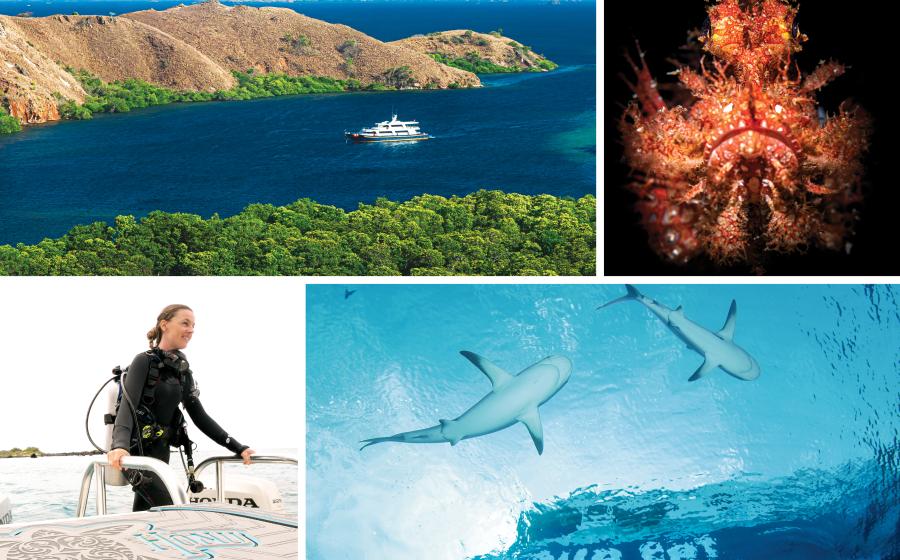

| To capture the big picture--large marine life, divers and schooling fish--a wide-angle lens is a must. |

March 2005

Text and Photography by Stephen Frink

One fundamental challenge of underwater photography is that it takes place in a medium that's about 800 times denser than air. This relatively viscous medium absorbs light and adds a color bias that might be cyan in the Caribbean or green in British Columbia. No matter how clear or what color, seawater is different from air, and to a great extent determines the lenses you might choose for underwater photography.

For example, to photograph a person above water, you could use a normal focal length of 50mm from a distance of eight feet or so, or you could shoot from an extreme distance with a telephoto lens. However, undewater shooters are forced to work in a universe of about five feet. Even five feet of distance means 10 feet of filtration for the strobe to plow through (from the strobe, to the subject, and back to the film/sensor plane), thereby degrading both color and resolution. So, telephotos are out, and even normal lenses won't make the grade. To capture a large subject from this relatively close distance requires a wide-angle lens.

Back in the Day

||

|---|

|  |

|

| A wide-angle lens allows you to force perspective and enhance resolution. |

It was easy in the old days when we had fewer choices. If you wanted to shoot wide-angle on your Nikonos III, you'd use Nikonos's 15mm. The 15mm had great optics, was easy to focus, and with an angle of coverage of 94 degrees (equal to a 20mm on a single lens reflex), this classic lens was ideal for reef scenics, diver portraits and really big fish.

For anyone still shooting a Nikonos, the 15mm lenses from either Nikon or Sea & Sea remain wonderful options. They are very sharp water-contact lenses designed specifically to function through the water interface. In fact, these lenses won't even focus above water. But under water, they are still state-of-the-art and provide an optical ideal that digital systems today try to emulate.

Sea & Sea provided a rather brilliant alternative to the Nikonos with its MotorMarine cameras. The heart of the system was a series of supplementary lenses that could be removed and replaced under water. There were macro kits with framers, close-up lenses and a wide-angle lens that simply mounted over the standard 35mm lens and changed the angle of view to wide. The obvious advantage was that a photographer could be prepared for whatever swam by, from a coral crab to a whale shark. Just slip on the right supplementary optic and shoot. There was even a clever lens caddy so that multiple optical options could be conveniently carried on any given dive. Other manufacturers such as Sealife adopted the same kind of system of supplementary lenses for their housed camera systems.

For those shooting housed cameras, the wide-angle lenses had to be used behind a dome port. If a flat port was used, the angle of view would be compressed and optical problems introduced. The image might be sharp in the center, but at the edges there would likely be spherical aberrations (where objects that are supposed to be round are recorded more as an elongated ellipse) and chromatic aberration (where the colors are separated as if passed through a prism). The domes restore the topside angle of view for the wide angles, but brought their own baggage, most notably the "virtual image."

|

| With cameras like the Sea & Sea DX5000 (with interchangeable accessories), you can shoot topside scenics and then house it for underwater work. |

||

|---|

|  |

|

| Sea & Sea DX5000. Photography by Joseph Byrd. |

There are precise formulas for calculating the location of the virtual image, but for ballpark estimation, we assume that it occurs at twice the diameter of the dome away. So, an eight-inch dome has a virtual image at 16 inches, and the wide-angle lens must be able to focus on the virtual image or it can't focus at all. That was rarely a problem for wide-angle prime lenses that were used with the early housings like the 16mm and 20mm Nikkors, because they focused as close as 12 inches. But the zooms of the day had minimum focus of two feet in many cases, so a diopter (close-up lens) had to be screwed on the front to bring minimum focus near enough to catch the virtual image. It wasn't until fairly recently that Nikon introduced close-focusing zoom lenses like its 17-35mm that could be used behind dome ports without the need of an accessory diopter.

In the film world, the Nikonos retained a pretty strong advantage for wide-angle. SLR viewing was a huge advantage for fish and skittish small subjects; but the convenience, ease of use, and optical quality of the water contact lenses for the Nikonos V and RS made them the go-to systems for any serious wide-angle shooter. However, now that digital rules the seascape, the tools are different, especially in the wide-angle realm.

That Was Then, This Is Now

All the systems mentioned above still do everything they did when they were new, and now you can find them for much lower prices on eBay. But digital imaging brings a whole new set of tools that have to be adapted to the physics of the underwater realm. Both point-and-shoot consumer cameras and high-end digital SLRs have to overcome challenges to shoot wide angle under water.

The Point-and-Shoot Solution

The clever use of supplementary wide-angle lenses is just as practical on a housed consumer digital as it is on a Sea & Sea MotorMarine II. In fact, the Sea & Sea wide-angle lenses can be used on both the Ikelite and Sea & Sea housings so that the camera's close-focusing zooms can be used to capture fish and macro, while the addition of a single accessory lens that mounts to the housing port handles the wide end of the range. Inon likewise makes a variety of wide-angle accessory lenses adaptable to underwater housings from Light and Motion, Canon, Olympus, Fantasea and others. Using these lenses is easy, but typically they have to be attached under water so there are no air bubbles between the front of the port and the back of the wide-angle glass. Alternatively, they can be "burped" while under water (removed and reinstalled to displace any air bubbles).

To shoot wide-angle, some housings use supplementary wide-angle lenses behind a custom dome port. With the right dome and a high-quality accessory lens, this can be a great optical solution, but it doesn't give the shooter the ability to change lenses under water. The photographer would have to shoot wide angle for the entire dive. Not a bad option normally, but frustrating when you find a tiger grouper with its mouth wide open at a cleaning station while neon gobies do their thing. Getting close enough to fill the frame with wide angle would likely disrupt the behavior, so it would be nice to be able to remove the wide lens and shoot from a little greater distance.

The D-SLR Solution

Many of the options that have been available since the first single lens reflex camera was taken under water still work for the modern housed D-SLR, with some caveats. The primary concern is that the angle of coverage of the lens may not be the same because the size of the sensor is not necessarily the same as with 35mm film. With the exception of a few full-frame sensors (Canon EOS1DSMKII and Kodak SLR/N), D-SLR image sensors are usually a bit smaller than 35mm film, typically 13mm or 19mm along the shorter side as compared to film's 24mm. That creates a magnification factor of 1.3 or 1.5. Taking a 1.5 imager as example, a 20mm wide (equivalent to the venerable Nikonos 15mm) behaves like a 30mm lens. So, instead of a true wide angle that's suitable for divers and broad reef scenics, you'd have a moderate wide angle, something good for schooling fish or maybe head-and-shoulder shots of divers. Since you can't just back up farther like you might do topside, this is a huge issue for underwater shooters.

Fortunately, some camera manufacturers have addressed this problem with "digital only" lenses like Nikon's 10.5mm fisheye and 12-24 wide-angle zoom, and Canon now has a 10-22mm wide zoom for its 20D and Digital Rebel cameras. "It was better from our point of view to make lenses fit a smaller imaging chip than to make a larger chip to fit existing lenses," says Nikon's Steve Heiner. Of course, for a housing user, it matters little whether the lens is custom-designed to cover a smaller chip or whether a full-frame chip resides inside the camera body and conventional wide lenses are used. It's still all about finding the sweet spot that combines focus on the virtual image and optimal performance from center to corner.

Photo Gear > Storm Cases

||

|---|

|  |

|

Nine pounds doesn't seem like a lot of weight if you're lifting it in the gym. But when you're trying to meet the 70-pound cap for international travel, nine pounds is an extra camera and a couple of lenses. In other words, a very big deal. That is the difference between the empty weight of the popular Pelican 1620 (30 pounds) and the virtually same-sized Storm 2750 (20.9 pounds). When I traveled to Fiji recently with the Storm case, I found a lot of other features to admire in this extremely robust equipment case.

I got mine in orange, but the cases are also available in black, gray, yellow and olive drab green, in any of 16 different sizes. The latches are significantly different from those on competitive cases; rather than a "snap" clasp, these are a press and pull design. Secure and easy to operate, they offer the advantage of being gentle on the knuckles. Other enhancements include a proprietary "vortex" pressure release valve that automatically responds to pressure differential, a tongue-and-groove waterproof lid, a durable padded handle and oversized wheels. Small details like the interlocking anti-shear teeth, which keeps the lid from shifting during impact, are also handy.

These cases can be ordered with multilayer cubed "pluck-and-pull" foam or padded dividers. With the larger cases, there is a lower compartment that can be customized with movable Velcro dividers, as well as a shallow upper shelf for smaller accessories. I find the lower section perfect for large housings and strobes, while smaller items can be organized in the small compartments above. With all these innovations, Storm Cases clearly carry this category to a new level. Web: www.stormcase.com.

|| |---|

| |

| To capture the big picture--large marine life, divers and schooling fish--a wide-angle lens is a must. |

|

| To capture the big picture--large marine life, divers and schooling fish--a wide-angle lens is a must. |

March 2005

Text and Photography by Stephen Frink

One fundamental challenge of underwater photography is that it takes place in a medium that's about 800 times denser than air. This relatively viscous medium absorbs light and adds a color bias that might be cyan in the Caribbean or green in British Columbia. No matter how clear or what color, seawater is different from air, and to a great extent determines the lenses you might choose for underwater photography.

For example, to photograph a person above water, you could use a normal focal length of 50mm from a distance of eight feet or so, or you could shoot from an extreme distance with a telephoto lens. However, undewater shooters are forced to work in a universe of about five feet. Even five feet of distance means 10 feet of filtration for the strobe to plow through (from the strobe, to the subject, and back to the film/sensor plane), thereby degrading both color and resolution. So, telephotos are out, and even normal lenses won't make the grade. To capture a large subject from this relatively close distance requires a wide-angle lens.

Back in the Day

|| |---|

| |

| A wide-angle lens allows you to force perspective and enhance resolution. |

It was easy in the old days when we had fewer choices. If you wanted to shoot wide-angle on your Nikonos III, you'd use Nikonos's 15mm. The 15mm had great optics, was easy to focus, and with an angle of coverage of 94 degrees (equal to a 20mm on a single lens reflex), this classic lens was ideal for reef scenics, diver portraits and really big fish.

|

| A wide-angle lens allows you to force perspective and enhance resolution. |

It was easy in the old days when we had fewer choices. If you wanted to shoot wide-angle on your Nikonos III, you'd use Nikonos's 15mm. The 15mm had great optics, was easy to focus, and with an angle of coverage of 94 degrees (equal to a 20mm on a single lens reflex), this classic lens was ideal for reef scenics, diver portraits and really big fish.

For anyone still shooting a Nikonos, the 15mm lenses from either Nikon or Sea & Sea remain wonderful options. They are very sharp water-contact lenses designed specifically to function through the water interface. In fact, these lenses won't even focus above water. But under water, they are still state-of-the-art and provide an optical ideal that digital systems today try to emulate.

Sea & Sea provided a rather brilliant alternative to the Nikonos with its MotorMarine cameras. The heart of the system was a series of supplementary lenses that could be removed and replaced under water. There were macro kits with framers, close-up lenses and a wide-angle lens that simply mounted over the standard 35mm lens and changed the angle of view to wide. The obvious advantage was that a photographer could be prepared for whatever swam by, from a coral crab to a whale shark. Just slip on the right supplementary optic and shoot. There was even a clever lens caddy so that multiple optical options could be conveniently carried on any given dive. Other manufacturers such as Sealife adopted the same kind of system of supplementary lenses for their housed camera systems.

For those shooting housed cameras, the wide-angle lenses had to be used behind a dome port. If a flat port was used, the angle of view would be compressed and optical problems introduced. The image might be sharp in the center, but at the edges there would likely be spherical aberrations (where objects that are supposed to be round are recorded more as an elongated ellipse) and chromatic aberration (where the colors are separated as if passed through a prism). The domes restore the topside angle of view for the wide angles, but brought their own baggage, most notably the "virtual image."

|| |---|

| |

| With cameras like the Sea & Sea DX5000 (with interchangeable accessories), you can shoot topside scenics and then house it for underwater work. |

|

| With cameras like the Sea & Sea DX5000 (with interchangeable accessories), you can shoot topside scenics and then house it for underwater work. |

|| |---|

| |

| Sea & Sea DX5000. Photography by Joseph Byrd. |

There are precise formulas for calculating the location of the virtual image, but for ballpark estimation, we assume that it occurs at twice the diameter of the dome away. So, an eight-inch dome has a virtual image at 16 inches, and the wide-angle lens must be able to focus on the virtual image or it can't focus at all. That was rarely a problem for wide-angle prime lenses that were used with the early housings like the 16mm and 20mm Nikkors, because they focused as close as 12 inches. But the zooms of the day had minimum focus of two feet in many cases, so a diopter (close-up lens) had to be screwed on the front to bring minimum focus near enough to catch the virtual image. It wasn't until fairly recently that Nikon introduced close-focusing zoom lenses like its 17-35mm that could be used behind dome ports without the need of an accessory diopter.

|

| Sea & Sea DX5000. Photography by Joseph Byrd. |

There are precise formulas for calculating the location of the virtual image, but for ballpark estimation, we assume that it occurs at twice the diameter of the dome away. So, an eight-inch dome has a virtual image at 16 inches, and the wide-angle lens must be able to focus on the virtual image or it can't focus at all. That was rarely a problem for wide-angle prime lenses that were used with the early housings like the 16mm and 20mm Nikkors, because they focused as close as 12 inches. But the zooms of the day had minimum focus of two feet in many cases, so a diopter (close-up lens) had to be screwed on the front to bring minimum focus near enough to catch the virtual image. It wasn't until fairly recently that Nikon introduced close-focusing zoom lenses like its 17-35mm that could be used behind dome ports without the need of an accessory diopter.

In the film world, the Nikonos retained a pretty strong advantage for wide-angle. SLR viewing was a huge advantage for fish and skittish small subjects; but the convenience, ease of use, and optical quality of the water contact lenses for the Nikonos V and RS made them the go-to systems for any serious wide-angle shooter. However, now that digital rules the seascape, the tools are different, especially in the wide-angle realm.

That Was Then, This Is Now

All the systems mentioned above still do everything they did when they were new, and now you can find them for much lower prices on eBay. But digital imaging brings a whole new set of tools that have to be adapted to the physics of the underwater realm. Both point-and-shoot consumer cameras and high-end digital SLRs have to overcome challenges to shoot wide angle under water.

The Point-and-Shoot Solution

The clever use of supplementary wide-angle lenses is just as practical on a housed consumer digital as it is on a Sea & Sea MotorMarine II. In fact, the Sea & Sea wide-angle lenses can be used on both the Ikelite and Sea & Sea housings so that the camera's close-focusing zooms can be used to capture fish and macro, while the addition of a single accessory lens that mounts to the housing port handles the wide end of the range. Inon likewise makes a variety of wide-angle accessory lenses adaptable to underwater housings from Light and Motion, Canon, Olympus, Fantasea and others. Using these lenses is easy, but typically they have to be attached under water so there are no air bubbles between the front of the port and the back of the wide-angle glass. Alternatively, they can be "burped" while under water (removed and reinstalled to displace any air bubbles).

To shoot wide-angle, some housings use supplementary wide-angle lenses behind a custom dome port. With the right dome and a high-quality accessory lens, this can be a great optical solution, but it doesn't give the shooter the ability to change lenses under water. The photographer would have to shoot wide angle for the entire dive. Not a bad option normally, but frustrating when you find a tiger grouper with its mouth wide open at a cleaning station while neon gobies do their thing. Getting close enough to fill the frame with wide angle would likely disrupt the behavior, so it would be nice to be able to remove the wide lens and shoot from a little greater distance.

The D-SLR Solution

Many of the options that have been available since the first single lens reflex camera was taken under water still work for the modern housed D-SLR, with some caveats. The primary concern is that the angle of coverage of the lens may not be the same because the size of the sensor is not necessarily the same as with 35mm film. With the exception of a few full-frame sensors (Canon EOS1DSMKII and Kodak SLR/N), D-SLR image sensors are usually a bit smaller than 35mm film, typically 13mm or 19mm along the shorter side as compared to film's 24mm. That creates a magnification factor of 1.3 or 1.5. Taking a 1.5 imager as example, a 20mm wide (equivalent to the venerable Nikonos 15mm) behaves like a 30mm lens. So, instead of a true wide angle that's suitable for divers and broad reef scenics, you'd have a moderate wide angle, something good for schooling fish or maybe head-and-shoulder shots of divers. Since you can't just back up farther like you might do topside, this is a huge issue for underwater shooters.

Fortunately, some camera manufacturers have addressed this problem with "digital only" lenses like Nikon's 10.5mm fisheye and 12-24 wide-angle zoom, and Canon now has a 10-22mm wide zoom for its 20D and Digital Rebel cameras. "It was better from our point of view to make lenses fit a smaller imaging chip than to make a larger chip to fit existing lenses," says Nikon's Steve Heiner. Of course, for a housing user, it matters little whether the lens is custom-designed to cover a smaller chip or whether a full-frame chip resides inside the camera body and conventional wide lenses are used. It's still all about finding the sweet spot that combines focus on the virtual image and optimal performance from center to corner.

Photo Gear > Storm Cases

|| |---|

| |

Nine pounds doesn't seem like a lot of weight if you're lifting it in the gym. But when you're trying to meet the 70-pound cap for international travel, nine pounds is an extra camera and a couple of lenses. In other words, a very big deal. That is the difference between the empty weight of the popular Pelican 1620 (30 pounds) and the virtually same-sized Storm 2750 (20.9 pounds). When I traveled to Fiji recently with the Storm case, I found a lot of other features to admire in this extremely robust equipment case.

|

Nine pounds doesn't seem like a lot of weight if you're lifting it in the gym. But when you're trying to meet the 70-pound cap for international travel, nine pounds is an extra camera and a couple of lenses. In other words, a very big deal. That is the difference between the empty weight of the popular Pelican 1620 (30 pounds) and the virtually same-sized Storm 2750 (20.9 pounds). When I traveled to Fiji recently with the Storm case, I found a lot of other features to admire in this extremely robust equipment case.

I got mine in orange, but the cases are also available in black, gray, yellow and olive drab green, in any of 16 different sizes. The latches are significantly different from those on competitive cases; rather than a "snap" clasp, these are a press and pull design. Secure and easy to operate, they offer the advantage of being gentle on the knuckles. Other enhancements include a proprietary "vortex" pressure release valve that automatically responds to pressure differential, a tongue-and-groove waterproof lid, a durable padded handle and oversized wheels. Small details like the interlocking anti-shear teeth, which keeps the lid from shifting during impact, are also handy.

These cases can be ordered with multilayer cubed "pluck-and-pull" foam or padded dividers. With the larger cases, there is a lower compartment that can be customized with movable Velcro dividers, as well as a shallow upper shelf for smaller accessories. I find the lower section perfect for large housings and strobes, while smaller items can be organized in the small compartments above. With all these innovations, Storm Cases clearly carry this category to a new level. Web: www.stormcase.com.